I began my first book on Vietnam (Masters of War) with a poem, Adrian Mitchell’s “To Whom It May Concern”:

You put your bombers in, you put your conscience out.

You take the human being and you twist it all about

So scrub my skin with women

Chain my tongue with whisky

Stuff my nose with garlic

Coat my eyes with butter

Fill my ears with silver

Stick my legs in plaster

Tell me lies about Vietnam.

When written in 1968, Americans were finally realizing and tiring of the lies they had been told about Vietnam. And the point of the poem was that, against that flood of lies, was some kind of truth, one that a majority of Americans began to understand as they opposed the American war on Vietnam.

“Triangulating” (or Teaching?) the War

Now, a half-century later, America’s best-known documentarians and teachers of popular history, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick have produced an 18-hour examination of the war for PBS (a “masterpiece” according to George Will, with sponsorship and promotion from the Koch Brothers, Bank of America, and Pentagon, inter alia) which is getting a huge amount of attention already. Like their documentary on the Civil War, The Vietnam War will surely become a major work of public history and be ingrained in our national consciousness. But what do Burns and Novick do, is it anything new, and what consequences will their work have?

Burns and Novick, in their public relations blitz for the show (which debuted Sunday night, September 17th) have stressed that this documentary is different than the studies of Vietnam that have preceded it because they focused on the people who were involved in the war and especially representatives of the enemy (the “North Vietnamese” in their parlance, not the “revolutionaries” or “the NLF”). Their goal was to “triangulate” the telling of the war—speak to people from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and the United States. Their main purpose is to “honor the courage, heroism and sacrifice of those who served,” and “we have tried to do this by listening to their stories.” They add that they conveyed the tragedy of the war through “good storytelling.”

In addition to telling the stories of Americans who fought in Vietnam, Burns and Novick talk to partisans from the enemy, who talk of battles and tactics and their simultaneous respect and hatred of the Americans they fought. In fact, the documentarians seem to suggest that the Vietnamese were unaware of much about the war until educated by Americans. In Vietnam, Novick was surprised to see “a willingness, an openness” to talk about the war in a way “they never speak about it in Vietnam, which is the human story . . . . The war there is sort of a grand sort of victorious narrative without people in it.” And the people to whom Novick spoke “want the next generation to know how terrible it was, how difficult it was.” (Emphases mine).

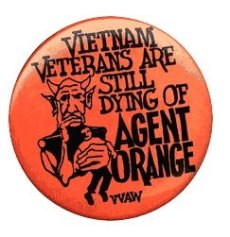

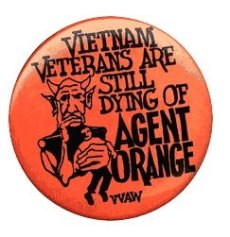

I haven’t been to Vietnam, so maybe they’re right. But I’m pretty certain the Vietnamese talk about the war and know how terrible and difficult it was . . . I’ve talked to a lot of Vietnamese about the war, in depth . . . the war fought for decades in their country. They lost 2-3 million people in the American phase of their long struggle, which means that virtually every family had an immediate member die. There are cemeteries and memorials all over, constant reminders of the war. There are museums to honor battles fought and soldiers and civilians killed. There is a museum dedicated to the dead at My Lai. A close friend who spent 3 months traveling in the area told me that remembering the war in general and its victims is “one of the most significant parts of their identity, more so than here.” There are tributes to the dead. There is a replica of the Washington D.C. Vietnam “Wall.” And if they’re somehow not aware of how terrible the war was, the continued loss of life, perhaps as many as 50,000 people after hostilities ended, from unexploded bombs, and the continued impact of Agent Orange in high cancer rates and countless deformed babies, would help them remember. Did the Vietnamese really need two Americans, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, to finally teach them about the bloodshed and devastation their own land suffered because of the Americans?

