By Bertrand Russel, The Basic Writings of Bertrand Russell, 1934/1961

|

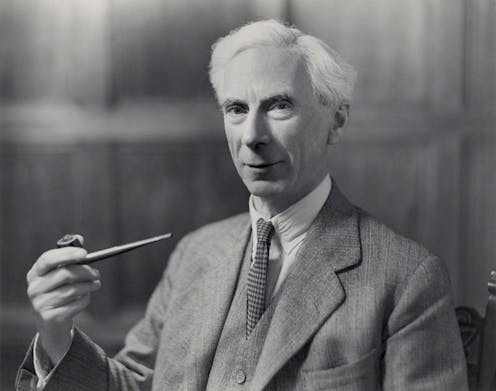

| Bertrand Russell in 1935. Photo: Creative Commons |

The contributions of Marx and Engels to theory were twofold: there was Marx’s theory of surplus value, and there was their joint theory of historical development, called ‘dialectical materialism’. We will consider first the latter, which seems to me both more true and more important than the former.

Let us, in the first place, endeavour to be clear as to what the theory of dialectical materialism is. It is a theory which has various elements. Metaphysically it is materialistic: in method it adopts a form of dialectic suggested by Hegel, but differing from his in many important respects. It takes over from Hegel an outlook which is evolutionary, and in which the stages in evolution can be characterized in clear logical terms. These changes are of the nature of development, not so much in an ethical as in a logical sense—that is to say, they proceed according to a plan which a man of sufficient intellect could, thoeretically, foretell, and which Marx himself professes to have foretold, in its main outlines, up to the moment of the universal establishment of Communism. The materialism of its metaphysics is translated, where human affairs are concerned, into the doctrine that the prime cause of all social phenomena is the method of production and exchange prevailing at any given period. The clearest statements of the theory are to be found in Engels, in his Anti-Dühring, of which the relevant parts have appeared in England under the title: Socialism, Utopian and Scientific. A few extracts will help to provide us with our text:

‘It was seen that all past history, with the exception of its primitive stages, was the history of class struggles: that these warring classes of society are always the products of the modes of production and of exchange—in a word, of the economic conditions of their time; that the economic structure of society always furnishes the real basis, starting from which we can alone work out the ultimate explanation of the whole superstructure of juridicial and political institutions as well as of the religious, philosophical, and other ideas of a given historical period.’

The discovery of this principle, according to Marx and Engels, showed that the coming of Socialism was inevitable.

‘From that time forward Socialism was no longer an accidental discovery of this or that ingenious brain, but the necessary outcome of the struggle between two historically developed classes—the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Its task was no longer to manufacture a system of society as perfect as possible, but to examine the historico-economic succession of events from which these classes and their antagonism had of necessity sprung, and to discover in the economic conditions thus created the means of ending the conflict. But the Socialism of earlier days was as incompatible with this materialistic conception as the conception of Nature of the French materialists was with dialectics and modern natural science. The Socialism of earlier days certainly criticized the existing capitalistic mode of production and its consequences. But it could not explain them, and, therefore, could not get the mastery of them. It could only simply reject them as bad. The more strongly this earlier Socialism denounced the exploitation of the working class, inevitable under Capitalism, the less able was it clearly to show in what this exploitation consisted and how it arose.’

The same theory which is called Dialectical Materialism is also called the Materialist Conception of History. Engels says: ‘The materialist conception of history starts from the proposition that the production of the means to support human life and, next to production, the exchange of things produced, is the basis of all social structure; that in every society that has appeared in history, the manner in which wealth is distributed and society divided into classes or orders, is dependent upon what is produced, how it is produced, and how the products are exchanged. From this point of view the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men’s brains, not in man’s better insight into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange. They are to be sought, not in the philosophy, but in the economics of each particular epoch. The growing perception that existing social institutions are unreasonable and unjust, that reason has become unreason, and right wrong, is only proof that in the modes of production and exchange changes have silently taken place, with which the social order, adapted to earlier economic conditions, is no longer in keeping. From this it also follows that the means of getting rid of the incongruities that have been brought to light, must also be present, in a more or less developed condition, within the changed modes of production themselves. These means are not to be invented by deduction from fundamental principles, but are to be discovered in the stubborn facts of the existing system of production.’ dialectical materialism

