By Julian Baggini and Lawrence Krauss, The Guardian, September 9, 2017

Julian Baggini No one who has understood even a fraction of what science has told us about the universe can fail to be in awe of both the cosmos and of science. When physics is compared with the humanities and social sciences, it is easy for the scientists to feel smug and the rest of us to feel somewhat envious. Philosophers, in particular, can suffer from lab-coat envy. If only our achievements were so clear and indisputable! How wonderful it would be to be free from the duty of constantly justifying the value of your discipline.

However – and I'm sure you could see a "but" coming – I do wonder whether science hasn't suffered from a little mission creep of late. Not content with having achieved so much, some scientists want to take over the domain of other disciplines.

I don't feel proprietorial about the problems of philosophy. History has taught us that many philosophical issues can grow up, leave home and live elsewhere. Science was once natural philosophy and psychology sat alongside metaphysics. But there are some issues of human existence that just aren't scientific. I cannot see how mere facts could ever settle the issue of what is morally right or wrong, for example.

Some of the things you have said and written suggest that you share some of the science's imperialist ambitions. So tell me, how far do you think science can and should offer answers to the questions that are still considered the domain of philosophy?

Lawrence Krauss Thanks for the kind words about science and your generous attitude. As for your "but" and your sense of my imperialist ambitions, I don't see it as imperialism at all. It's merely distinguishing between questions that are answerable and those that aren't. To first approximation, all the answerable ones end up moving into the domain of empirical knowledge, aka science.

Getting to your question of morality, for example, science provides the basis for moral decisions, which are sensible only if they are based on reason, which is itself based on empirical evidence. Without some knowledge of the consequences of actions, which must be based on empirical evidence, then I think "reason" alone is impotent. If I don't know what my actions will produce, then I cannot make a sensible decision about whether they are moral or not. Ultimately, I think our understanding of neurobiology and evolutionary biology and psychology will reduce our understanding of morality to some well-defined biological constructs.

The chief philosophical questions that do grow up are those that leave home. This is particularly relevant in physics and cosmology. Vague philosophical debates about cause and effect, and something and nothing, for example – which I have had to deal with since my new book appeared – are very good examples of this. One can debate until one is blue in the face what the meaning of "non-existence" is, but while that may be an interesting philosophical question, it is really quite impotent, I would argue. It doesn't give any insight into how things actually might arise and evolve, which is really what interests me.

JB I've got more sympathy with your position than you might expect. I agree that many traditional questions of metaphysics are now best approached by scientists and you do a brilliant job of arguing that "why is there something rather than nothing?" is one of them. But we are missing something if we say, as you do, that the "chief philosophical questions that do grow up are those that leave home". I think you say this because you endorse a principle that the key distinction is between empirical questions that are answerable and non-empirical ones that aren't.

My contention is that the chief philosophical questions are those that grow up without leaving home, important questions that remain unanswered when all the facts are in. Moral questions are the prime example. No factual discovery could ever settle a question of right or wrong. But that does not mean that moral questions are empty questions or pseudo-questions. We can think better about them and can even have more informed debates by learning new facts. What we conclude about animal ethics, for example, has changed as we have learned more about non-human cognition.

What is disparagingly called scientism insists that, if a question isn't amenable to scientific solution, it is not a serious question at all. I would reply that it is an ineliminable feature of human life that we are confronted with many issues that are not scientifically tractable, but we can grapple with them, understand them as best we can and we can do this with some rigour and seriousness of mind.

It sounds to me as though you might not accept this and endorse the scientistic point of view. Is that right?

LK In fact, I've got more sympathy with your position than you might expect. I do think philosophical discussions can inform decision-making in many important ways, by allowing reflections on facts, but that ultimately the only source of facts is via empirical exploration. And I agree with you that there are many features of human life for which decisions are required on issues that are not scientifically tractable. Human affairs and human beings are far too messy for reason alone, and even empirical evidence, to guide us at all stages. I have said I think Lewis Carroll was correct when suggesting, via Alice, the need to believe several impossible things before breakfast. We all do it every day in order to get out of bed – perhaps that we like our jobs, or our spouses, or ourselves for that matter.

Where I might disagree is the extent to which this remains time-invariant. What is not scientifically tractable today may be so tomorrow. We don't know where the insights will come from, but that is what makes the voyage of discovery so interesting. And I do think factual discoveries can resolve even moral questions.