I haven’t been to Vietnam, so maybe they’re right. But I’m pretty certain the Vietnamese talk about the war and know how terrible and difficult it was . . . I’ve talked to a lot of Vietnamese about the war, in depth . . . the war fought for decades in their country. They lost 2-3 million people in the American phase of their long struggle, which means that virtually every family had an immediate member die. There are cemeteries and memorials all over, constant reminders of the war. There are museums to honor battles fought and soldiers and civilians killed. There is a museum dedicated to the dead at My Lai. A close friend who spent 3 months traveling in the area told me that remembering the war in general and its victims is “one of the most significant parts of their identity, more so than here.” There are tributes to the dead. There is a replica of the Washington D.C. Vietnam “Wall.” And if they’re somehow not aware of how terrible the war was, the continued loss of life, perhaps as many as 50,000 people after hostilities ended, from unexploded bombs, and the continued impact of Agent Orange in high cancer rates and countless deformed babies, would help them remember. Did the Vietnamese really need two Americans, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, to finally teach them about the bloodshed and devastation their own land suffered because of the Americans?

And therein lies the core flaw of the entire project—it’s a series of stories, but not really a history of the war. That’s the Burns-Novick trademark and it’s worked for a long time, making them famous and I suspect wealthy. But it substitutes vignettes for ideas, personal anecdotes for larger structural factors, bathos for analysis. And it ends up providing a misguided view of the war, one that has politically conservative consequences (ironic because Burns himself is openly liberal) by shifting attention away from the historical, material reasons for American intervention and focusing on 79 people interviewed who were directly involved in Vietnam. Instead of an exposé of aggressive militarism, they give us sentimental stories of survival and perseverance.

Burns and Novick, despite their claims of originality, provide a pretty boilerplate liberal examination of the war. It “was begun in good faith, by decent people.” The people of South Vietnam created a state, the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), which was invaded by “North Vietnam” and precipitated the war because of the American mission to prevent Communists from taking over “free” countries. After the partition of Vietnam at Geneva, the conflict became a “civil war” in which the U.S. became involved to save the “free” southern half of Vietnam according to Cold War logic. Americans made anguished decisions to invade and then escalate the war, they kept blundering further along and then couldn’t get out, there were decisive battles at places like Ap Bac and Ia Drang, Americans turned on the war, it was a tragedy, there are only victims, and so on . . . It’s not a bad history, but in no way original and in its pursuit of “all sides” it creates a false equivalency. The intervention into Vietnam was a war crime, and PBS isn’t going to fund a documentary saying that, and Burns and Novick don’t go beyond the liberal consensus to think about it.

More Reconciliation and Healing

Burns and Novick talk a lot about reconciliation and healing, sort of a Vietnam War version of Dr. Phil and Oprah. “For more than a generation, instead of forging a path to reconciliation, we have allowed the wounds the war inflicted on our nation, our politics and our families to fester,” they claim. “ . . . alienation, resentment and cynicism; mistrust of our government and one another; breakdown of civil discourse and civic institutions . . . so many of these seeds were sown during the Vietnam War.” The war wracked American society, pitting generation against generation, even family against family. These are troubling issues to be sure, and Burns and Novick seem to easily pin them on Vietnam. But their explanation is facile and self-serving.

Is America really still divided over Vietnam the way it was in, say, 1968, when Walter Cronkite stunned the White House and Main Street by essentially declaring that the war was unwinnable? Since then, and once the war ended, the U.S. and Vietnam have erased much of the acrimony. Americans withheld reparations aid and prevented Hanoi from getting reconstruction funds from lending agencies, so the Vietnamese began a policy of economic restructuring that eventually led to this “Socialist Republic” joining the WTO, and becoming a major trading partner.