The conflicts which lead to political upheavals are not primarily mental conflicts in the opinions and passions of human beings. ‘This conflict between productive forces and modes of production is not a conflict engendered in the mind of man, like that between original sin and divine justice. It exists, in fact, objectively outside us, independently of the will and actions even of the men that have brought it on. Modern Socialism is nothing but the reflex, in thought, of this conflict in fact; its ideal reflection in the minds, first, of the class directly suffering under it, the working class.’

There is a good statement of the materialist theory of history in an early joint work of Marx and Engels (1845–6), called German Ideology. It is there said that the materialist theory starts with the actual process of production of an epoch, and regards as the basis of history the form of economic life connected with this form of production and generated by it. This, they say, shows civil society in its various stages and in its action as the State. Moreover, from the economic basis the materialist theory explains such matters as religion, philosophy, and morals, and the reasons for the course of their development.

These quotations perhaps suffice to show what the theory is. A number of questions arise as soon as it is examined critically. Before going on to economics one is inclined to ask, first, whether materialism is true in philosophy, and second, whether the elements of Hegelian dialectic which are embedded in the Marxist theory of development can be justified apart from a full-fledged Hegelianism. Then comes the further question whether these metaphysical doctrines have any relevance to the historical thesis as regards economic development, and last of all comes the examination of this historical thesis itself. To state in advance what I shall be trying to prove, I hold (1) that materialism, in some sense, may be true, though it cannot be known to be so; (2) that the elements of dialectic which Marx took over from Hegel made him regard history as a more rational process than it has in fact been, convincing him that all changes must be in some sense progressive, and giving him a feeling of certainty in regard to the future, for which there is no scientific warrant; (3) that the whole of his theory of economic development may perfectly well be true if his metaphysic is false, and false if his metaphysic is true, and that but for the influence of Hegel it would never have occurred to him that a matter so purely empirical could depend upon abstract metaphysics;

(4) with regard to the economic interpretation of history, it seems to me very largely true, and a most important contribution to sociology; I cannot, however, regard it as wholly true, or feel any confidence that all great historical changes can be viewed as developments. Let us take these points one by one.

(1) Materialism. Marx’s materialism was of a peculiar kind, by no means identical with that of the eighteenth century. When he speaks of the ‘materialist conception of history’, he never emphasizes philosophical materialism, but only the economic causation of social phenomena. His philosophical position is best set forth (though very briefly) in his Eleven Theses on Feuerbach (1845). In these he says:

‘The chief defect of all previous materialism—including that of Feuerbach—is that the object (Gegenstand), the reality, sensibility, is only apprehended under the form of the object (Objekt) or of contemplation (Anschauung), but not as human sensible activity or practice, not subjectively. Hence it came about that the active side was developed by idealism in opposition to materialism....

‘The question whether objective truth belongs to human thinking is not a question of theory, but a practical question. The truth, i.e. the reality and power, of thought must be demonstrated in practice. The contest as to the reality or non-reality of a thought which is isolated from practice, is a purely scholastic question....

‘The highest point that can be reached by contemplative materialism, i.e. by materialism which does not regard sensibility as a practical activity, is the contemplation of isolated individuals in “bourgeois society”.

‘The standpoint of the old materialism is “bourgeois” society; the standpoint of the new is human society or socialized (vergesellschaftete) humanity.

‘Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, but the real task is to alter it.’

The philosophy advocated in the earlier part of these theses is that which has since become familiar to the philosophical world through the writings of Dr Dewey, under the name of pragmatism or instrumentalism. Whether Dr Dewey is aware of having been anticipated by Marx, I do not know, but undoubtedly their opinions as to the metaphysical status of matter are virtually identical. In view of the importance attached by Marx to his theory of matter, it may be worth while to set forth his view rather more fully.

