By Amy Muldoon, International Socialist Review, Winter 2016-17

“By becoming accustomed to self-management, the workers are preparing for that time when private ownership of factories and works will be abolished, and the means of production, together with the buildings erected by the workers’ hands, will pass into the hands of the working class as a whole. Thus, whilst doing the small things, we must constantly bear in mind the great overriding objective towards which the working people is striving.” —Putilov works committee statement to shop committees, April 24 19171

The centennial of the Russian Revolution is a fitting time for Marxists and other radicals to reflect on the what still stands as the historical high point of revolutionary workers’ struggles. The Revolution was a multifaceted process. It was fueled not only by the resistance of workers to their crushing economic oppression under tsarism, but also by the mutinous movement of soldiers and sailors against World War I;

the aspirations of all classes for full democratic rights as citizens; developing national liberation struggles encompassing over half the Russian population; massive peasant revolts in the countryside; and even nascent struggles for women’s rights.

Yet among these multiple forces the working class played the pivotal role. The Revolution posed the possibility of remaking society, free from classes, through the vehicle of a national network of directly elected Soviets of Workers, Soldiers, and Peasant Deputies. The radical democratic character of the Soviets was based on a foundation of workers’ self-organization at the system’s heart: the point of production. As the Polish Marxist Rosa Luxemburg wrote, “Where the chains of capitalism are forged, there they must be broken,” and Russian workers built multiple tools to break the chains of their oppression.2

Foremost among the organizations workers created were the factory committees and trade unions. The development of these bodies follows the general trajectory of all of Russian society in 1917—from the spring of hope, through the hot summer of conflict, to the hardened polarization of the fall.

While many strains of left-wing thought today embrace the profound self-activity of the working class in the Russian Revolution, some see the Bolshevik Party as an outside influence in the revolution, manipulating the situation for its own political agenda. Modern authors like radical scholar Noam Chomsky, and his forebear Maurice Brinton articulate this anarchist version of events.3 While the Bolsheviks “adopted much of the rhetoric” of the masses, “their true commitments were quite different,” writes Chomsky. “In revolutionary Russia, Soviets and factory committees developed as instruments of struggle and liberation, with many flaws, but with a rich potential. Lenin and Trotsky, upon assuming power, immediately devoted themselves to destroying the liberatory potential of these instruments.”4

The narrative that the Bolsheviks acted as an outside force to hijack the Russian workers’ movement doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. In fact, the Bolsheviks weren’t an external body separate from the working class: the party was both the producer and the product of the workers’ struggles. Between February and October of 1917, the Bolshevik Party ballooned from 25,000 to 350,000 members. This was only possible because party activists were themselves an important part of the working class in Russia’s industrial centers, especially Petrograd. Their program matched the program of their fellow workers and soldiers, and their tactical leadership in daily struggles provided real gains. As one Menshevik eyewitness recounted of the Bolsheviks, “For the masses, they had become their own people, because they were always there, taking the lead in details as well as in the most important affairs of the factory or barracks. . . . The mass lived and breathed together with the Bolsheviks.”5

The Bolsheviks were not alone in contending for a working class audience: there were many parties and trends, all vying for leadership of the movement. Against the Bolsheviks were ranged a wide array of rivals and opponents: fellow Social Democrats like the moderate Mensheviks and the more left-wing Menshevik Internationalists, Socialist Revolutionaries (both the Left and Right variety),6 the Petersburg Interdistrict Committee7 and other socialist parties. Then there were the liberals in the Kadet Party in addition to the anarchists and syndicalists in smaller formations. Debates in a vibrant workers’ press as well as in the streets and workplaces meant a constant exposure to the different strategies, tactics, and analyses of contending parties.

The argument that the Bolsheviks manipulated Russian workers underestimates both the astuteness of the workers who joined the Bolsheviks and the heightened political atmosphere of 1917. Within the working class a battle of ideas raged through 1917. Bolshevik N. Krupskaya describes in her memoirs regularly witnessing all-night street debates in Petrograd soon after her return to the capitol. John Reed’s famous account noted that, “For months in Petrograd, and all over Russia, every street-corner was a public tribune.”8

In his booklet Factory Committees and Workers’ Control in Petrograd in 1917, David Mandel argues that the factory committees were not formed on the initiative of any party. They were created from below as a “practical response by workers to the looming economic crisis” and “the inactivity and active sabotage on the part of the factory owners and the coalition government of liberals and moderate socialists.” And yet, as he also notes, “The movement for workers’ control exemplifies the role of the Bolshevik Party, as an organic, democratically organized part of the working class, in giving rank-and-file initiatives organizational form and practical goals, and in linking them to the overall struggle for working-class political power.9

Workers in Russia built many kinds of organizations through 1917. This article will focus on factory committees and unions to reassert the centrality of the shop floor as the landscape for the revolutionary process.10 It will also highlight the indissoluble link between the maturation of the movement and the presence of the Bolshevik Party. Moving in roughly chronological order, the article will look at how the early period of hope and unity across Russian classes foundered on the limits of coalition with the capitalists. The cracking up of the unity of forces that ousted the tsar in February is often depicted through the debates over policy that dominated the Soviet and the Provisional Government (World War I loomed as the central issue); this article highlights the economic friction that led millions of workers to embrace a second insurrection against the February order. Last, the article aims to highlight the dialectical relationship between organization and consciousness and to reassert the material roots of political radicalization.

Roots of the rebellion

Russia at the opening of World War I was a society in the midst of a massive transformation. The Russian Empire encompassed over 150 million people, with 70 percent living in the countryside. Within this aging empire, modern capitalist enterprises had taken root, funded by foreign capital and nurtured by state ownership and intervention. The introduction of imported technology and capital allowed the development of concentrated centers of production within a society still characterized by medieval relations. Leon Trotsky called this process “combined and uneven development,” as Russia skipped many of the intermediary steps between feudalism and advanced capitalism, and fused the most backward and most forward elements of society together in one uneasy whole.11

The working class as social force was born in the 1890s. Though a small minority—just over 3 million in 1917—it was heavily concentrated in large cities and mining enterprises. In Petrograd, the heart of the workers’ movement, the number of factory workers grew from 73,200 in 1890 to 242,600 by 1914. The coming of World War I compounded this growth: Petrograd crammed another 150,000 workers into the city center by 1917. Metal works were the largest employer, accounting for 60 percent of factory workers. The Putilov Works in Petrograd employed 30,000, making it the world’s largest factory.12

Russian society lacked basic democratic rights; the franchise was severely restricted, and the Duma, or Russian parliament, was powerless. Basic freedoms, including the right to form unions, were also practically nonexistent. Corporal punishment, the age-old custom used by lords against peasants, was carried into factories. The first years following the turn of the twentieth century were marked by increasingly bitter strikes and workplace organizing, which culminated with workers and other disgruntled sections of Russian society rising against the autocracy in 1905. In January of that year, a peaceful procession of thousands of workers under the leadership of a mild reformist priest working with the police marched on the Winter Palace to deliver a petition for social and economic improvements. Troops opened fire, killing hundreds—producing a year of mass strikes, mutinies, and peasant rebellions.

The partial and decentralized organizing of the movement shifted qualitatively with the creation of citywide organizing centers to help develop the unprecedented strike movement. (For the whole period of 1895–1904, 431,000 workers went on strike, whereas in the year 1905, 2,863,000 workers struck).13 Called “soviets” (Russian for councils), these centers quickly spread to Moscow and St. Petersburg. They combined existing organizations’ representatives—from factory committees and unions—with directly elected representatives from every workplace.14 Not limited to a single shop or even a single industry, soviets represented the unified collective power of the class. But the Petersburg Soviet only lasted a few months, and, in December, after the defeat of an uprising in Moscow, the tsar was able to regroup and repress all forms of workers’ organizations and left political parties.