In 2000, trade between the U.S. and Hanoi amounted to a bit over a billion dollars ($821 million in imports). After that, commerce increased significantly, to $15.7 billion in 2008 ($12.9 billion imports), $24.9 billion in 2012 ($20.6 billion imports), and in 2015 and 2016, $45 and $52 billion ($38 and $42 billion imports). Most recently, the U.S. has also included Vietnam in the stalled-Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), its trade alliance for Asia and the Pacific. In addition to that, American tourists are well-received in Vietnam and only Chinese, South Koreans, and Japanese visit more frequently, and among Americans, veterans of the Vietnam War comprise a large number of tourists, often as part of programs to bring together U.S. and Vietnamese soldiers. Inside the U.S., there are hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese-Americans well-integrated into American society,  economy, and politics.

economy, and politics.

Reconciliation and healing are always worthwhile and necessary goals, but that process has been well in place long before Burns and Novick arrived. The promotional material for the series boasts that they “unbury the secrets of the Vietnam War.” They also stress they want to let Americans know about Vietnam. But don’t we know a lot already? Many scholars from the U.S., Vietnam, and elsewhere have studied the Vietnam War and Vietnamese history in intricate details which are not a “secret” to us. And we know and understand a lot more about the Vietnam war than Burns and Novick realize, or are willing to admit.

Vietnam was the “living room war.” There has been a huge number of books and novels published about the war. Documentary series have been widely-watched and praised long before the new Burns effort, like “The Ten Thousand Day War,” a Canadian series; “Vietnam: A Television History,” with its companion book by Stanley Karnow; or “Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam,” “Sir! No Sir!,” “In The Year of the Pig,” or the Oscar-winning “Hearts and Minds,” and of course movies such as Platoon, The Deer Hunter, Coming Home, Apocalypse Now, Go Tell the Spartans, and television series China Beach, and Tour of Duty have been widely viewed and popular. Burns and Novick are hardly entering into unknown historical terrain here, their claims notwithstanding.

Vietnam was the “living room war.” There has been a huge number of books and novels published about the war. Documentary series have been widely-watched and praised long before the new Burns effort, like “The Ten Thousand Day War,” a Canadian series; “Vietnam: A Television History,” with its companion book by Stanley Karnow; or “Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam,” “Sir! No Sir!,” “In The Year of the Pig,” or the Oscar-winning “Hearts and Minds,” and of course movies such as Platoon, The Deer Hunter, Coming Home, Apocalypse Now, Go Tell the Spartans, and television series China Beach, and Tour of Duty have been widely viewed and popular. Burns and Novick are hardly entering into unknown historical terrain here, their claims notwithstanding.

Breeding Cynicism

Burns and Novick are also disturbed by the “sea change” in the way Americans view the presidency, how Vietnam eroded faith in our leaders, sowed the seeds for a more-divided society, and how the war and dissent “sort of metastasized into terrible cynicism under Nixon that we cannot trust our presidents, that they don’t tell us the truth, that they are not doing the right thing, and that, you know, just sort of a pox on both their houses.” This liberal myth of a virtuous “American-ness” gone wrong is a hallmark of a Burns-Novick joint, and here again it shows its fangs.

To begin, Burns and Novick are more than a bit off on this point. Americans have long distrusted their leaders, as the Civil War (something about which they should know a little) would attest. Or the election of 1896, when plutocrats gave William McKinley a $10 million war chest to beat back the spectre of Populism . . . or the hatred thrown at Herbert Hoover in 1929 when the economy crashed . . . or the ugly virulence with which political enemies went after FDR for the New Deal . . . or the blunt attacks on Truman for knowing little and being an empty suit when he took over after Roosevelt.

To begin, Burns and Novick are more than a bit off on this point. Americans have long distrusted their leaders, as the Civil War (something about which they should know a little) would attest. Or the election of 1896, when plutocrats gave William McKinley a $10 million war chest to beat back the spectre of Populism . . . or the hatred thrown at Herbert Hoover in 1929 when the economy crashed . . . or the ugly virulence with which political enemies went after FDR for the New Deal . . . or the blunt attacks on Truman for knowing little and being an empty suit when he took over after Roosevelt.