The conception of ‘matter’, in old-fashioned materialism, was bound up with the conception of ‘sensation’. Matter was regarded as the cause of sensation, and originally also as its object, at least in the case of sight and touch. Sensation was regarded as something in which a man is passive, and merely receives impressions from the outer world. This conception of sensation as passive is, however—so the instrumentalists contend—an unreal abstraction, to which nothing actual corresponds. Watch an animal receiving impressions connected with another animal: its nostrils dilate, its ears twitch, its eyes are directed to the right point, its muscles become taut in preparation for appropriate movements. All this is action, mainly of a sort to improve the informative quality of impressions, partly such as to lead to fresh action in relation to the object. A cat seeing a mouse is by no means a passive recipient of purely contemplative impressions. And as a cat with a mouse, so is a textile dialectical materialism manufacturer with a bale of cotton. The bale of cotton is an opportunity for action, it is something to be transformed. The machinery by which it is to be transformed is explicitly and obviously a product of human activity. Roughly speaking, all matter, according to Marx, is to be thought of as we naturally think of machinery: it has a raw material giving opportunity for action, but in its completed form it is a human product.

Philosophy has taken over from the Greeks a conception of passive contemplation, and has supposed that knowledge is obtained by means of contemplation. Marx maintains that we are always active, even when we come nearest to pure ‘sensation’: we are never merely apprehending our environment, but always at the same time altering it. This necessarily makes the older conception of knowledge inapplicable to our actual relations with the outer world. In place of knowing an object in the sense of passively receiving an impression of it, we can only know it in the sense of being able to act upon it successfully. That is why the test of all truth is practical. And since we change the object when we act upon it, truth ceases to be static, and becomes something which is continually changing and developing. That is why Marx calls his materialism ‘dialectical’, because it contains within itself, like Hegel’s dialectic, an essential principle of progressive change.

I think it may be doubted whether Engels quite understood Marx’s views on the nature of matter and on the pragmatic character of truth; no doubt he thought he agreed with Marx, but in fact he came nearer to orthodox materialism.1 Engels explains ‘historical materialism’, as he understands it, in an Introduction, written in 1892, to his Socialism, Utopian and Scientific. Here, the part assigned to action seems to be reduced to the conventional task of scientific verification. He says: ‘The proof of the pudding is in the eating. From the moment we turn to our own use these objects, according to the qualities we perceive in them, we put to an infallible test the correctness or otherwise of our sense-perceptions. . . . Not in one single instance, so far, have we been led to the conclusion that our sense-perceptions, scientifically controlled, induce in our minds ideas respecting the outer world that are, by their very nature, at variance with reality, or that there is an inherent incompatibility between the outer world and our sense-perceptions of it.’

There is no trace, here, of Marx’s pragmatism, or of the doctrine that sensible objects are largely the products of our own activity. But there is also no sign of any consciousness of disagreement with Marx. It may be that Marx modified his views in later life, but it seems more probable that, on this subject as on some others, he held two different views simultaneously, and applied the one or the other as suited the purpose of his argument. He certainly held that some propositions were ‘true’ in a more than pragmatic sense. When, in Capital, he sets forth the cruelties of the industrial system as reported by Royal Commissions, he certainly holds that these cruelties really took place, and not only that successful action will result from supposing that they took place. Similarly, when he prophesies the Communist revolution, he believes that there will be such an event, not merely that it is convenient to think so. His pragmatism must, therefore, have been only occasional—in fact when, on pragmatic grounds, it was justified by being convenient.

It is worth nothing that Lenin, who does not admit any divergence between Marx and Engels, adopts in his Materialism and Empirio-Criticism a view which is more nearly that of Engels than that of Marx.