In this same period the system of electing factory elders (starosy) also spread. Through the course of the revolutionary upsurge in 1905, factory committees of elders participated in direct action to impose control over the production process. Despite the very radical name of “workers control,” factory committees were not viewed as inherently anticapitalist but as part of the bourgeois revolution that would replace the tsar. Workers considered the democratization of the workplace to be part of the process of democratizing Russian society as a whole.

The February Revolution and the emergence of the factory committees

On International Working Women’s Day, February 23, 1917, women workers in the capital launched a strike wave that would spell the end of tsarism in Russia. The strike movement escalated in the following days, driving the police from the streets and winning whole units of the army over to mutiny in support. Soviets of workers’ and soldiers’ deputies were created across Petrograd and then Russia, embracing factories, army, and navy units; and eventually electing peasant, student, and neighborhood delegates.

At the same time, the bourgeois segments of the Duma moved to establish a new political ruling body, the Provisional Government. While donning the mantle of the revolution, the Provisional Government sought to lay the basis for a bourgeois government, committed to the pursuit of Russia’s war aims and prepared to perpetually postpone land reform.

The conflict between one political organ based on bourgeois power and a second based in working-class self-organization was obvious. The precarious alliance between these two bodies—the Duma and the Soviet—was held together by the dominance of the moderate socialists in the Executive Committee of the All-Russian Soviet, which subordinated itself to the Provisional Government.

The February revolution was the product of a mounting strike wave. The years of reaction gave way to a resurgence of class struggle in 1912. The outbreak of World War I two years later brought this revival to a temporary halt—only to give it renewed vigour as the result of poverty and extreme exploitation produced by the war. Between August and December 1914, there were twenty-five strikes involving fewer than 20,000 workers in Petrograd; rising to 170 strikes involving 173,833 workers in 1915; and then up to 401 strikes and 513,737 workers in 1916.15 Then, with the exploision of the revolution in 1917, the number of strikes skyrocketed. By the time of the collapse of tsarism, factory inspectors had recorded strikes, the majority of them political, in “1,330 enterprises involving 676,000 workers . . . a larger number than for all of 1916.”16

It was during this surge of working-class struggle in February that factory committees sprang up across Russia. As historian Gennady Shkliarevsky notes, “The organization of factory committees began when the February strikes that led to the overthrow of the monarchy were still in progress. In many instances factory committees were organized even before local soviets came into existence.”17 The movement spread dramatically; by June 1917 three-quarters of Russian workers, according to one estimate, were involved in the movement.18

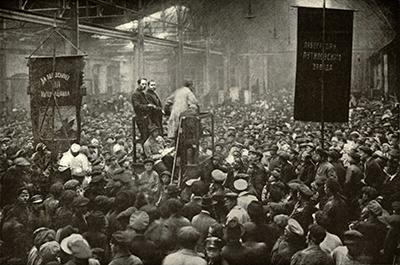

Company-wide assemblies of workers were also a common sight at the outbreak of the revolution and reflective of the deeply democratic nature of the movement. These meetings were a direct means by which workers debated and decided questions raised in the course of the struggle. “What a marvellous sight to see Putilovsky Zavod (the Putilov factory),” writes John Reed in Ten Days that Shook the World, “pour out its forty thousand to listen to Social Democrats, Socialist Revolutionaries, Anarchists, anybody, whatever they had to say, as long as they would talk!”19 The assemblies typically involved reports from factory delegates to district soviets, or invited speakers. Then representatives from different political fractions would speak, followed by debate and then voting on resolutions.20

These assemblies did not limit their discussions to economic questions; larger political questions were debated. A typical resolution passed June 15 by the Old Parviainen Machine-Construction Factory in Petrograd, for example, called on workers and peasants to make “a decisive break with the policy of imperialism and conciliation with imperialism—a policy aimed at reducing the Russian Revolution to the role of executor of the desires of international capital.”21

Assemblies also elected the factory-wide committees known as “works committees” which were tasked with wide-ranging responsibilities derived from the immediate needs of their workmates, but also those of the factory itself. Works committees assumed responsibility for keeping factories running. They set about securing raw materials like coal and pig iron from other factory committees, and sent representatives into the countryside to procure food through direct negotiation with peasants.

The character of the factory committees in the first months of the revolution was defensive, pushing back against the bosses’ undermining of the already weak economy. In the private sector, the imposition of worker supervision through the committees fought the economic dislocation that bosses were using to break up the working class movement. Workers (often correctly) suspected management sabotage of machinery or intentional idling of shops as a means of disciplining workers by creating de facto lockouts. Actual lockouts were similarly used to head off rising rank-and-file resistance.

The task of running some of the largest factories in the world was too great for a single committee, however. Within days of the overthrow of the tsar, works committees initiated the creation of “shop committees” to handle the vast details of workers’ control. Putilov workers established nearly forty shop committees, which were created to “defend the workers of the shop; to observe and organize internal order; to see that regulations were being followed; to control hiring and firing of workers; to resolve conflicts over wage-rates; to keep a close eye on working conditions; to check whether the military conscription of individual workers had been deferred, etc.”22

In addition, commissions were created to address the social and adminstrative needs of factory life. The Nevskii shipyard committee created six commissions, including: “a militia commission responsible for security of the factory, a food commission, a commission on culture and enlightenment, a technical-economic commission responsible for wages, safety, first aid and internal order, a reception commission responsible for the hiring and firing of workers, and finally a special commission which dealt with the clerical business of the committee.”23

Within a month of the February Revolution, 80 percent of Petrograd’s almost 400,000 factory workers were represented by a shop committee. The depiction above should make clear that far from being “spontaneous,” the factory committees were highly organized through durable and accountable leadership structures.

The experience of the factory committees illustrates the contradictory nature of what the revolution unleashed. While the factory committees were venues for profound cooperation and self-activity, supplanting management also meant that they assumed responsibility for labor discipline. The factory committees became disciplinary bodies, fining, suspending, and firing workers, particularly those who showed up drunk to work, or were chronically absent. In some workplaces where productivity slumped after the tsar’s fall, piece-rates were implemented to keep production up.

One of the most famous aspects of the workers’ revolt of February/March was the “carting out” of hated foremen. Historically in Russia, lacking stable unions, workers turned to direct action against abusive managers. They were thrown in wheelbarrows and given a rough ride to the factory gate, or in the case of enterprises located near the canals and rivers, into the water below. Naturally, in the strikes of the February Revolution, this practice returned with gusto. In a few isolated cases, managers were killed by their employes on the spot. These were often the immediate response to the sheer brutality of individuals, but they also represented an effort to clear away managers who were ineffective or sabotaging the factory, signaling the workers’ interest not just in improving conditions but in production itself.

The removal of factory administrators followed this pattern of removal in order to improve the efficiency and running of the factory (not just for abuse) and was implemented through the will of the committees in a deliberate manner. Historian David Mandel writes in Factory Committees and Workers’ Control in Petrograd in 1917: “At the First Power Station, the workers decided to remove the board of directors as ‘henchmen of the old regime, and recognizing their harmfulness from the economic point of view and their uselessness from the technical.’”24

Despite this incredible array of encroachments into the power of the state and bourgeoisie over production, the common understanding of the goal of the movement at this time was “workers’ control,” not “workers’ management”, supervision of production, not expropriation of the bosses. The factory committees monitored daily operations but accepted capitalist management of the economic and technical side of the enterprise. When worker management did appear in the early phase of the revolution, it did so because bosses abandoned their posts, not because workers drove them out.