They also suggest that the decisions made by American presidents to go to war were based on “domestic political considerations,” a “polite way” of saying “Will I get re-elected?” I’ve studied Vietnam for a long time and have been as critical of the U.S. administrations which began and fought the Vietnam War as anyone,* but I’ve never seen any suggestion that Vietnam was crucial to one’s election prospects. There were certainly questions raised about American “credibility,” meaning the need to have one’s allies trust you and enemies fear you. These concerns, however, were not simply crude calculations about election prospects, and any concern on behalf of Truman or Eisenhower that Vietnam had even a subatomic role in their campaigns is lacking. There are historians who claim that JFK would have withdrawn from Vietnam after the 1964 election, but almost all scholars have debunked that (see especially Thomas Paterson, ed., Kennedy’s Quest for Victory). In 1964, Vietnam was used to appease doves, invoked only to show that LBJ would not recklessly get involved in a war there, unlike his hawkish opponent Barry Goldwater. And in 1968 and 1972 the war had a big impact on the election, but because Americans were tiring and pessimistic about it not threatening to punish politicians for “losing” there. Suggesting that intervention and escalation was required by domestic politics does not rest on a solid foundation.

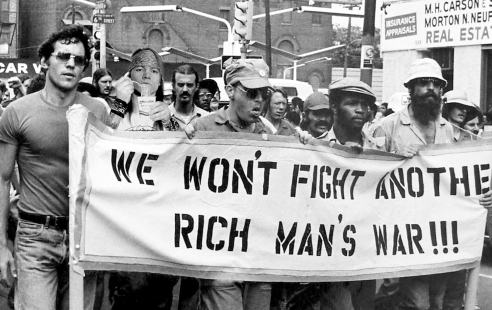

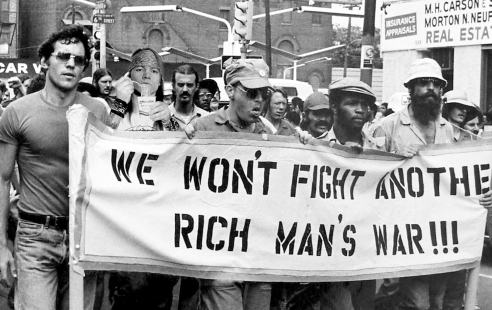

But more than that, cynicism and a lack of deference would be seen by many of us as positive outcomes of the Vietnam era. The “trust” Americans had in their government included acceptance, sometimes tacit and often overt, in conditions like racial apartheid, a conformist culture, fixed gender roles, an exaggerated fear of communism that destroyed people’s lives, a terrifying and economically devastating Cold War. If Vietnam did indeed motivate Americans to question authority and assume they were being told lies, then that can be placed in the assets ledger.

