By Justin Gillis,The New York Times, December 30, 2015

|

| Thirteen inches of rain fell on Hoinster Pass in Lake District, U.LK. in 24 hours. |

What is going on with the weather?

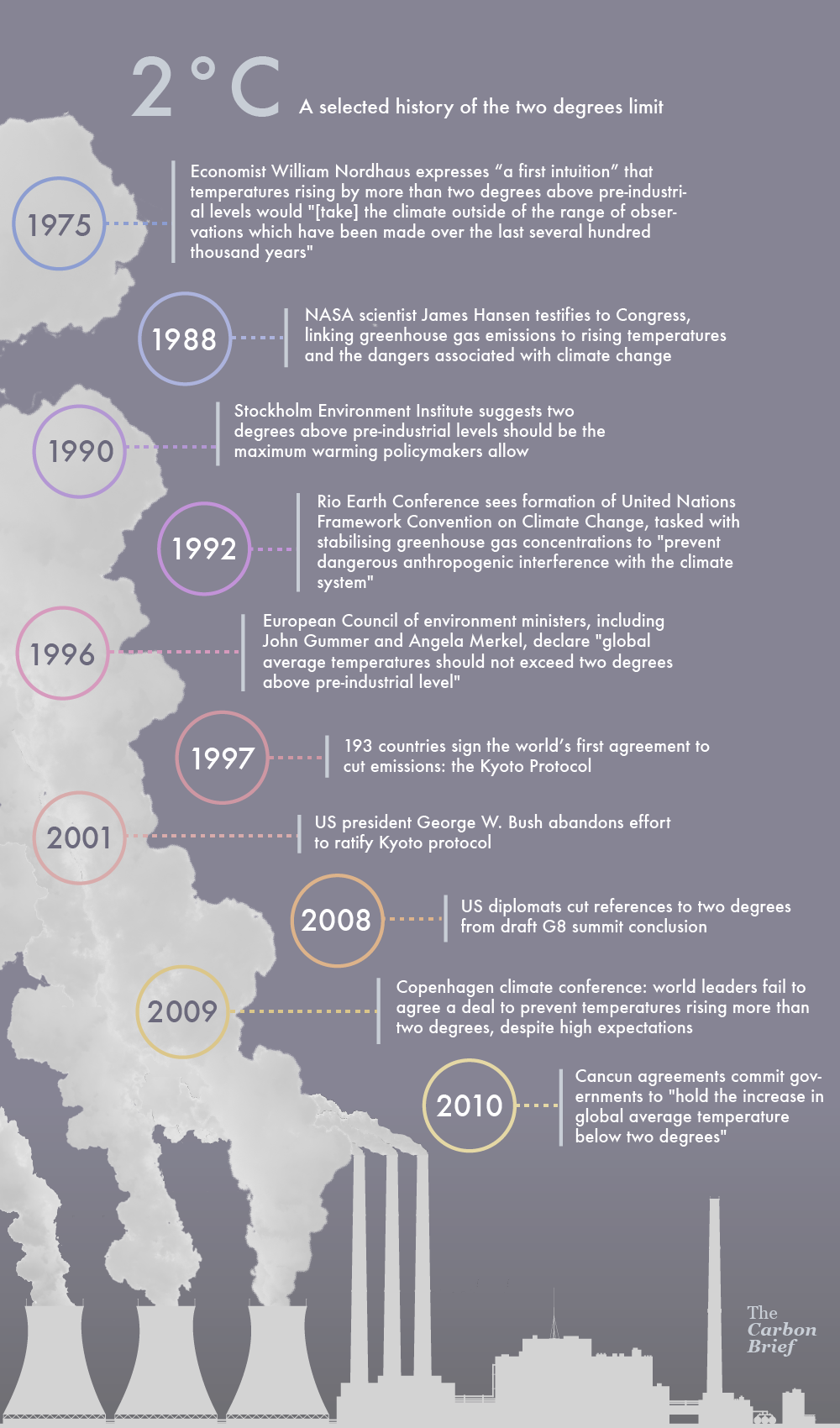

With tornado outbreaks in the South, Christmas temperatures that sent trees into bloom in Central Park, drought in parts of Africa and historic floods drowning the old industrial cities of England, 2015 is closing with a string of weather anomalies all over the world.