For my part, while I do not think that materialism can be proved, I think Lenin is right in saying that it is not disproved by modern physics. Since his time, and largely as a reaction against his success, respectable physicists have moved further and further from materialism, and it is naturally supposed, by themselves and by the general public, that it is physics which has caused this movement. I agree with Lenin that no substantially new argument has emerged since the time of Berkeley, with one exception. This one exception, oddly enough, is the argument set forth by Marx in his theses on Feuerbach, and completely ignored by Lenin. If there is no such thing as sensation, if matter as something which we passively apprehend is a delusion, and if ‘truth’ is a practical rather than a theoretical conception, then old-fashioned materialism, such as Lenin’s, becomes untenable. And Berkeley’s view becomes equally untenable, since it removes the object in relation to which we are active. Marx’s instrumentalist theory, though he calls it materialistic, is really not so. As against materialism, its arguments have indubitably much force. Whether it is ultimately valid is a difficult question, as to which I have deliberately refrained from expressing an opinion, since I could not do so without writing a complete philosophical treatise.

(2) Dialectic in history. The Hegelian dialectic was a full-blooded affair. If you started with any partial concept and meditated on it, it would presently turn into its opposite; it and its opposite would combine into a synthesis, which would, in turn, become the starting point of a similar movement, and so on until you reached the Absolute Idea, on which you could reflect as long as you liked without discovering any new contradictions. The historical development of the world in time was merely an objectification of this process of thought. This view appeared possible to Hegel, because for him mind was the ultimate reality; for Marx, on the contrary, matter is the ultimate reality. Nevertheless he continues to think that the world develops according to a logical formula. To Hegel, the development of history is as logical as a game of chess. Marx and Engels keep the rules of chess, while supposing that the chessmen move themselves in accordance with the laws of physics, without the intervention of a player. In one of the quotations from Engels which I gave earlier, he says: ‘The means of getting rid of the incongruities that have been brought to light, must also be present, in a more or less developed dialectical materialism condition, within the changed modes of production themselves.’ This ‘must’ betrays a relic of the Hegelian belief that logic rules the world. Why should the outcome of a conflict in politics always be the establishment of some more developed system? This has not, in fact, been the case in innumerable instances. The barbarian invasion of Rome did not give rise to more developed economic forms, nor did the expulsion of the Moors from Spain, or the destruction of the Albigenses in the South of France. Before the time of Homer the Mycenaean civilization had been destroyed, and it was many centuries before a developed civilization again emerged in Greece. The examples of decay and retrogression are at least as numerous and as important in history as the examples of development. The opposite view, which appears in the works of Marx and Engels, is nothing but nineteenth-century optimism.

This is a matter of practical as well as theoretical importance. Communists always assume that conflicts between Communism and capitalism, while they may for a time result in partial victories for capitalism, must in the end lead to the establishment of Communism. They do not envisage another possible result, quite as probable, namely, a return to barbarism. We all know that modern war is a somewhat serious matter, and that in the next world war it is likely that large populations will be virtually exterminated by poison gases and bacteria. Can it be seriously supposed that after a war in which the great centres of population and most important industrial plant had been wiped out, the remaining population would be in a mood to establish scientific Communism? Is it not practically certain that the survivors would be in a mood of gibbering and superstitious brutality, fighting all against all for the last turnip or the last mangel-wurzel? Marx used to do his work in the British Museum, but after the Great War the British Government placed a tank just outside the museum, presumably to teach the intellectuals their place. Communism is a highly intellectual, highly civilized doctrine, which can, it is true, be established, as it was in Russia, after a slight preliminary skirmish, such as that of 1914–18, but hardly after a really serious war. I am afraid the dogmatic optimism of the Communist doctrine must be regarded as a relic of Victorianism.

There is another curious point about the Communist interpretation of the dialectic. Hegel, as everyone knows, concluded his dialectical account of history with the Prussian State, which, according to him, was the perfect embodiment of the Absolute Idea. Marx, who had no affection for the Prussian State, regarded this as a lame and impotent conclusion. He said that the dialectic should be essentially revolutionary, and seemed to suggest that it could not reach any final static resting-place. Nevertheless we hear nothing about the further revolutions that are to happen after the establishment of Communism. In the last paragraph of La Misère de la Philosophie he says:

‘It is only in an order of things in which there will no longer be classes or class-antagonism that social evolutions will cease to be political revolutions.’

