|

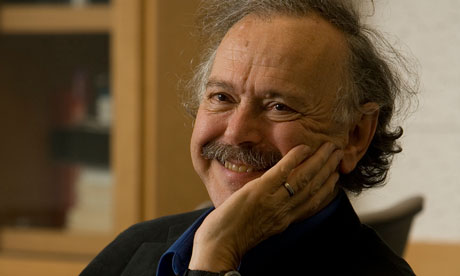

| Richard A. Muller |

By Richard A. Muller, The New York Times, July 30, 2012

CALL me a converted skeptic. Three years ago I identified problems in

previous climate studies that, in my mind, threw doubt on the very existence of

global warming. Last year, following an intensive research effort involving a

dozen scientists, I concluded that global warming was real and that the prior

estimates of the rate of warming were correct. I’m now going a step further:

Humans are almost entirely the cause.

My total turnaround, in such a short time, is the result of careful

and objective analysis by the Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature project,

which I founded with my daughter Elizabeth. Our results show that the average

temperature of the earth’s land has risen by two and a half degrees Fahrenheit

over the past 250 years, including an increase of one and a half degrees over

the most recent 50 years. Moreover, it appears likely that essentially all of

this increase results from the human emission of greenhouse gases.

These findings are stronger than those of the Intergovernmental Panel

on Climate Change, the United Nations group that defines the scientific and

diplomatic consensus on global warming. In its 2007 report, the I.P.C.C.

concluded only that most of the warming of the prior 50 years could be

attributed to humans. It was possible, according to the I.P.C.C. consensus

statement, that the warming before 1956 could be because of changes in solar

activity, and that even a substantial part of the more recent warming could be

natural.

Our Berkeley Earth approach used sophisticated statistical methods developed

largely by our lead scientist, Robert Rohde, which allowed us to determine

earth land temperature much further back in time. We carefully studied issues

raised by skeptics: biases from urban heating (we duplicated our results using

rural data alone), from data selection (prior groups selected fewer than 20

percent of the available temperature stations; we used virtually 100 percent),

from poor station quality (we separately analyzed good stations and poor ones)

and from human intervention and data adjustment (our work is completely

automated and hands-off). In our papers we demonstrate that none of these

potentially troublesome effects unduly biased our conclusions.

The historic temperature pattern we observed has abrupt dips that

match the emissions of known explosive volcanic eruptions; the particulates

from such events reflect sunlight, make for beautiful sunsets and cool the

earth’s surface for a few years. There are small, rapid variations attributable

to El Niño and other ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream; because of such

oscillations, the “flattening” of the recent temperature rise that some people

claim is not, in our view, statistically significant. What has caused the

gradual but systematic rise of two and a half degrees? We tried fitting the

shape to simple math functions (exponentials, polynomials), to solar activity

and even to rising functions like world population. By far the best match was

to the record of atmospheric carbon dioxide, measured from atmospheric samples

and air trapped in polar ice.

Just as important, our record is long enough that we could search for

the fingerprint of solar variability, based on the historical record of

sunspots. That fingerprint is absent. Although the I.P.C.C. allowed for the

possibility that variations in sunlight could have ended the “Little Ice Age,”

a period of cooling from the 14th century to about 1850, our data argues

strongly that the temperature rise of the past 250 years cannot be attributed

to solar changes. This conclusion is, in retrospect, not too surprising; we’ve

learned from satellite measurements that solar activity changes the brightness

of the sun very little.

How definite is the attribution to humans? The carbon dioxide curve

gives a better match than anything else we’ve tried. Its magnitude is

consistent with the calculated greenhouse effect — extra warming from trapped

heat radiation. These facts don’t prove causality and they shouldn’t end

skepticism, but they raise the bar: to be considered seriously, an alternative

explanation must match the data at least as well as carbon dioxide does. Adding

methane, a second greenhouse gas, to our analysis doesn’t change the results.

Moreover, our analysis does not depend on large, complex global climate models,

the huge computer programs that are notorious for their hidden assumptions and

adjustable parameters. Our result is based simply on the close agreement

between the shape of the observed temperature rise and the known greenhouse gas

increase.

It’s a scientist’s

duty to be properly skeptical. I still find that much, if not most, of what is

attributed to climate change is speculative, exaggerated or just plain wrong.

I’ve analyzed some of the most alarmist claims, and my skepticism about them

hasn’t changed.

Hurricane Katrina cannot be attributed to global warming. The number

of hurricanes hitting the United States has been going down, not up; likewise

for intense tornadoes. Polar bears aren’t dying from receding ice, and the

Himalayan glaciers aren’t going to melt by 2035. And it’s possible that we are

currently no warmer than we were a thousand years ago, during the “Medieval

Warm Period” or “Medieval Optimum,” an interval of warm conditions known from

historical records and indirect evidence like tree rings. And the recent warm

spell in the United States happens to be more than offset by cooling elsewhere

in the world, so its link to “global” warming is weaker than tenuous.

The careful analysis by our team is laid out in five scientific papers

now online at BerkeleyEarth.org.

That site also shows our chart of temperature from 1753 to the present, with

its clear fingerprint of volcanoes and carbon dioxide, but containing no

component that matches solar activity. Four of our papers have undergone

extensive scrutiny by the scientific community, and the newest, a paper with

the analysis of the human component, is now posted, along with the data and

computer programs used. Such transparency is the heart of the scientific

method; if you find our conclusions implausible, tell us of any errors of data

or analysis.

What about the future? As carbon dioxide emissions increase, the

temperature should continue to rise. I expect the rate of warming to proceed at

a steady pace, about one and a half degrees over land in the next 50 years,

less if the oceans are included. But if China continues its rapid economic growth

(it has averaged 10 percent per year over the last 20 years) and its vast use

of coal (it typically adds one new gigawatt per month), then that same warming

could take place in less than 20 years.

Science

is that narrow realm of knowledge that, in principle, is universally accepted.

I embarked on this analysis to answer questions that, to my mind, had not been

answered. I hope that the Berkeley Earth analysis will help settle the

scientific debate regarding global warming and its human causes. Then comes the

difficult part: agreeing across the political and diplomatic spectrum about

what can and should be done.

Richard A. Muller, a professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, and a former MacArthur Foundation fellow, is the author, most recently, of “Energy for Future Presidents: The Science Behind the Headlines.”

Richard A. Muller, a professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, and a former MacArthur Foundation fellow, is the author, most recently, of “Energy for Future Presidents: The Science Behind the Headlines.”

No comments:

Post a Comment