Keep It In The Ground

An alternative vision for petroleum emerges in Ecuador. But will Big Oil win the day?

By Elissa Dennis

The photos accompanying this article were taken by documentary photographers Ben Speck and Karin Ananiassen in Yasuní, Ecuador, March-April 2010, and are part of their series

Black Gold | Precious Green. More photos can be found at

anecdotephotos.com. © Anecdote Photos.

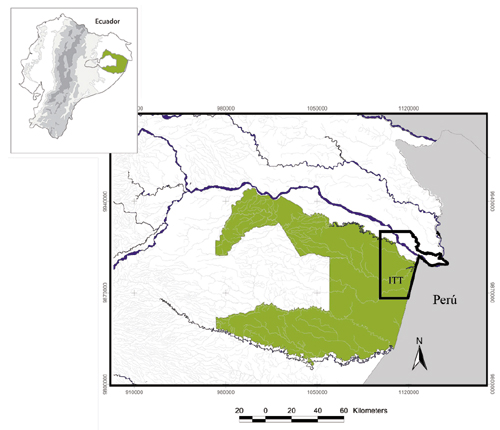

Map of Yasuní: ©

Finding Species, Inc..

In the far eastern reaches of Ecuador, in the Amazon basin rain forest, lies a land of incredible beauty and biological diversity. More than 2,200 varieties of trees reach for the sky, providing a habitat for more species of birds, bats, insects, frogs, and fish than can be found almost anywhere else in the world. Indigenous Waorani people have made the land their home for millennia, including the last two tribes living in voluntary isolation in the country. The land was established as Yasuní National Park in 1979, and recognized as a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve in 1989.

Underneath this landscape lies a different type of natural resource: petroleum. Since 1972, oil has been Ecuador’s primary export, representing 57% of the country’s exports in 2008; oil revenues comprised on average 26% of the government’s revenue between 2000 and 2007. More than 1.1 billion barrels of heavy crude oil have been extracted from Yasuní, about one quarter of the nation’s production to date.

Davo Enomenga of the Waorani tribe in Yasuní, Ecuador. The Waorani hold legal rights to their land, but oil companies have been known to buy off communities with small gifts. Davo Enomenga controls a makeshift checkpoint where he keeps a traditional spear and a shotgun close at hand and demands gifts from anyone crossing his territory to reach oil.

At this economic, environmental, and political intersection lie two distinct visions for Yasuní’s, and Ecuador’s, next 25 years. Petroecuador, the state-owned oil company, has concluded that 846 million barrels of oil could be extracted from proven reserves at the Ishpingo, Tambococha, and Tiputini (ITT) wells in an approximately 200,000-hectare area covering about 20% of the parkland. Extracting this petroleum, either alone or in partnership with interested oil companies in Brazil, Venezuela, or China, would generate approximately $7 billion, primarily in the first 13 years of extraction and continuing with declining productivity for another 12 years.

The alternative vision is the simple but profound choice to leave the oil in the ground. Environmentalists and indigenous communities have been organizing for years to restrict drilling in Yasuní. But the vision became much more real when President Rafael Correa presented a challenge to the world community at a September 24, 2007 meeting of the United Nations General Assembly: If governments, companies, international organizations, and individuals pledge a total of $350 million per year for 10 years, equal to half of the forgone revenues from ITT, then Ecuador will chip in the other half and keep the oil underground indefinitely, as this nation’s contribution to halting global climate change.

The Yasuní-ITT Initiative would preserve the fragile environment, leave the voluntarily isolated tribes in peace, and prevent the emission of an estimated 407 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This “big idea from a small country” has even broader implications, as Alberto Acosta, former Energy Minister and one of the architects of the proposal, notes in his new book, La Maldición de la Abundancia (The Curse of Abundance). The Initiative is a “punto de ruptura,” he writes, a turning point in environmental history which “questions the logic of extractive (exporter of raw material) development,” while introducing the possibility of global “sumak kawsay,” the indigenous Kichwa concept of “good living” in harmony with nature.

Sumak kawsay is the underlying tenet of the country’s 2008 Constitution, which guarantees rights for indigenous tribes and for “Mother Earth.” The Constitution was overwhelmingly supported in a national referendum, but putting the document’s principles into action has been a bigger challenge. While Correa draws praise for his progressive social programs, for example in education and health care, the University of Illinois-trained economist is criticized for not yet having wrested control of the nation’s economy from a deep-rooted powerful elite bearing different ideas about the meaning of “good living.” Within this political and economic discord lies the fate of the Yasuni Initiative.