As Mandel writes in Petrograd Workers and the Fall of the Old Régime, even in 1917, workers control didn’t mean an immediate transition to socialism:

The social content of the workers’ conception of the revolution included three basic elements: the eight-hour day, a significant improvement in wages and conditions, and the “democratisation of factory life.” In their minds, these were part and parcel of the democratic revolution; they were not seen as a challenge to the capitalist system or to the fundamental rights of private property.25

This reality is well illustrated by the course of the factory committees in the state sector, which was almost entirely war production. The dynamic in these industries were distinctly different from the private sector. With the fall of the tsar, many state enterprises were abandoned by their managers, tied as they were to the old regime. The tsar’s abdication in February left the factories in the hands of “the people.” In this vacuum, workers interpreted this to mean that the factory committees should control all of factory operations. However, as the political situation stabilized, the state reasserted its control, and workers voluntarily returned the reins. One factor that weighed on the consideration of taking full control of production was, as Mandel points out, that “given conditions of economic crisis, the factory committees understood that their chances of failing and being discredited were very great.”26

The fight for the eight-hour day

In many locations following the fall of the tsar, the eight-hour day was simply declared by the committees and immediately implemented. A historian of the factory committees, S. A. Smith, writes that this demand expressed more than the economic needs of the class: “The workers argued that the eight-hour day was necessary not merely to diminish their exploitation, but also to create time for trade union organization, education and involvement in public affairs.”27 Particularly adamant over the introduction of the eight-hour day were women workers. With the double burden of house work and paid work, women workers not only demanded the eight-hour day, but refused to work any overtime, even for time-and-a-half pay.

On March 19, the workers of the Moscow Military-Industry Factory declared, “We consider the establishment of the eight-hour day not only an economic victory but we see it as a fact of enormous political significance in the struggle for the liberation of the working class.”28

In the early weeks of the revolution, with workers on the offensive, the bosses sought to stabilize the situation. Following the de facto implementation of the eight-hour day, the Society of Factory and Works Owners (SFWO) approached the soviet to begin formalizing the relations between employers and employees. On March 10 both sides agreed to three points: recognition of the factory committees, the eight-hour day, and “conciliation chambers” where disputes that could not be worked out on the shop floor could be referred. It would take another month for this agreement to be shaped into a law. On April 23, the Provisional Government issued a law governing factory committees: recognizing them, but in a narrow fashion, reflecting the moderate socialists’ aversion to any talk of “worker’s control.”

“The aim of the government” writes Smith, “as in the legislation on conciliation committees, was not to stifle the factory committees, but to institutionalize them and quell their potential extremism by legitimizing them as representative organs designed to mediate between employers and workers on the shop floor.”29

The law ignored the committees’ incursions into management power: control of the workday and power to hire and fire workers. In this way, the bourgeoisie of Russia in 1917 proved themselves to be the peers of the Western capitalists: attempting to replace direct action with negotiation in order to bring the movement to heel. Despite this, the law spurred the spread of the factory committee movement, and committees appeared in areas of Russia previously unorganized.

Parties and workers’ power

Unlike the soviets, which after 1905 were the subject of intense focus and theorization, the factory committees were not the subject of any serious analysis by any party before 1917. Because of this, members of the various parties followed the general line of their traditions, leading to clashes that would develop into theoretical positions and more explicitly conflicting strategies.

The over-riding fear of the Mensheviks was of fracturing their alliance with the liberal members of the Provisional Government; they counseled their members to seek conciliation rather than conflict. The Menshevik-dominated newspaper of the Soviet, Izvestia, argued, for example, “The wartime situation and the revolution force both sides to exercise extreme caution in utilizing the sharper weapons of class struggle such as strikes and lockouts. These circumstances make it necessary to settle all disputes by means of negotiation and agreement, rather than by open conflict.”30

In late March, the Mensheviks along with the SR’s organized joint factory committee conferences to promote their cautious approach. They convinced participants to forgo intervention in management, and to accept a more limited, union-like role. This success was short-lived, however, and their ability to constrain the impulse to workers’ control declined over the coming weeks. Their returns in committee elections as well as their membership rolls shrank consistently.

The Bolsheviks took more confrontational stances over issues, and openly called for workers’ control. The Bolshevik Party included factory committees and workers’ control in its platform starting in May, and party leaders, including Lenin, wrote articles and theoretical works on the role of the committee movement as it contributed to the struggle for socialism.

In fact, in the first weeks of the revolution some of the factory committees were to the left of even the Bolsheviks’ formal position.31 Calls for the removal of the Provisional Government emerged quite early from shop and factory committees. A resolution from the general assembly of the Nobel Machine-Construction Factory on April 4 illustrates this well:

(1) that the liberation of the working class is the affair of the workers themselves, (2) that the way of the proletariat to its final goal—socialism—lies not on the path of compromises, agreements and reforms, but only through merciless struggle—revolution. . . . (4) that the working class cannot trust any government comprised of bourgeois elements and supported by the bourgeoisie, (5) that our PG, composed almost totally of bourgeois elements cannot be a popular government to which we can entrust our fate and our great victories.32

However, the Bolsheviks quickly caught up following the return of Lenin in April, with a short but sharp debate that aligned the party’s position closely with that of the Nobel workers.

Politics of the factory committee movement

The first phase of the Revolution came to a close in April as class tensions reasserted themselves. The economy, which had initially stabilized, began to falter again and employers began to push back. Small and medium-sized businesses closed their doors, raising fear of retribution and mass unemployment. Factory commitees were finding they could not address the resulting economic chaos from within their factory walls, and began calling for society-wide economic regulation from the Soviet.

Later in April, communications between members of the Kadet Party and their allies exposed their commitment to continuing the war—not just in defense of the revolution until a peace negotiation, but to victory, including annexing new Asian and European territories. An eruption of strikes and protests in response cost the Kadets their posts in the Provisional Government, and moderate socialists joined the government cabinet.

The First Conference of Petrograd Factory Committees, held May 30–June 5, expressed the confidence of the committees, and sharpened the debate on the role of factory committees and the future of economic regulation. Initiated by the Putilov Works committee, 499 delegates attended, representing 337,000 workers from the city and its suburbs. Already, the majority of delegates were Bolsheviks, and over half the total were from the engineering sector. Both Matvey Skobelov, Menshevik minister of labor for the Provisional Government, and Vladimir Lenin of the Bolshevik Party addressed the conference.

The moderate socialists argued that the factory committees were one of a number of grassroots organizations of “toilers” that should work together to regulate the economy, under the leadership of the Provisional Government. They also argued for the absorption of the committees into the unions (where the Mensheviks were still the dominant political force). In essence, the moderate position was to integrate factory committees into the emerging capitalist economy on terms acceptable to the bosses.

In contrast, the Bolsheviks argued that the factory committees should remain independent, and play the majority role (constituting two-thirds of the members) of any regulatory agency. They further argued that economic stability and real regulation could not be achieved without transferring power to the soviets. Under these conditions, workers’ control could become worker management under the auspices of a workers’ state.

Lenin wrote of this question: “In point of fact, the whole question of control boils down to who controls whom, i.e., which class is in control and which is being controlled . . . We must resolutely and irrevocably, not fearing to break with the old, not fearing boldly to build the new, pass to control over the landowners and capitalists by the workers and peasants. And this is what our Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks fear worse than the plague.”33

The Bolshevik resolution won by a landslide, expressing the profound desire of the factory committees to remain independent, and a growing recognition that workplace democracy and the Provisional Government were incompatible.

