Rothschild’s giraffe populations are slowly recovering. Credit: Denis-Huot/NPL/SPL

Nearly one-third of the world’s species are threatened with extinction. But for some iconic animals, years of conservation efforts are finally paying off.

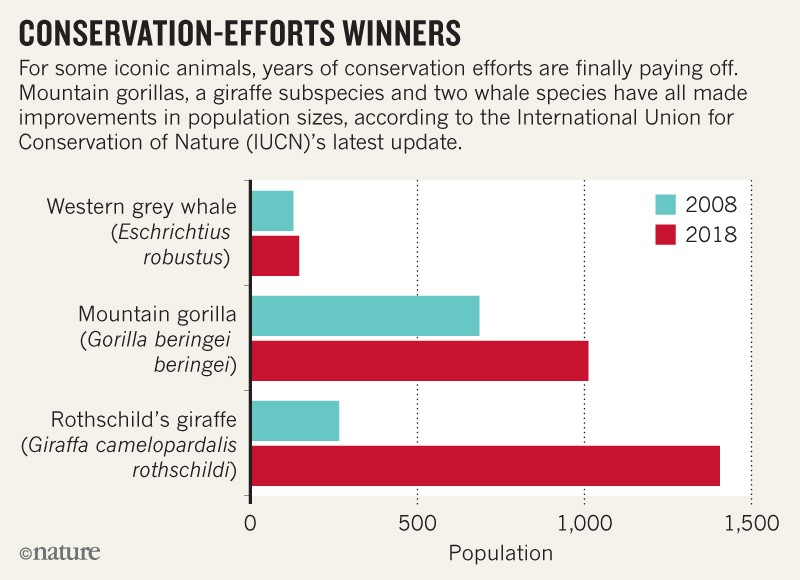

Mountain gorillas, a subspecies of giraffe and two types of whale are all in a lower conservation category — meaning they are considered less vulnerable to extinction — than the last time they were assessed.

This is according to a 14 November update to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, which catalogues the conservation status of the world’s animals, fungi and plants.

The IUCN puts these successes down to years of collaborative effort among governments, businesses and society to help species to recover.

“We can see the positive impact that having this long-term investment in conservation can have,” says Tara Stoinski, president of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International in Atlanta, Georgia.

Species revival

Mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) live in the mountain rainforests that straddle Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where habitat destruction from agricultural expansion, disease and civil unrest have severely threatened their populations. In 2008, mountain gorillas numbered only 680 individuals, meriting their classification at the time as ‘critically endangered’, which is exceedingly close to extinction.

But because of extreme conservation measures, including daily monitoring and protection by armed guards, says Stoinski, the gorilla populations have risen at last count to 1,004. The IUCN has accordingly lowered their conservation status to ‘endangered’, which indicates that their populations are small and still highly vulnerable to extinction, but less so than before (See ‘Conservation-efforts winners’) .

Illegal hunting, habitat destruction and the spread of human agriculture have similarly caused populations of Rothschild’s giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildii), found mostly in Uganda and Kenya, to drop from as many as 2,500 individuals in the 1960s to around 500 between 2006 and 2009.

After being categorized as endangered on the 2010 IUCN Red List, legal protections, the reintroduction of a handful of giraffes to parts of Kenya and the development of species recovery plans have boosted the giraffe populations to around 1,470 mature individuals. The population is now designated as ‘near threatened’, which means it has improved but is still small enough that it could easily become endangered again.

Wars on whaling

Fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) and western grey whales (Eschrichtius robustus) in the western Pacific were hunted nearly to extinction in the early-to-mid-twentieth century. But after commercial whaling activities on both species ceased in the 1980s the populations steadily climbed.

Combined estimates from different parts of the world between 2006 and 2008 put the then-endangered fin-whale populations at around 62,000 animals. Current estimates reach nearly 100,000 mature individuals — enough to move their status to ‘vulnerable’.

Western grey whales made a similar climb, albeit much more incrementally, from being critically endangered, with roughly 120 individuals in 2007, to endangered in 2018, amounting to 170–180 individuals.

“It really does just come down to the fact that if we don’t kill them, they increase towards recovery,” says Randall Reeves, chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Cetacean Specialist Group, in Hudson, Canada .

Despite the improvements, the IUCN says, there are still pressures that threaten each of these species. Whales are at risk of getting entangled in fishing gear. Illegal hunting and habitat destruction still threaten giraffes. And mountain gorillas are still susceptible to environmental disasters and disease epidemics, including recurring Ebola outbreaks. “We can’t just tick this off and move on to something else,” Stoinski says.

No comments:

Post a Comment