An Abundance of Oil

Ecuador, like much of Latin America, has long been an exporter of raw materials: cacao in the 19th century, bananas in the 20th century, and now petroleum. Shell discovered the heavy, viscous oil of Ecuador’s Amazon basin in 1948. In the 1950s, a series of controversial encounters began between the native Waorani people and U.S. missionaries from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL). With SIL assistance, Waorani were corralled into a 16,000-hectare “protectorate” in the late 1960s, and many went to work for the oil companies who were furiously drilling through much of the tribe’s homeland.

Manuel Alvarado and Carmen Vargas. Tiputini is one of the three oil fields ready to be exploited should the ITT initiative fail. The tap from the test drilling is planted in the Alvarado family’s backyard, and is oozing crude oil, contaminating their soil and groundwater.

The nation dove into the oil boom of the 1970s, investing in infrastructure and building up external debt. When oil prices plummeted in the 1980s while interest rates on that debt ballooned, Ecuador was trapped in the debt crisis that affected much of the region. Thus began what Correa calls “the long night of neoliberalism”: IMF-mandated privatizations of utilities and mining sectors, with a concomitant decline of revenues from the nation’s natural resources to the Ecuadorian people. By 1986, all of the nation’s petroleum revenues were going to pay external debt.

After another decade of IMF-driven privatizations, oil price drops, earthquakes, and other natural disasters, the Ecuadorian economy fell into total collapse, leading to the 2000 dollarization. Since then, more than one million Ecuadorians have left the country, mostly for the United States and Spain, and remittances from 2.5 million Ecuadorians living in the exterior, estimated at $4 billion in 2008, have become the nation’s second highest source of income.

Close to 40 years of oil production has failed to improve the living standards of the majority of Ecuadorians. “Petroleum has not helped this country,” notes Ana Cecilia Salazar, director of the Department of Social Sciences in the College of Economics of the University of Cuenca. “It has been corrupt. It has not diminished poverty. It has not industrialized this country. It has just made a few people rich.”

Currently 38% of the population lives in poverty, with 13% in extreme poverty. The nation’s per capita income growth between 1982 and 2007 was only 0.7% per year. And although the unemployment rate of 10% may seem moderate, an estimated 53% of the population is considered “underemployed.”

Petroleum extraction has brought significant environmental damage. Each year 198,000 hectares of land in the Amazon are deforested for oil production. A verdict is expected this year in an Ecuadorian court in the 17-year-old class action suit brought by 30,000 victims of Texaco/Chevron’s drilling operations in the area northwest of Yasuní between 1964 and 1990. The unprecedented $27 billion lawsuit alleges that thousands of cancers and other health problems were caused by Texaco’s use of outdated and dangerous practices, including the dumping of 18 billion gallons of toxic wastewater into local water supplies.

Regardless of its economic or environmental impacts, the oil is running out. With 4.16 billion barrels in proven reserves nationwide, and another half billion “probable” barrels, best-case projections, including the discovery of new reserves, indicate the nation will stop exporting oil within 28 years, and stop producing oil within 35 years.

“At this moment we have an opportunity to rethink the extractive economy that for many years has constrained the economy and politics in the country,” says Esperanza Martinez, a biologist, environmental activist, and author of the book Yasuní: El tortuoso camino de Kioto a Quito (Yasuní: The Tortuous Road from Kyoto to Quito). “This proposal intends to change the terms of the North-South relationship in climate change negotiations.”

Collecting on Ecological Debt

The Initiative fits into the emerging idea of “climate debt.” The North’s voracious energy consumption in the past has destroyed natural resources in the South; the South is currently bearing the brunt of global warming effects like floods and drought; and the South needs to adapt expensive new energy technology for the future instead of industrializing with the cheap fossil fuels that built the North. Bolivian president Evo Morales proposed at the Copenhagen climate talks last December that developed nations pay 1% of GDP, totaling $700 billion/year, into a compensation fund that poor nations could use to adapt their energy systems.

“Clearly in the future, it will not be possible to extract all the petroleum in the world because that would create a very serious world problem, so we need to create measures of compensation to pay the ecological debt to the countries,” says Malki Sáenz, formerly Coordinator of the Yasuní-ITT Initiative within the Ministry of Foreign Relations. The Initiative “is a way to show the international community that real compensation mechanisms exist for not extracting petroleum.”

Indigenous and environmental movements in Latin America and Africa are raising possibilities of leaving oil in the ground elsewhere. But the Yasuní-ITT proposal is the furthest along in detail, government sponsorship, and ongoing negotiations. The Initiative proposes that governments, international institutions, civil associations, companies, and individuals contribute to a fund administered through an international organization such as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Contributions could include swaps of Ecuador’s external debt, as well as resources generated from emissions auctions in the European Union and carbon emission taxes such as those implemented in Sweden and Slovakia.