The Bolsheviks’ resolution on the tasks of the committees were expansive to the extreme: “participation in converting industry to peacetime production; raising productivity; providing fuel, machinery, and raw materials for enterprises; obtaining production orders; supervising the maintenance of adequate sanitary conditions; disciplining workers’ and improving workers’ welfare.”34 They positioned committees to move from holding together workplaces against the chaos of the economy and sabotage of bosses to more consciously and consistently engaging with management and the social issues of production. The conference set up a Central Council of Factory Committees that “was a bulwark of Bolshevism, consisting of nineteen Bolsheviks, two Mensheviks, two SR’s, one Mezhraionets…and one syndicalist.”35

Writing on the wide popularity of the Bolsheviks in the committees, S. A. Smith asserts:

When one examines the debates on workers’ control at these conferences an immediate problem arises, for it emerges that there is no authentic, spontaneous “factory committee” discourse whch can be counterposed to official Bolshevik discourse . . . [M]ost delegates recognized the need for some degree of centralized coordination of control, as the Bolsheviks argued, whereas anarcho-syndicalists decidedly did not. At every conference they voted overwhelmingly for the formula of “state workers’ control.”36

The majority of factory committee delegates were drawn in this quite early stage to the Bolshevik position that linked the demand for workers’ control with centralized planning under a soviet government, and that the factory committees must be linked nationally in a state-wide system. The growth of the membership in the Bolshevik Party was not despite their understanding of the need for a revolutionary reorganization of the economy under Soviet rule—but because of it.

The unions

In February of 1917 only a handful of unions existed in Russia. After a brief period of growth during the 1905 Revolution, they were driven underground and almost entirely eliminated. Police surveillance and persecution kept their formal existence at bay. After 1912 unions began to reemerge under significant Bolshevik influence: of the eighteen unions in Petrograd the Bolsheviks controlled fourteen and the Mensheviks only three (the last was jointly controlled).37 With the outbreak of the revolution in February, the unions expanded dramatically. In the wake of the tsar’s abdication, the Bolsheviks lost their solid majority in the unions, and it would take them until late summer to reclaim their dominant position.

Within two weeks of the tsar’s fall, thirty unions sprang up in Petrograd, initiated by former union members and militants from all political parties in the working class. By the end of April, they numbered seventy-four, and nationally 2,000. By October, two million workers were represented by unions, or about 60 percent of industrial wage-earners. The unions saw their primary tasks as protecting wages and working conditions, as opposed to the factory committees, which intervened directly in production (though clearly their functions overlapped).38

Their creation would have been even more rapid, but unions were not seen as necessary initially given the breadth of factory committee activity. At various times and in many locations, the relationship between the two bodies was contentious. Factory committees, as seen above, had enacted a critical workplace reform—the eight-hour day—which could be either an aspect of production or working conditions. Further complicating the situation were the myriad of different—and sometimes conflicting—methods for organizing unions: single shop, industry type, trade, or even geographic location were all parameters for forming unions. Conflicts over jurisdiction created obstacles to negotiating better conditions.

Efforts to unify the two movements (essentially absorbing the factory committees into the union structures) stalled on the obvious friction between the moderates, who were propping up the Provisional Government, and the Bolsheviks, who sought to overthrow it. The unions, while enormously popular, did not have the day-to-day contact or the active participation of members that factory committee members did; the factory committees (with their subcommittes on security, meals, and theater clubs) permeated workplace life, drawing in a larger number of active participants in their multilayered structures.

Labor organizations in tsarist Russia had always sought to coordinate and form national links. On March 3—eight days into the revolution—union representatives in Moscow reestablished their citywide union bureau. Shortly after, Petrograd union organizers formed the Petrograd Trade Union Council, which by May represented 50 percent of the city’s workers.39

On March 15 the Petrograd Trade Union Council announced its views on the best means to organize unions: “Unions should be organized by industries, [any] divisions by trades are harmful.”40 Mergers were facilitated that eased the organization of large-scale negotiations. The Third All-Russian Trade Union Conference, held June 20–28, similarly adopted a position on merging smaller craft units. Consolidation across the labor movement moved rapidly: by the fall of 1917, as membership hit two million, the number of individual unions fell by half.

While moderate socialists initially dominated the union movement, unions in Russia were far more radical than the older, more established movements in the US or Europe. Reformism was weaker

for the simple reason that even the most “bread and butter” trade union struggles foundered on the rock of the tsarist state; all efforts to separate trade unionism from politics were rendered nugatory by the action of police and troops. In this particular climate trade unions grew up fully conscious of the fact that the overthrow of the autocracy was a basic precondition for the improvement of the workers’ lot.41

Accepting the need to overthrow the tsar made the union movement fertile ground for socialists of all stripes. Conflicting visions for the workers’ movement after the overthrow of the tsar played out inside the unions. The moderates’ and the Bolsheviks’ differing perspectives dominated discussion at the Third All-Russian Trade Union Conference around two key issues: the war and the use of strikes.

Moderates within the union movement sought to keep bread and butter issues separate from the simmering political crisis. The moderate socialists unionists were called “neutralist” for their resistance to taking a position on the war. They hoped that workers’ struggles would be constrained by the economic pressures and chaos created by war. The Bolsheviks led the “internationalist” camp. Their resolution on union work declared:

The working class is entering a terrain with vast social horizons, which culminate in world socialist revolution. The trade unions are faced with the completely practical task of leading the proletariat in this mighty battle. Together with the political organization of the working class, the trade unions must repudiate a neutral stance toward the issues on which the world labor movement now hangs. In the historic quarrel between “internationalism” and “defensism” the trade-union movement must stand decisively and unwaveringly on the side of revolutionary internationalism.42

The “internationalist” resolution failed to win the majority of trade union delegates at the First Conference—including many who were not aligned with any of the major parties. Their overriding concern was for unions to focus on practical activity. This did not indicate the dominance of prowar sentiment; instead it reflected the hope that the soviet, rather than the unions would win the Provisional Government off its pro-war course.

The second divisive issue within the union movement was around the question of strikes. Here again the Menshevik perspective—that workers should constrain their militancy so as not to drive the bourgeoisie into the arms of reaction—undermined their ties to workers. The moderates argued for cooperation with the Soviet Executive Committee to mediate class conflict. Negotiation, not confrontation, was their watchword.

But ironically, here again practical questions were in the forefront of delegates’ minds, this time pulling them behind the Bolshevik platform. The Bolsheviks argued that in a revolutionary epoch, strikes were the most important weapon for workers. Having just overthrown a centuries-old monarchy through strike action, and harboring a deep distrust of managers, union members were unwilling to stop striking in the interest of political coalition with the bosses’ representatives.43 The April legislation had included conciliation chambers, but these had turned out to be toothless in addressing workers’ demands. The spring had proven that the Provisional Government would not intervene on behalf of workers to enforce its own laws, leaving workers to draw the conclusion that direct action was the only means to achieve their aims.

Shkliarevsky comments on the conflicting results of the Third All-Russian Trade Union Conference:

While rejecting the antagonistic attitude toward the Provisional Government, it advocated a confrontational approach vis-à-vis employers. Implicit in this course was the notion that political issues and labor issues per se could be effectively dissociated. The fact of the matter was that they were intimately interrelated: strikes certainly destabilized the political and economic order and thus undermined the position of the government. Reliance on strikes as their chief weapon was certainly a confrontational approach that could bring the unions into conflict with the government.44

Polarization between the classes paralyzed the political process; coalition was less and less practicable. Legislation crawled into existence lagging behind events, and enforcement was all but impossible. The inability of the Provisional Government and the Soviet Central Executive Council to ensure improvements for working people eroded confidence in the government and discouraged support for the moderate socialists who preached support for coalition.