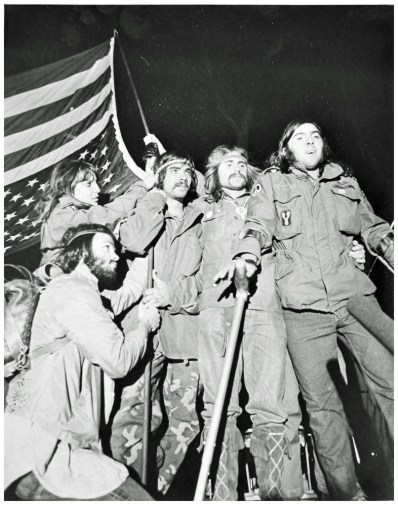

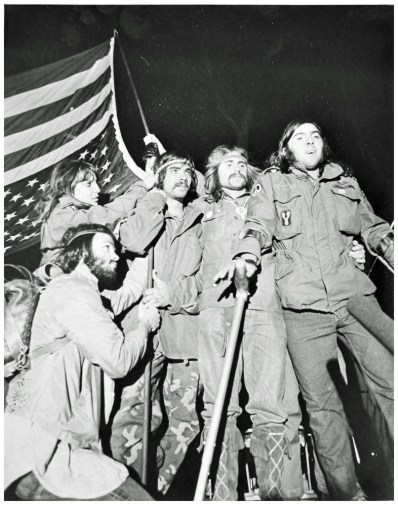

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Many Truths of Vietnam

To Burns and Novick, “there is no simple or single truth to be extracted from the Vietnam War. Many questions remain unanswerable.” However, “with open minds and open hearts,” (I wonder if they used that phrase ironically) “perhaps we can stop fighting over how the war should be remembered and focus instead on what it can teach us about courage, patriotism, resilience, forgiveness and, ultimately, reconciliation.” Again, they talk of reconciliation more than Dr. Phil, but simply are unaware that the “fighting over how the war should be remembered” is a political issue. While their goal of “triangulation”—telling everyone’s story—isn’t a bad idea, it is a distraction from the overwhelming reason for the war: American aggression.

If there is indeed a “Vietnam Syndrome,” making Americans more reluctant to intervene abroad (and I’ve always questioned the very existence of such a reticence, but that’s for another day), or whether the “lesson” of Vietnam is to strike early and often, the historical analysis is inherently a political analysis. The lessons of Vietnam can be applied, say, to Syria or North Korea today, but both by partisans of diplomacy and “hands off,” or by advocates of intervention and “bombs away.” I don’t think Burns has ever realized how immanently political the study of history is, because he and Novick aim to tell the stories of people involved in the war, and there’s no doubt oral history is a vital component of understanding the past, but they do not provide a comprehensive and coherent analysis of the war in the way so many previous books and documentaries have.

To be sure, Burns and Novick certainly do tell a truth through their interviews with Vietnamese and Americans who had a direct experience of the war. And if their documentary was titled “Stories of People Who Were in Vietnam During the War”—which would have been compelling and important—there would be little to complain about.

But it’s being advertised as a history of the war, and therein lies the biggest problem. Soldiers’ narratives provide moving ideas and images of the human cost of battle, but they don’t answer the larger questions about why empires attack smaller nations and virtually blow them back to the Stone Age. There are certain elements of the historical episode known as The Vietnam War (or, in Vietnam, “The American War”) that are absolutely essential to understanding the U.S. role in Vietnam from 1945 to 1975, including (and this is a brief listing):

- The U.S. had no singular interest in Vietnam itself, but put a huge priority on establishing global economic hegemony and, therein, on creating or restoring capitalism in Asia, with Japan (and China before 10/1/1949) as the linchpin and American partner. In that context, a small country like Vietnam was critical to provide an outlet for Japanese capitalism—via markets, consumers, raw materials, and investment. (On this point, see especially Andrew Rotter, The Path to Vietnam, also Lloyd Gardner, Approaching Vietnam, and William Borden, The Pacific Alliance).

- The U.S. rejected overtures from Ho Chi Minh to develop a modus vivendi and instead sanctioned a return by the French Empire because appeasing Paris and maintaining its role as a Cold War ally in Europe was far more important than a small and unimportant place like Vietnam. It also “invented” a country below the 17th Parallel, put a client, Ngo Dinh Diem, in power, and prevented elections to unify Vietnam from occurring, tolerated and bankrolled the police state that Diem and his family ran, and increasingly sent money, advisors, and weapons to Vietnam to destroy a popular liberation movement.

- In November 1963, as Diem and his brother Nhu, amid a crisis over repression of Buddhists, were talking to Hanoi about a negotiated, neutralist settlement, the U.S. sanctioned a coup which left the Ngo brothers dead. From that point on, the U.S. facilitated the ouster of several other regimes. From the Diem coup until February 1965, Vietnam had a dozen governments, leaving an exasperated LBJ to finally demand “no more coup shit.” Throughout this time, the politburo in Hanoi was reluctant to act too aggressively in the south for fear of provoking American intervention; it would rather have the RVN implode.