Contributors of at least $10,000 would receive a Yasuní Guarantee Certificate (CGY), redeemable only in the event that a future government decides to extract the oil. The total dollar value of the CGYs issued would equal the calculated value of the 407 million metric tons of non-emitted carbon dioxide.

The money would be invested in fixed income shares of renewable energy projects with a guaranteed yield, such as hydroelectric, geothermal, wind, and solar power, thus helping to reduce the country’s dependence on fossil fuels. The interest payments generated by these investments would be designated for: 1) conservation projects, preventing deforestation of almost 10 million hectares in 40 protected areas covering 38% of Ecuador’s territory; 2) reforestation and natural regeneration projects on another one million hectares of forest land; 3) national energy efficiency improvements; and 4) education, health, employment, and training programs in sustainable activities like ecotourism and agro forestry in the affected areas. The first three activities could prevent an additional 820 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions, tripling the Initiative’s effectiveness.

Government Waffling

These nationwide conservation efforts, as well as the proposal’s mention of “monitoring” throughout Yasuní and possibly shutting down existing oil production, are particularly disconcerting to Ecuadorian and international oil and wood interests. Many speculate that political pressure from these economic powerhouses was behind a major blow to the Initiative this past January, when Correa, in one of his regular Saturday radio broadcasts, suddenly blasted the negotiations as “shameful,” and a threat to the nation’s “sovereignty” and “dignity.” He threatened that if the full package of international commitments is not in place by this June, he would begin extracting oil from ITT.

A Waorani woman with baby in Yawepare. Some Waorani are disillusioned with the oil industry’s ability to lift people out of poverty, fear environmental effects, and wish to profit from sustainable tourism. Others hope the oil industry will bring sorely needed jobs and money.

Correa’s comments spurred the resignations of four critical members of the negotiating commission, including Chancellor Fander Falconí, a longtime ally in Correa’s PAIS party, and Roque Sevilla, an ecologist, businessman, and ex-Mayor of Quito whom Correa had picked to lead the commission. Ecuador’s Ambassador to the UN Francisco Carrion also resigned from the commission, as did World Wildlife Fund president Yolanda Kakabadse.

Correa has been clear from the outset that the government has a Plan B, to extract the oil, and that the non-extraction “first option” is contingent on the mandated monetary commitments. But oddly his outburst came as the negotiating team’s efforts were bearing fruit. Sevilla told the press in January of commitments in various stages of approval from Germany, Spain, Belgium, France, and Switzerland, totaling at least $1.5 billion. The team was poised to sign an agreement with UNDP last December in Copenhagen to administer the fund. Correa called off the signing at the last minute, questioning the breadth of the Initiative’s conservation efforts and UNDP’s proposed six-person administrative body, three appointed by Ecuador, two by contributing nations, and one by UNDP. This joint control structure apparently sparked Correa’s tirade about shame and dignity.

Correa’s impulsivity and poor word choice have gotten him into trouble before. Acosta, another former key PAIS ally, resigned as president of the Constituent Assembly in June 2008, in the final stages of drafting the nation’s new Constitution, when Correa set a vote deadline Acosta felt hindered the democratic process for this major undertaking. The President has had frequent tussles with indigenous and environmental organizations over mining issues, on several occasions crossing the line from staking out an economically pragmatic political position to name-calling of “childish ecologists.”

Within a couple of weeks of the blowup, the government had backpedaled, withdrawing the June deadline, appointing a new negotiating team, and reasserting the position that the government’s “first option” is to leave the oil in the ground. At the same time, Petroecuador began work on a new pipeline near Yasuní, part of the infrastructure needed for ITT production, pursuant to a 2007 Memorandum of Understanding with several foreign oil companies.

If the People Lead...

Amid the doubts and mixed messages, proponents are fighting to save the Initiative as a cornerstone in the creation of a post-petroleum Ecuador and ultimately a post-petroleum world. In media interviews after his resignation, Sevilla stressed that he would keep working to ensure that the Initiative would not fail. The Constitution provides for a public referendum prior to extracting oil from protected areas like Yasuní, he noted. “If the president doesn’t want to assume his responsibility as leader...let’s pass the responsibility to the public.” In fact, 75% of respondents in a January poll in Quito and Guayaquil, the country’s two largest cities, indicated that they would vote to not extract the ITT oil.

Martinez and Sáenz concur that just as the Initiative emerged from widespread organizing efforts, its success will come from the people. “This is the moment to define ourselves and develop an economic model not based on petroleum,” Salazar says. “We have other knowledge, we have minerals, water. We need to change our consciousness and end the economic dependence on one resource.”

Elissa Dennis is a consultant to nonprofit affordable housing developers with Community Economics, Inc. in Oakland, CA. She is traveling, primarily in Latin America, during a sabbatical year.