By June, the Bolsheviks held majorities in most major union boards and, together with the Menshevik Internationalists, dominated the Petrograd Central Trade Union Council board. However, one must not oversimplify the meaning of the rise of Bolshevik influence in the unions in June. The Bolshevik cadre in the unions held very narrow majorities and worked very closely with Menshevik-Internationalists to craft compromise resolutions and strategy within the Petrograd Central Trade Union Council, which had a conservatizing effect. Furthermore, most of the day-to-day work of the unions was in fact directed around immediate workplace issues, so the conflicting positions on larger social questions between Menshevik and Bolshevik were often sidelined. Within the Bolsheviks themselves, debate lingered over the course of the revolution, and the worker-cadre within the union movement tended to be less critical of the moderates and their course than their comrades in the factory committees.

The wage struggle

The gargantuan inflation that gripped Russia during the war drove the ongoing battles over wage rates. By one estimate, the cost of living in Petrograd by October 1917 had risen by 14.3 times its prewar level.45 Striking was the most common response, and workers who had struck to bring down the tsar were confident in the strike weapon to bring redress. Diane P. Koenker and William G. Rosenberg calculate that between March and late October there were 1,019 strikes, involving more than 2.4 millions workers.46

However, as the spring wore on, partial and local strikes were losing their effectiveness. Wage gains were eaten up by inflation as soon as contracts were settled, and bosses were more likely to resist than in the earlier stage of the revolution. Union activists had been studying the wage issue since the fall of the tsar, and by summer the need for stronger redress was obvious. Only through industry-wide, or legislative change, could starvation conditions be addressed adequately.

This trajectory was urged on by two factors. First, frustration that things were not changing fast enough, or were even getting worse after February, gripped the class. Petrograd’s woodworkers’ union sent out a survey about what the Revolution had achieved; answers that came back included: “nothing,” “nothing special,” “nothing, but management is better,” and “nothing has changed.” Only half bothered to return their forms. All of the positive achievements listed were the results of factory committees. These questionaires expressed the anger of the slow pace of change paired with a recognition that only self-activity had brought measurable results.47

Secondly, new layers of workers—largely unskilled and previously unorganized—moved into struggle. Most of the leadership of unions and committees arose from the skilled workers, who were on par with their European counterparts in terms of literacy and education. These “cadre” workers were surrounded by droves of “black workers” (chernorabotsie), the more recent transplants from the country who toiled in slave-like conditions of physical labor. The gap between the wages of the skilled and the unskilled was large: skilled workers making sometimes double what the unskilled earned.

Both of the factors above contributed to the central struggle of the summer in Petrograd: the Metal Workers’ Union (MWU) wage negotiations. The three key demands put forth were: an end to piece-rates, sizeable raises, and a closing of the gap between skilled and unskilled workers. It is a noteable testimony to the state of class consciousness that the more organized, more experienced cadre workers who formed the backbone of the unions put the closing of the wage gap at the center of the struggle. In effect they were arguing for greater improvements for the less organized sections than they asked for themselves.

Meanwhile, the unskilled at Putilov initiated their own organizing, including an abortive strike in early June. They reached out to other unskilled workers, creating new networks of the unskilled across the metal working sector. Tension simmered between the unskilled workers, desparate for more immediate change, and the leadership of the union who were seeking a larger scale solution.

The board of the largest and most pivotal union, the metal workers union, issued the following statement expressing their frustration at the lack coordination dogging the movement in early June:

Instead of organization, we, unfortunately now see chaos . . . instead of discipline and solidarity—fragmented actions. Today one factory acts, tomorrow another and the day after that the first factory strikes again—in order to catch up with the second . . . The raising of demands is often done without any prior preparation, sometimes by-passing the elected factory committee. The metalworkers’ union is informed about factory conflicts only after demands have been put to management, and when both sides are already in a state of war. The demands themselves are distinguished by lack of consistencey and uniformity.48

The MWU undertook to negotiate new industry-wide wage scales with the Society of Factory and Works Owners (SFWO) in late June. Works committees representing seventy-three factories, union delegates, and representatives from the socialist parties met and agreed to a general strike if the union negotiations failed.

In the midst of the negotiations, Petrograd exploded in armed demonstrations. The Soviet had attempted to mobilize the Second Machine Gun Regiment to the front to join the doomed military offensive launched in June, but was openly disobeyed. Bolsheviks in the garrison supported their disobedience, and the gunners heightened the crisis by marching factory to factory, calling out workers to strike and demonstrate. Wave after wave of workers angry over the government’s foot-dragging on wage increases flooded the streets in a general strike.

While targeting the Provisional Government, the July Days—as this revolt came to be known—expressed the ambivalence workers had toward the moderate socialists who still dominated the Soviet Executive Committee and many local soviets. Reacting to the Soviet’s refusal to take power and its branding of demonstrators as “counter-revolutionary,” a worker-representative chosen to address the Executive Committee laid out the sentiment of many revolutionary workers: “Our demand—the general demand of the workers—is all power to the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies . . . We trust the Soviet, but not those whom the Soviet trusts.”49

The July Days exhausted itself, venting the frustration and impatience felt by Petrograd’s workers and soldiers, led in many cases on the ground by Bolshevik activists in the party’s military organization. The Bolshevik leadership, despite preaching calm and restraining the movement, was viciously targeted by the Provisional Government; the party’s headquarters were raided, its presses smashed, and its leaders arrested or forced into hiding. But after a few weeks it became clear that the danger of a preemptive attempt at seizing power in July had passed with minimal damage to the workers’ movement.

The MWU contract was settled in mid-July. When the SFWO refused to accept the full wage increases for the unskilled workers, the union delegates quickly moved to prepare a strike. Cautious that a renewed struggle only weeks after the July Days would bring down the full weight of government repression, union leaders, including Bolsheviks, accepted a controversial compromise.

The overall gains of the contract were considerable, but raises for the unskilled workers fell 10 to 15 percent short of the union’s demands. These workers vented their bitter disappointment at the union leaders, but the greater part of their anger was directed at the government for failing to intervene on their side. For the previously apolitical layer of workers the compromise had the unintended consequence of driving home the impossibility of deeper change under the Provisional Government. A Putilov worker quoted in Prava said, “We have seen with our own eyes . . . how the present Provisional Government refuses to take resolute measures against the capitalists, without which our demands cannot be satisfied. The interests of the capitalists are dearer to it than the interests of the working class.”50

As the summer drew to a close, the inevitable conclusion hundreds of thousands of workers were drawing was that without establishing a new political system, even the most basic economic demands could not be met. The optimism of March had given way to a hardened resolve to make good on the promises of the February Revolution by the only apparent means available: overthrowing the Provisional Government and placing all power in the hands of the soviets. The material gains of the wage struggle—substantial as they were—are overshadowed by their political implications.