The year, expected to be the hottest on record, may be over at midnight Thursday, but the trouble will not be. Rain in the central United States has been so heavy that major floods are beginning along the Mississippi River and are likely to intensify in coming weeks. California may lurch from drought to flood by late winter. Most serious, millions of people could be threatened by a developing food shortage in southern Africa.

Scientists say the most obvious suspect in the turmoil is the climate pattern called El Niño, in which the Pacific Ocean for the last few months has been dumping immense amounts of heat into the atmosphere. Because atmospheric waves can travel thousands of miles, the added heat and accompanying moisture have been playing havoc with the weather in many parts of the world.

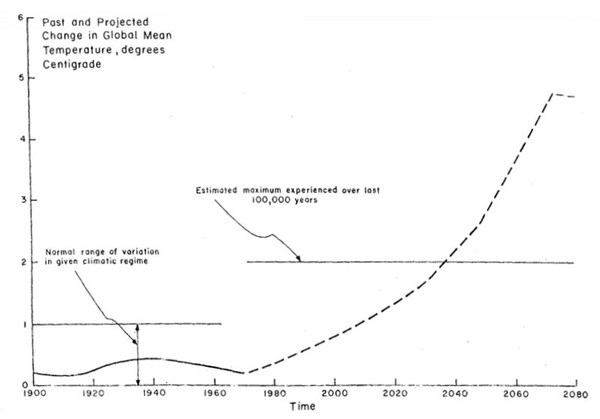

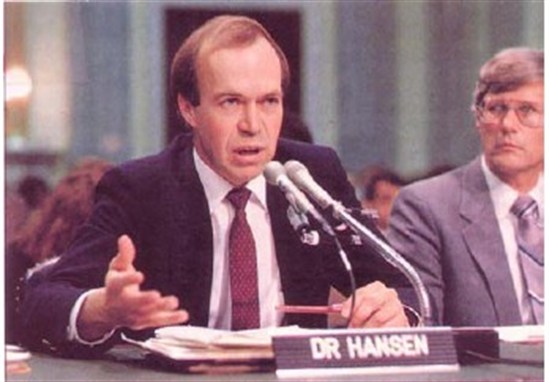

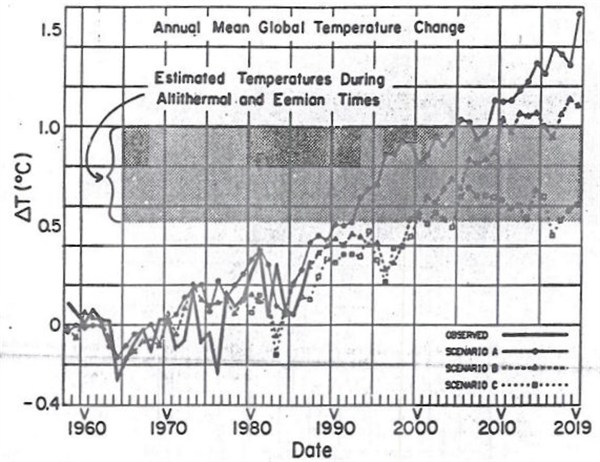

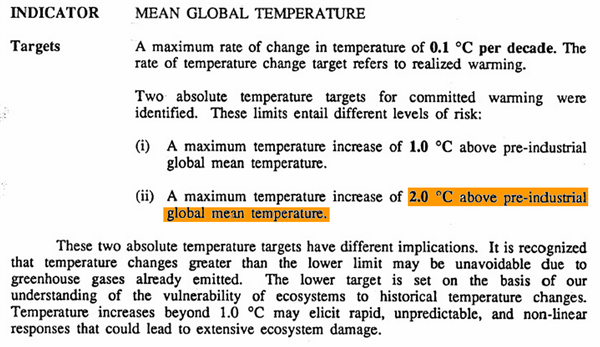

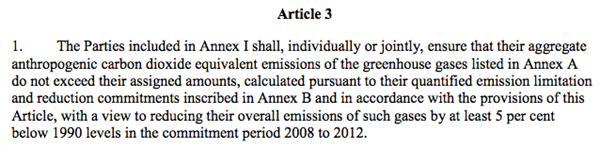

But that natural pattern of variability is not the whole story. This El Niño, one of the strongest on record, comes atop a long-term heating of the planet caused by mankind’s emissions of greenhouse gases. A large body of scientific evidence says those emissions are making certain kinds of extremes, such as heavy rainstorms and intense heat waves, more frequent.

Coincidence or not, every kind of trouble that the experts have been warning about for years seems to be occurring at once.

“As scientists, it’s a little humbling that we’ve kind of been saying this for 20 years now, and it’s not until people notice daffodils coming out in December that they start to say, ‘Maybe they’re right,’ ” said Myles R. Allen, a climate scientist at Oxford University in Britain.

Dr. Allen’s group, in collaboration with American and Dutch researchers, recently completed a report calculating that extreme rainstorms in the British Isles in December had become about 40 percent more likely as a consequence of human emissions. That document — inspired by a storm in early December that dumped stupendous rains, including 13 inches on one town in 24 hours — was barely finished when the skies opened up again.

Emergency crews have since been scrambling to rescue people from flooded homes in Leeds, York and other cities. A dispute has erupted in Parliament about whether Britain is doing enough to prepare for a changing climate.

Dr. Allen does not believe that El Niño had much to do with the British flooding, based on historical evidence that the influence of the Pacific Ocean anomaly is fairly weak in that part of the world. In the Western Hemisphere, the strong El Niño is likely a bigger part of the explanation for the strange winter weather.