What these social evolutions are to be, or how they are to be brought about without the motive power of class conflict, Marx does not say. Indeed, it is hard to see how, on his theory, any further evolution would be possible. Except from the point of view of present-day politics, Marx’s dialectic is no more revolutionary than that of Hegel. Moreover, since all human development has, according to Marx, been governed by conflicts of classes, and since under Communism there is to be only one class, it follows that there can be no further development, and that mankind must go on for ever and ever in a state of Byzantine immobility. This does not seem plausible, and it suggests that there must be other possible causes of political events besides those of which Marx has taken account.

(3) Irrelevance of Metaphysics. The belief that metaphysics has any bearing upon practical affairs is, to my mind, a proof of logical incapacity. One finds physicists with all kinds of opinions: some follow Hume, some Berkeley, some are conventional Christians, some are materialists, some are sensationalists, some even are solipsists. This makes no difference whatever to their physics. They do not take different views as to when eclipses will occur, or what are the conditions of the stability of a bridge. That is because, in physics, there is some genuine knowledge, and whatever metaphysical beliefs a physicist may hold must adapt themselves to this knowledge. In so far as there is any genuine knowledge in the social sciences, the same thing is true. Whenever metaphysics is really useful in reaching a conclusion, that is because the conclusion cannot be reached by scientific means, i.e. because there is no good reason to suppose it true. What can be known can be known without metaphysics, and whatever needs metaphysics for its proof cannot be proved. In actual fact Marx advances in his books much detailed historical argument, in the main perfectly sound, but none of this in any way depends upon materialism. Take, for example, the fact that free competition tends to end in monopoly. This is an empirical fact, the evidence for which is equally patent whatever one’s metaphysic may happen to be. Marx’s metaphysic comes in in two ways: on the one hand, by making things more cut and dried and precise than they are in real life; on the other hand, in giving him a certainty about the future which goes beyond what a scientific attitude would warrant. But in so far as his doctrines of historical development can be shown to be true, his metaphysic is irrelevant. The question whether Communism is going to become universal is quite independent of metaphysics. It may be that a metaphysic is helpful in the fight: early Mohammedan conquests were much facilitated by the belief that the faithful who died in battle went straight to Paradise, and similarly the efforts of Communists may be stimulated by the belief that there is a God called Dialectical Materialism who is fighting on dialectical materialism 485 their side, and will, in His own good time, give them the victory. On the other hand, there are many people to whom it is repugnant to have to profess belief in propositions for which they see no evidence, and the loss of such people must be reckoned as a disadvantage resulting from the Communist metaphysic.

(4) Economic Causation in History. In the main I agree with Marx that economic causes are at the bottom of most of the great movements in history, not only political movements, but also those in such departments as religion, art, and morals. There are, however, important qualifications to be made. In the first place, Marx does not allow nearly enough for the time-lag. Christianity, for example, arose in the Roman Empire, and in many respects bears the stamp of the social system of that time, but Christianity has survived through many changes. Marx treats it as moribund. ‘When the ancient world was in its last throes, the ancient religions were overcome by Christianity. When Christian ideas succumbed in the eighteenth century to rationalist ideas, feudal society fought its death-battle with the then revolutionary bourgeoisie.’ (Manifesto of the Communist Party by Karl Marx and F. Engels.) Nevertheless, in his own country it remained the most powerful obstacle to the realization of his own ideas,2 and throughout the Western world its political influence is still enormous. I think it may be conceded that new doctrines that have any success must bear some relation to the economic circumstances of their age, but old doctrines can persist for many centuries without any such relation of any vital kind.