Shkliarevsky writes:

Strikes were a politicizing experience for those who took part in them: they saw with their own eyes how employers were going on investment strike, engaging in lockouts, refusing to accept new contracts or to repair plants; how the government was colluding with the employers, curbing the factory committees and sending troops to quell disorder . . . The strikes were important therefore, in making hundreds and thousands of workers aware of political matters and in making the policies of the Bolshevik party attractive to them.51

Polarization and reaction

As the summer came to an end, the workers’ movement consolidated organizationally, and incursions on ruling-class power were becoming more political and more generalized. The Provisional Government understood its grasp on power was slipping. In this precarious situation, the capitalist politicians sought to reestablish control by undermining the movement at its foundations. As Shkliarevsky writes, “It had to discipline the factory committees and make them obey the law.”52

Managers had been attempting to undermine the factory committees without directly confronting them: refusing to pay workers for time in committee meetings, and threatening members with firing or the draft. In August the government took more open action. The Menshevik Labor Minister M. I. Skobelev issued two circulars: the first on August 22 affirmed management’s power to hire and fire workers, a key role played by factory committees. The second, published on August 28, decreed that factory committee meetings could not be held during work hours or on work premises, without the express permission of the bosses. At the same time, the bosses and Provisional Government attempted to disarm Red Guards, although neither had the means to effectively challenge armed workers.

The Skobelev circulars were to be a dead letter, washed away in a new demonstration of working-class strength. The President of the Soviet Central Executive Committee, Alexander Kerensky, provoked a massive outpouring of worker activity by attempting to allow a military occupation of Petrograd. Kerensky had negotiated the occupation with Lavr Kornilov, stalwart reactionary supreme commander of the Russian Army. In Kerensky’s fantastical interpretation of this agreement, Kornilov would install him as the head of the coming dictatorship.

But upon the commencement of the plan, it became evident that Kerensky himself would be pushed aside by Kornilov. Making a 180-degree turn, Kerensky called for defense of the government against the approaching military. Unfortunately for him, the only forces able to disperse the coming occupation were the mutinous army and armed workers, under the leadership of the factory committees, the unions, the Red Guards, and the Bolsheviks.

The anti-Kornilov mobilization drew out hundreds of thousands of workers and soldiers. The leadership role of the factory committees, Red Guards, and Bolsheviks is well documented; but unlike the July Days, which largely passed the unions by, the latter played a much more active role. The attempts to segregate the “purely economic” struggle from the political struggle were falling apart as the classes squared off against one another. Kornilov’s offensive melted away in the face of mass mobilization, made possible by the criss-crossing networks of workers’ and solders’ organizations.

Understanding the necessity of clearing away the obstacle of the Provisional Government to allow the Soviet to assume power, workers joined the one party that put this at the center of its strategy: the Bolsheviks. Leon Trotsky’s Petrograd-based Interdistrict Organization (Mezhraiontsy) fused with the Bolsheviks as well, bringing in 4,000 active members. By September 1st, 126 local soviets demanded a transfer of power to the Soviet. In the same period city-wide soviets in Petrograd, Moscow, Ivanovo- Voznesensk, Kronstadt, and Krasnoyarsk passed resolutions in support of the Bolshevik Party, delivering embarrassing defeats to Mensheviks attempting to block them.53

Debates between comrades

Tensions between the factory committees and the unions were rife within the movement throughout 1917. At times their competing efforts to resolve the same issue in the same workplace caused clashes. In the abstract it may have made sense for the unions and factory committees to fuse to avoid redundancies and squabbling. The incorporation of the committees into the unions as subordinate bodies would have brought the better organized, more radical workers in the factory committee movement under the wing of the moderates, and by extension, the Provisional Government. But as more workers demanded “All Power to the Soviet”, unions moved left and drew closer to the factory committees.

As the Bolshevik Party grew numerically, it recruited unaffiliated activists as well as the cadre of rival parties, introducing more diverse perspectives. In addition, even its long-term cadre, rooted in workplaces and neighborhoods, took differing positions on strategic questions depending on their locations.

One such debate in the summer of 1917 was over the role of the factory committees in the revolutionary process, especially regulation. As shown above, this mirrored the debate within the larger movement—although both sides within the Bolsheviks accepted the necessity of revolution. The radical position within the Bolshevik Party, articulated by Pavel Amosov, identified ruling-class treachery as the key source of chaos in the economy. To stabilize the economy, the factory committees therefore needed to expand their centralization and coordination to overcome bourgeois resistance. The routing of the Kornilov Coup was in part because the committees had stretched themselves, investing further into the Red Guards and asserting themselves beyond the factory gates. In addition, workers’ control had, in some instances, been able to halt factory closures through the initiave of subcommittees locating raw materials, or even securing loans from other factory committees.

The moderate Bolsheviks, like Central Committee member Vladimir Miliutin and railway union founder David Riazonov, placed heavier emphasis on the objective conditions of the economy: its low level of productivity (which predated the Revolution), lack of resources and fuel, and the impending collapse of sectors like transport. Better committee coordination alone, they argued, could not solve the problems facing the economy.

The radicals also argued that the factory committee was the key vehicle for the coming revolution. In contrast, the “moderate” comrades saw the soviets and the unions as the more effective vehicles to challenge bourgeois rule. Needless to say, many of the moderates were themselves union members or union leaders, or were delegates in a soviet. These positions correlated with projections of when full centralization could happen—the radical Bolsheviks argued that factory committees could overcome ruling-class resistance even before the transfer of power to the Soviet.

The moderates within the Bolsheviks ultimately won the argument that Soviet regulation must be established to overcome the crisis in the economy. The bourgeoisie could not be economically dethroned while still holding political power. The radicals’ downplaying of the role of the Soviet was an expression of frustration over the continued dominance of the Mensheviks and SR’s. The Soviet was seen as compromised and unable to enact a socialist agenda. Lenin himself briefly—during the crackdown following the July Days—entertained the idea that the soviets had become so conservative that the factory committees were a more suitable vehicle to organize the seizure of power.

This debate over economic regulation dovetails with another critical question arising in October over the nature of the insurrection and who would rule in its aftermath. While the factory committees were purely workers’ bodies, the soviets had grown to be inclusive of soldiers, sailors, peasants, and workers. The unique position of the workers as direct producers makes it the critical actor in rebuilding an economy based on human need; however the process of making a revolution in Russia relied on the fusion of different exploited classes and the Soviet was where that fusion existed. In this way, the working class was able to leverage its power, despite its small size, relative to the peasantry.

Revolution and workers’ power

The closing of summer and onset of fall saw a significant growth and consolidation of revolutionary sentiment. The repulsion of Kornilov left the Soviet exposed and the Provisional Government deflated. With a last gasp, the Provisional Government organized a Democratic Conference in September as an attempt to revitalize a coalition government in the eyes of the public. Their effort collapsed leaving the Provisional Government dead in the water.

As October unfolded, the Provisional Government’s control over the military forces in Petrograd eroded further. The government’s attacks on workers and soldiers won the Bolshevik leaders of the Petrograd Soviet support to form the Revolutionary Military Committee. The Provisional Government moved to crush this new body of revolutionary soldiers and workers. It ordered the Petrograd garrison to disarm the Revolutionary Military Committee and attack the Bolsheviks’ headquarters. But the garrison itself had already been largely won to the revolutionaries’ side. The Bolsheviks’ momentum in the ensuing conflict led to the arrest of the Provisional Government. The All-Russian Soviet solidified the overthrow of the government by voting to transfer all power to the soviets: after months of working class calls to take power, the revolution had triumphed.