The northern tier of the United States is often warm during El Niño years, and indeed, weather forecasters months ago predicted such a pattern for this winter. But they did not go so far as to forecast that the temperature in Central Park on the day before Christmas would hit 72 degrees.

Matthew Rosencrans, head of forecast operations for the federal government’s Climate Prediction Center in College Park, Md., said that the El Niño was not the only natural factor at work. This winter, a climate pattern called the Arctic Oscillation is also keeping cold air bottled up in the high north, allowing heat and moisture to accumulate in the middle latitudes. That may be a factor in the recent heavy rains in states like Georgia and South Carolina, as well as in some of the other weather extremes, he said.

Although El Niños occur every three to seven years, most of them are of moderate intensity. They form when the westward trade winds in the Pacific weaken, or even reverse direction. That shift leads to a dramatic warming of the surface waters in the eastern Pacific.

“Clouds and storms follow the warm water, pumping heat and moisture high into the overlying atmosphere,” as NASA recently explained. “These changes alter jet stream paths and affect storm tracks all over the world.”

The current El Niño is only the third powerful El Niño to have occurred in the era of satellites and other sophisticated weather observations. It is a small data set from which to try to draw broad conclusions, and experts said they would likely be working for months or years to understand what role El Niño and other factors played in the weather extremes of 2015.

It is already clear, though, that the year will be the hottest ever recorded at the surface of the planet, surpassing 2014 by a considerable margin. That is a function both of the short-term heat from the El Niño and the long-term warming from human emissions. In both the Atlantic and Pacific, the unusually warm ocean surface is throwing extra moisture into the air, said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

Storms over land can draw moisture from as far as 2,000 miles away, he said, so the warm ocean is likely influencing such events as the heavy rain in the Southeast, as well as the record number of strong hurricanes and typhoons that occurred this year in the Pacific basin, with devastating consequences for island nations like Vanuatu.

“The warmth means there is more fuel for these weather systems to feed upon,” Dr. Trenberth said. “This is the sort of thing we will see more as we go decades into the future.”