- The RVN in fact was imploding, as the Americans recognized, and so the U.S. increasingly took over the war, sending billions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of soldiers, and dropping 6 million tons of bombs on Vietnam, killing 2-3 million Vietnamese and creating 15 million refugees. They created “free fire zones” and used “search and destroy” tactics and even assassination programs like Operation Phoenix. Americans indiscriminately bombed not just the enemy in the north but the villages of its ally in the south. And American forces committed atrocities at My Lai and elsewhere as a tactic of war (see Nick Turse, Kill Anything That Moves) Hence the “war crime” designation . . .

- Despite this immense war, the RVN never had a legitimate claim to the loyalty of the Vietnamese and the war, despite huge numbers of enemies killed, never went well for the U.S. By the 1968 Tet Offensive, it was clear that the U.S. had no successful path out of Vietnam, and the war was destroying the global economy.

- In the aftermath of Tet, it was clear that the U.S. had to get out of Vietnam, but before it left, it intensified the air war against the north and expanded the war into Laos and Cambodia, killing hundreds of thousands more and unleashing the Khmer Rouge.

- By the time the U.S. finally left Vietnam in 1973, the RVN was in shambles, the U.S. had lost much/most of its global credibility, the economic consequences were significant, 58,000 Americans were dead, and Vietnam was physically devastated.

- In the aftermath of the war, the U.S. refused to pay reparations to Vietnam and prevented international agencies like the IMF or World Bank to offer reconstruction aid.

True War Stories

Ultimately, the Burns and Novick series ratifies the liberal ideology which brought on the war and the idea of American exceptionalism which makes such toxic endeavors possible. Sure, the U.S. made mistakes, but they were honestly made by decent men. And the North Vietnamese have their own ghosts to confront. The Vietnamese, Burns and Novick tell us, “have begun to ask themselves whether the war was necessary, whether some other way might have been found to reunite their country.” Well, there was actually a way to reunite their country and in May 1954 at Geneva, the U.S. and other powers denied them that reunification, put the Kato Kaelin of Indochina in power, poured blood and money into an autocratic regime, and waged the largest conflict outside of the two world wars.

The war was necessary because the U.S. made it necessary—the politburo in Hanoi and the NLF in the south would gladly have taken control of Vietnam without getting blown up and killed in apocalyptic numbers by American weapons. Equivalency and objectivity are the tools of liberal apologetics, and Burns and Novick have always used them well to make Americans (and Americans below the Mason-Dixon Line) feel good about themselves. Instead of examining American aggression, they ruminate on Vietnamese irredentism. Love them, they’re liberals.

What Burns and Novick are really looking for is a shot at redemption, for all the decent men who went to war and wiped out large swaths of Vietnam. The war resulted from blunders and mistakes, it tragically divided a country that . . . should be conformist and static? Even in those dark times, like the protests of antiwar activists, there is virtue, as a North Vietnamese soldier told Burns and Novick that America’s opposition to the war was a sign of strength because it showed that the U.S. was a free and democratic society where dissent was okay . . . and apparently so was invading and destroying other countries.

Among the partisans interviewed and featured were Mai Elliott, Bao Ninh, and Tim O’Brien, each of who has also written eloquently about the war. And it seems fitting to end this rumination, one that I began with a poem about the lies of Vietnam, with the powerful words of O’Brien, whom I believe is the greatest novelist of the Vietnam War. In The Things They Carried, he has a short story titled “How To Tell a True War Story,” which concludes

“A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie. There is no rectitude whatsoever. There is no virtue. As a first rule of thumb, therefore, you can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising allegiance to obscenity and evil.”

Burns’s and Novick’s war stories don’t teach us the history of Vietnam, and leave us with myth, contrived patriotism, and nostalgia. Their series surely doesn’t try to convince us that the Vietnam War was a good idea, but nor does it provide a basis for examining the war to help us going forward as “decent men” are ready to “blunder” into wars in the Middle East, the Korean peninsula, or elsewhere. When we’re done, we’re hypnotized by Burns’ heroic war stories instead of being encouraged to take heed of O’Brien’s real ones.