Although the dissolution of the Provisional Government led to the consolidation of a worker and peasant government (with an alliance of Bolsheviks and Left SR’s at its helm), it simultaneously unleashed a new wave of heightened class struggle and chaos. Eyewitness and anarchist-turned-Bolshevik Victor Serge described the immediate aftermath of the revolution:

This rational form of progress toward socialism was not at all to the taste of the employers, who were still confident in their own strength and convinced that it was impossible for the proletariat to keep its power. The innumerable conflicts that had gone on before October now multiplied, and indeed became more serious as the combativity of the contestants was everywhere greater.54

The spike in employer resistance became the impetus for a more thorough seizure of control in the workplace. The initial draft for a Decree of Workers Control, written by the All-Russian Council of Factory Committees, only dealt with creating a state-sponsored apparatus to regulate the economy, and did not speak to the issue of worker control. Lenin himself criticized the document, and insisted on the inclusion of the right of workers to control production, have access to all financial records and accounts, and oversee the committee system from the bottom up. “This awkward fact makes nonsense the claim in Western historiography,” argues Smith, “that, once power was in his grasp, Lenin, the stop-at-nothing centralizer, proceeded to crush the ‘syndicalist’ factory committees. In fact, the reverse is true.”55

After the October Revolution, Lenin wrote:

Vital creativity of the masses—that is the fundamental factor in the new society. Let the workers take on the creation of workers’ control in their works and factories, let them supply the countryside with manufactured goods in exchange for bread . . . Socialism is not created by orders from on high. Its spirit is alien to state-bureaucratic automatism. Socialism is vital and creative, it is the creation of the popular masses themselves.56

In the months immediately following the insurrection, Bolshevik policy optimistically oriented on self-activity. There were debates about the degree of incursions into the control bosses exercised, but the pressures of the moment soon eclipsed these debates. The economy the soviet system inherited was wrecked and further declined in the heat of bourgeois resistance and armed counterrevolution. The articulated policy of the new state was bottom-up regulation of industry under the auspices of the newly formed Supreme Council of the National Economy, combined with nationalization of first the banks, and eventually other industries. Contrary to hysterical accounts of Bolshevik terror, the party did not intend for immediate displacement of owners and managers—even in the more radical interpretation of “workers control.”

Understanding the weak industrial base and isolated position of the working class in a sea of over 100 million peasants, the Bolsheviks aimed for economic stability as much as possible, by allowing a continued mixed economy of state ownership, state regulation, and private ownership. But in the conditions of sabotage and lockout the ex-rulers unleashed, factory committees seized workplaces, seeking greater and greater intervention on the part of the state. Nationalization accelerated and the balance shifted more toward the apparatus and away from local control. Ironically it was the factory committee’s themselves who pressed most adamantly for the policy of nationalization; on June 28, 1918 they got their wish when the wholesale nationalization of all industries was announced.

During the same period factory committees and unions underwent a radical change in their relationship. While pre-revolution there had been some chafing over what role each would play,57 by summer 1917 it had become clear that the unions acted primarily to protect wages amd conditions, while the factory committees oversaw production. Their relationship to their membership was different—factory committees were the most grassroots organs. But they were limited by their focus on a single workplace, no matter how large. Unions, though not as directly in touch with the rank and file, spanned whole industries.

Moderate Bolsheviks, along with allies from other socialist parties, argued that the factory committees should be subordinated to the unions, and act as their basic cells. Before October, the factory committees were hostile to this proposal, but over time the two organizations drew nearer, and many leaders softened to the idea. With the transfer of power to the Soviet, the Bolsheviks reassessed the role of the unions. Since the state was now the most powerful body protecting the working conditions and wages of the working class, the unions were now needed to raise economic regulation from the level of the individual shop to entire industries. After some clumsy negotiations, during which the moderate Bolshevik Riazonov asked the factory committees to “choose that form of suicide which would be most useful to the labor movement as a whole,”58 the factory committees agreed to be subordinated to the unions. The First All-Russian Congress of Trade Unions, where this relationship was formally adopted in January 1918, included the presence of Menshevik delegates who supported the Bolshevik resolution for unity.

In reality, the fusion of the factory committees and unions would not prove to be effective. The unions did not facilitate the inclusion of the vast networks of factory committees into their own apparatus, and the factory committees were far more skilled at the kind of intervention the unions were seeking to undertake. In practice, the factory committees continued to dominate life in the factories, and exercised a great deal of independence.

As civil war consumed Russian society, pressures mounted to consolidate power as quickly as possible. The preservation of the fledgling workers’ state was the top priority; all other concerns were downgraded. The Bolsheviks were painfully aware of the retreats they were making on some of the revolution’s social goals; they were given little room to maneuver, however, in the face of the dual threats of counterrevolutionary White armies and direct imperialist intervention. Alongside the rise of international solidarity and attempted revolutions that the Russian example inspired, the Bolsheviks faced military intervention from Germany as well as more than a dozen Allied Powers. A stranded island of workers’ power, the revolutionary government sought first and foremost to survive until the next workers’ revolution broke out.

This never materialized, despite several short-lived uprisings in Bavaria, Italy, Finland, Poland, and Hungary in the following three years (and others within the next ten). The Bolshevik understanding of the Russian Revolution was that it could initiate, but not complete, an international transformation from capitalism to socialism. Before 1925, the idea of stand-alone socialism in Russia was unknown among Russian Marxists. While the Bolsheviks had the audacity to initiate the process, they lacked the material basis to complete it.

The economy, already in shambles, went into utter free fall during the civil war. As the material basis of capitalist production collapsed, so did the class itself. Food production declined dramatically, producing widespread famine. The working class, reduced to 43 percent of its former size, produced an industrial output of 18 percent of its prewar amount. With this disintegration of the class that made the revolution came a increasing centralization from above to win the civil war as democratic control atrophied from below.59

Smith’s description of the decline in material conditions and democracy captures this history:

After October the Bolshevik leaders of the factory committees, sincerely committed to workers’ democracy, but losing their working class base, began to concentrate power in their hands, excluding the masses from information and decision-making and set up a hierarchy of functions. The trade unions too, became less accountable to their members, since they were now accountable to the government, and soon turned primarily into economic apparatuses of the state. This may all suggest that bureaucratization was inscribed in the revolutionary process in 1917, but if so, it was inscribed as a possibility only . . . Democratic and bureaucratic elements existed in a determinate relationship in all popular organizations—a relationship which was basically determined by the goals of the organizations and the degree to which those goals were facilitated by political and economic circumstances. These circumstances were to change dramatically in the autumn of 1917, and it was this change which shifted the balance between forces of democracy and bureaucracy in favor of the latter.60

Conclusion

There is no more brilliant example of the capacity of workers to politically conceive and organize a different kind of world than the Russian Revolution. The Russian factory committees’ breadth and ingenuity, their ability to draw wide numbers of unaffiliated workers into the practical work of maintaining production, and their flexibility in growing with the revolution into organs of self-management are a high standard for struggling workers to look to for inspiration. Similarly the industrial unions that drew members with the most basic understanding of organization into titanic battles against Russian capital and the state provided the ground for the mass shift in revolutionary consciousness among all layers of the working class.

It was through the lived experience and hard trials of struggle that workers internalized the political ideas of the Bolshevik Party. In turn, the initiative of the working class pushed the Party to absorb, distill, and debate the ever-changing conditions within the workplaces. The infrastructure for struggle that was built through the committees and the unions had the potential, along with the system of soviets, to present an existential challenge to Russian capitalism. But their victory was in no way inevitable. The inspiring efforts of the working class could have been dispersed, disorganized, or crushed in 1917 if not for the presence of the Bolsheviks.

Trying to read backwards from the bureaucratic nightmare of Stalinism into the efforts of the Bolsheviks in 1917 means a willful denial of the well-chronicled, productive, and democratizing impact of Bolshevik activists. Their collective discipline and centralized approach to strategy provided them the insight of when to fight for industrial, rather than sectional, gains; their flexibility allowed them to integrate the committees into the very heart of their understanding of the economy of a new workers’ state.