Another point where I think Marx’s theory of history is too definite is that he does not allow for the fact that a small force may tip the balance when two great forces are in approximate equilibrium. Admitting that the great forces are generated by economic causes, it often depends upon quite trivial and fortuitous events which of the great forces gets the victory. In reading Trotsky’s account of the Russian Revolution, it is difficult to believe that Lenin made no difference, but it was touch and go whether the German Government allowed him to get to Russia. If the minister concerned had happened to be suffering from dyspepsia on a certain morning, he might have said ‘No’ when in fact he said ‘Yes’, and I do not think it can be rationally maintained that without Lenin the Russian Revolution would have achieved what it did. To take another instance: if the Prussians had happened to have a good general at the battle of Valmy, they might have wiped out the French Revolution. To take an even more fantastic example, it may be maintained quite plausibly that if Henry VIII had not fallen in love with Anne Boleyn, the United States would not now exist. For it was owing to this event that England broke with the Papacy, and therefore did not acknowledge the Pope’s gift of the Americas to Spain and Portugal. If England had remained Catholic, it is probable that what is now the United States would have been part of Spanish America.

This brings me to another point in which Marx’s philosophy of history was faulty. He regards economic conflicts as always conflicts between classes, whereas the majority of them have been between races or nations. English industrialism of the early nineteenth century was internationalist, because it expected to retain its monopoly of industry. It seemed to Marx, as it did to Cobden, that the world was going to be increasingly cosmopolitan. Bismarck, however, gave a different turn to events, and industrialism ever since has grown more and more nationalistic. Even the conflict between capitalism and Communism takes increasingly the form of a conflict between nations. It is true, of course, that the conflicts between nations are very largely economic, but the grouping of the world by nations is itself determined by causes which are in the main not economic.

Another set of causes which have had considerable importance in history are those which may be called medical. The Black Death, for example, was an event of whose importance Marx was well aware, but the causes of the Black Death were only in part economic. Undoubtedly it would not have occurred among populations at a higher economic level, but Europe had been quite as poor for many centuries as it was in 1348, so that the proximate cause of the epidemic cannot have been poverty. Take again such a matter as the prevalence of malaria and yellow fever in the tropics, and the fact that these diseases have now become preventable. This is a matter which has very important economic effects, though not itself of an economic nature.

Much the most necessary correction in Marx’s theory is as to the causes of changes in methods of production. Methods of production appear in Marx as prime causes, and the reasons for which they change from time to time are left completely unexplained. As a matter of fact, methods of production change, in the main, owing to intellectual causes, owing, that is to say, to scientific discoveries and inventions. Marx thinks that discoveries and inventions are made when the economic situation calls for them. This, however, is a quite unhistorical view. Why was there practically no experimental science from the time of Archimedes to the time of Leonardo? For six centuries after Archimedes the economic conditions were such as should have made scientific work easy. It was the growth of science after the Renaissance that led to modern industry. This intellectual causation of economic processes is not adequately recognized by Marx.

History can be viewed in many ways, and many general formulae can be invented which cover enough of the ground to seem adequate if the facts are carefully selected. I suggest, without undue solemnity, the following alternative theory of the causation of the industrial revolution: industrialism is due to modern science, modern science is due to Galileo, Galileo is due to Copernicus, Copernicus is due to the Renaissance, the Renaissance is due to the fall of Constantinople, the fall of Constantinople is due to the migration of the Turks, the migration of the Turks is due to the desiccation of Central Asia. Therefore the fundamental study in searching for historical causes is hydrography. (Freedom and Organization, London: Allen & Unwin; Freedom Versus Organization, New York: W. W. Norton, 1934.)

Notes

1. Cf. Sidney Hook, Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx, p. 32. 2 ‘For Germany’, wrote Marx in 1844, ‘the critique of religion is essentially completed.’

Notes

1. Cf. Sidney Hook, Towards the Understanding of Karl Marx, p. 32. 2 ‘For Germany’, wrote Marx in 1844, ‘the critique of religion is essentially completed.’

No comments:

Post a Comment