In an ideal world, there would be no pets and certainly no pet industry. Domestication of animals, beginning with domestication of the wolf 12,000 years ago, was part of the process of alienation of humans from nature, and our subsequent and ongoing attempt to control it. Enslavement of animals preceded alienation and subsequent subjugation of humans by other humans, that is, the rise of the class society about 10,000 years ago. The capitalist system has commodified animals on massive scale. The pet industry is organized to make profit for an ever-larger market for pets.

Dog breeding industries in Missouri produce and sell one third of the puppies in the U.S. market for dogs. The Proposition B on ballot in Missouri is an attempt by the Humane Society and its allies to regulate the worse offenses of this industry in Missouri. If successful, it will impact animal welfare positively throughout the United States. It should be supported.

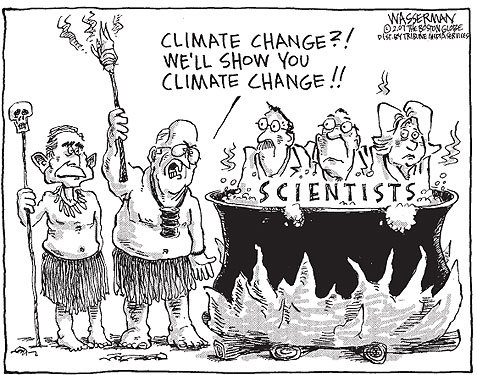

Opponents "describe Proposition B as a proxy battle in the Humane Society’s larger war to end pet ownership, ban hunting and institute vegetarianism throughout the United States

The New York Times article below describes the electoral fight surrounding Proposition B.

* * *

By A. G. Sulzberger and Malcolm Gay, The New York Times, October 30, 2010

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — This is an agricultural state, home to more than 100,000 farms and exporter of an outsize share of the nation’s yearly haul of beef, pork, milk and soybeans. But this year, attention has focused on another local commodity: puppies.

More than one of every three dogs sold in pet stores nationwide come from Missouri, whose breeders produce hundreds of thousands of dogs — from poodles to pit bulls — each year, according to one estimate. That distinction has made this state the target of a well-financed ballot referendum to place tougher regulations on businesses that raise and sell dogs.

The effort pits animal rights groups, led by the Humane Society of the United States, which compiled the estimate, against agricultural interests — old foes who have recently done battle in many states over the welfare of farm animals. Animal rights groups have won a number of protections for animals, as those who make their living selling livestock complain that they are being regulated out of business.

“I am an American; I have a right to raise dogs,” said Joe Overlease, president of the Professional Kennel Club of Missouri, who owns a large breeding operation of cocker spaniels in southern Missouri that was cited by the state this year for overcrowding and inadequate shelter. “I have a right to bark at the moon if I want.”

The Missouri ballot measure, known as Proposition B, would limit the size of dog breeding operations and establish minimum quality of life standards, including requiring additional space, access to the outdoors and periods of rest for females between litters. It would not increase the number of inspectors, currently 12 for the 1,450 licensed breeders statewide. Similar laws have been adopted by 15 states in the last three years, according to the Humane Society, and a recent Mason-Dixon poll showed wide support.

The campaign in support of the proposition has blanketed the state with advertisements against “puppy mills,” the label critics prefer, featuring grainy video images of law enforcement raids on breeding facilities where frail and listless dogs live cramped in wire cages piled with excrement.

“We’ve seen extremely poor overall health because of puppy mill owners putting profit above the health of their breeding stock,” said Kathy Warnick, president of the Humane Society of Missouri, which often assists on the raids.

But leaders of the livestock industry have worked to turn the vote into a referendum on the Humane Society, a nonprofit group based in Washington that has spent more than $2 million in support of the initiative. Outgunned financially, opponents describe Proposition B as a proxy battle in the Humane Society’s larger war to end pet ownership, ban hunting and institute vegetarianism throughout the United States — charges the Humane Society calls ridiculous.

“This is just a first step,” said Charles E. Kruse, president of the Missouri Farm Bureau, echoing the sentiment of many of his members. “It’s pretty clear their ultimate desire is to eliminate the livestock industry in the United States.”

In recent years, the Humane Society has scored several significant victories in its campaign to limit the use of factory farming techniques with more conventional livestock like cattle, pigs and chickens — winning a California ballot initiative in 2008 to increase the size of animal cages and, last summer, wresting similar concessions from producers in Ohio.

The group has also taken aim at some forms of hunting, including campaigning for a ballot measure in North Dakota that would prohibit big game hunting in fenced enclosures.

But Michael Markarian, chief operating officer of the Humane Society, said the Missouri effort was unrelated to the others. “We have concerns with factory farming, and we’ve worked to make it more humane,” he said. “This is a separate matter related only to dogs. And most people don’t think that dogs should be treated like livestock.”

Opponents, like the State Veterinary Medical Association, say Missouri, unlike many states, already has a robust set of laws to protect its breeding dog population, adding that the bulk of problems occur with unlicensed breeders. But Humane Society leaders say they decided to push for greater changes here because Missouri remains the hub of the industry and because legislative efforts have repeatedly failed.

Over the past 10 years, three state audits have criticized the state’s failure to regulate dog breeders adequately, and a recent study by the state’s Better Business Bureau warned that without strict enforcement, breeders, “with seeming impunity, will continue to send sick puppies to be purchased by unwary consumers.”

Nonetheless, most breeders say they take animal welfare into account.

Dave Miller, a 71-year-old cattle rancher, began raising Newfoundlands and other dogs seven years ago because, he says, at his age dogs are easier to handle. He sells about a hundred puppies a year, and he rails against the proposed changes, saying that he spent $180,000 building spacious kennels to meet state and federal requirements.

“It’s going to cause a lot of pain and grief for people who have invested their lives in a business,” Mr. Miller said.