Given the profound diversity of organizations workers utilized in 1917, as well as the other centers of radicalism (the soldiers and sailors most obviously), and the variant moods and experiences they encompassed, it is surprising the Bolsheviks held together at all. Instead of fracturing, the Party provided a grounding center for all of these threads to wind together.

Understanding this in no way demands of the modern socialist an uncritical acceptance of every action or policy of the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks never demanded this of their own membership (until the Stalinist counterrevolution), and hopefully the debates described above show some of the vibrancy of the internal life of the Party. It is difficult to comprehend how this flowering of democracy quickly transformed into the horrors that were unleashed during the civil war: famine, state terror, and grain requisitioning. The erosion of workplace democracy and even the suppression of strikes were unforeseen developments forced on the new Soviet administration by conditions of desperation and the failure of revolution to spread. It is hard to understand, but it is not impossible to see how this contradiction unfolded, against every intention of the party that led a revolution introducing the widest democracy the world has known.

In conditions of isolation the Bolsheviks were unable to preserve the reality of workers’ control and management. Its legacy has been buried for decades under the filth of Stalinism. But thanks to the efforts of academics unearthing the troves of documentation from unions, soviets, and committees, today’s generation of Marxists can study the lessons and achievements of the Russian revolutionary workers’ movement. This rich history is our inheritance, to be studied, but more importantly to be used in our own future struggles.

- Quoted in S.A. Smith, Red Petrograd (London: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 81.

- Rosa Luxemburg, “Our Program and the Political Situation,” (December 1918). https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxembu....

- Maurice Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers Control (Detroit: Black & Red, 1975). http://spunk.org/texts/places/russia/sp0.... While Brinton’s conclusions are starkly opposed to the views of this author, his work is a veritable treasure trove of research.

- Noam Chomsky, “Socialism Versus the Soviet Union”, Our Generation, Spring/Summer 1986. https://chomsky.info/1986____/.

- Nikolai Suhkanov, The Russian Revolution, 1917: A Personal Record (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 529.

- The Socialist Revolutionary Party of Russia inherited the political legacy of peasant radicalism embodied in the Narodnik movement of the late nineteenth century. The party was made up of a combination of urban and rural petit bourgeois leadership and a mass membership of industrial and rural laborers. The peasant tradition of radical anti-authoritarian acts, including terrorism, persisted (and would blossom again in dramatic form against the Bolsheviks after October), and the party shared the Menshevik belief that the next stage of Russian society must be capitalist.

- This small grouping based in Petrograd had formed around a nucleus of former Bolsheviks and stood politically between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. It was most notable for the leadership of Leon Trotsky, but other formidable Marxists were members: Adolf Joffe, Anatoly Luncharsky, Moisei Uritsky, David Riazanov, and one of the greatest worker-orators of the revolution: V. Volodarsky.

- John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World (New York: International Publishers, 1967), 14–15. https://www.marxists.org/archive/reed/1919/10days/10days/.

- David Mandel, Factory Committees and Workers’ Control in Petrograd, International Insitute for Research and Education, Number 21, 1993, 2.

- A word on what this article won’t take up. It may seem strange in an article about workers’ organization to not describe the soviets themselves. This is in part because the soviets are already given the place of pride in the history of the Revolution of 1917 and are well documented. The soviets also grew to encompass almost every disgruntled segment of society, whereas the unions and factory committees were centered on the workplace and largely on workplace issues (although they took an expansive view of what that meant). Further, in some smaller localities, factory committees and soviets were one and the same body for much, if not all, of the Revolution. The other significant missing piece is the Red Guards. The Guards constituted armed units from the major factories and provided security against counter-revolutionary threats. While they expressed the same impulse to self-organization and direct democracy as shop-floor groups, and their presence could at times allow the shop-floor movement to advance, they were not one of the means that workers engaged with economic issues of control and production.

- An elaboration of this can be found in the first chapter of Leon Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017).

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 9–10.

- Figures are taken from V. I. Lenin, “Strike Statistics in Russia,” (1910) Collected Works Vol. 16 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974), 395.

- Victoria E. Bonnell, The Roots of Rebellion: Workers’ Politics and Organizations in St. Petersburg and Moscow 1900–1914 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983), 171–80.

- Robert B. McKean, St. Petersburg Between the Revolutions: Workers and Revolutionaries, June 1907–February 1917 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 406.

- Diane Koenker and William Rosenberg, Strikes and Revolution in Russia, 1917 (Princeton, 1989), 66.

- Gennady Schkliarevsky, Labor in the Russian Revolution: Factory Committees and Trade Unions, 1917–1918 (New York: St. Martins Press, 1993), 3.

- Ibid., 4.

- John Reed, Ten Days That Shook The World (New York: International Publishers, 1967), 14–15. https://www.marxists.org/archive/reed/1919/10days/10days/.

- David Mandel, Factory Committees and Workers’ Power in Petrograd in 1917 (International Institute for Research and Education, Notebooks for Study and Research Number 21, 1993), 15–16.

- Ibid., 160–61.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 82.

- Ibid., 85.

- David Mandel, Factory Committees and Workers’ Power in Petrograd in 1917.

- David Mandel, Petrograd Workers and the Fall of the Old Regime, Volume 1: From the February Revolution to the July Days (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 1983), 105. http://classiques.uqac.ca/contemporains/....

- Mandel, Petrograd Workers Vol. 1, 129.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 65–6.

- Mandel, Petrograd Workers Vol. 1, 106.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 79.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 77.

- Within the party multiple positions existed on the development of the revolution, some calling for the elimination of the Provisional Government and establishment of a radical democracy of the exploited, and others adhering to the older formulation of a western-style democracy. See Paul D’Amato: “How Lenin Rearmed,” International Socialist Review, Number 106 (Summer 2017).

- Mandel, Petrograd Workers, Vol. 1, 88–89.

- Lenin, “the Impending Catastrophe and How to Combat It,” Collected Works, Vol. 25 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1980), 346.

- Shkliarevsky, Labor in the Russian Revolution, 28–29.

- Ibid., 82.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 156–57.

- Tony Cliff, Building the Party (London: Bookmarks, 1982), 331-32. https://www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/w....

- Shkliarevsky, Labor in the Russian Revolution, 66–67.

- Ibid., 67.

- Ibid., 70.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 109–10.

- Quoted in Ibid., 110.

- While SFWO and their political allies among the liberals sought stability, their version rested on emiseration and disciplining the working class, not sharing the wealth.

- Shkliarevsky, Labor in the Russian Revolution, 79.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 116.

- Koenker and Rosenberg, Strikes and Revolution in Russia, 1917 (Princeton, 1989).

- Ibid., 116.

- Quoted in Smith, Red Petrograd, 120.

- S.A. Smith, The Workers’ Revolution in Russia, 1917, ed. Daniel H. Kaiser (Cambridge University Press, 1987) 69.

- Quoted in Smith, Red Petrograd, 125.

- Ibid., 118.

- Shkliarevsky, Labor in the Russian Revolution, 51.

- The polarization of Russian society included a massive wave of peasant revolts, wherein lords’ lands were seized and manors burned to the ground. Within the main peasant party, the Socialist Revolutionaries, a left-wing current crystalized and began operating independently. The Left SR’s blocked with the Bolsheviks in calling for an end to the Provisional Government and immediate end to the war. The Bolsheviks in turn adopted the Left SR’s platform of immediate land reform in the countryside. They would be coalition partners following the October Revolution until March 1918 when peace with Germany was concluded at Brest-Litovsk.

- Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution, 136.

- Smith, Red Petrograd, 210.

- Quoted in Ibid., 156.