Take homosexuality, for example. Iron age scriptures might argue that homosexuality is "wrong", but scientific discoveries about the frequency of the homosexual behavior in a variety of species tell us that it is completely natural in a rather fixed fraction of populations and that it has no apparent negative evolutionary impacts. This surely tells us that it is biologically based, not harmful and not innately "wrong". In fact, I think you actually accede to this point about the impact of science when you argue that our research into non-human cognition has altered our view of ethics.

I admit I am pleased to have read that you agree that "why is there something rather than nothing?" is a question best addressed by scientists. But, in this regard, as I have argued that "why" questions are really "how" questions, would you also agree that all "why" questions have no meaning, as they presume "purpose" that may not exist?

JB It would certainly be foolish to rule out in advance the possibility that what now appears to be a non-factual question might one day be answered by science. But it's also important to be properly sceptical about how far we anticipate science being able to go. If not, then we might be too quick to turn over important philosophical issues to scientists prematurely.

Your example of homosexuality is a case in point. I agree that the main reasons for thinking it is wrong are linked with outmoded ways of thought. But the way you put it, it is because science shows us that homosexual behavior "is completely natural", "has no apparent negative evolutionary impacts", is "biologically based" and "not harmful" that we can conclude it is "not innately 'wrong'". But this mixes up ethical and scientific forms of justification. Homosexuality is morally acceptable, but not for scientific reasons. Right and wrong are not simply matters of evolutionary impacts and what is natural. There have been claims, for example, that rape is both natural and has evolutionary advantages. But the people who made those claims were also at great pains to stress this did not make them right – efforts that critics sadly ignored. Similar claims have been made for infidelity. What science tells us about the naturalness of certain sexual behaviors informs ethical reflection, but does not determine its conclusions. We need to be clear on this. It's one thing to accept that one day these issues might be better addressed by scientists than philosophers, quite another to hand them over prematurely.

LK Once again, there are only subtle disagreements. We have an intellect and can, therefore, override various other biological tendencies in the name of social harmony. However, I think that science can either modify or determine our moral convictions. The fact that infidelity, for example, is a fact of biology must, for any thinking person, modify any "absolute" condemnation of it. Moreover, that many moral convictions vary from society to society means that they are learned and, therefore, the province of psychology. Others are more universal and are, therefore, hard-wired – a matter of neurobiology. A retreat to moral judgment too often assumes some sort of illusionary belief in free will which I think is naive.

I want to change the subject. I admit I am pleased that you agree that "why is there something rather than nothing" is a question best addressed by scientists. But I claim more generally that the only meaningful "why" questions are really "how" questions. Do you agree?

Let me give an example to put things in context. Astronomer Johannes Kepler claimed in 1595 to answer an important "why" question: why are there six planets? The answer, he believed, lay in the five Platonic solids whose faces can be composed of regular polygons – triangles, squares, etc – and which could be circumscribed by spheres whose size would increase as the number of faces increased. If these spheres then separated the orbits of the planets, he conjectured, perhaps their relative distances from the sun and their number could be understood as revealing, in a deep sense, the mind of God.

"Why" was then meaningful because its answer revealed a purpose to the universe. Now, we understand the question is meaningless. We not only know there are not six planets, but moreover that our solar system is not unique, nor necessarily typical. The important question then becomes: "How does our solar system have the number of planets distributed as it does?" The answer to this question might shed light on the likelihood of finding life elsewhere in the universe, for example. Not only has "why" become "how" but "why" no longer has any useful meaning, given that it presumes purpose for which there is no evidence.

JB I don't know whether it's a virtue or a vice, but in philosophy, there is nothing "only" about subtle disagreements! But given we've got as close as we're probably going to on ethics, let's turn to the difference between "how" and "why" questions.

Again, I agree with a lot here. I am unpersuaded, for example, by the argument that there is never any conflict between religion and science because the latter deals with "how" questions and the former "why" ones. The two cannot be so easily disentangled. If a Christian argues that God explains why there was a big bang, then that inevitably says something about God's role in how the universe came into being, too. But I would not go so far as to say that all "why" questions can only be properly understood as "how" ones. The clearest example here is of human action, for which adequate explanations can rarely do without "why" questions. We do things for reasons.

Some very hard-nosed philosophers and scientists describe this as a convenient fiction, an illusion. They claim the real explanation for human action lies at the level of "how", specifically, how brains receive information, process it and then produce action.

But if we want to know why someone made a sacrifice for a person close to them, a purely neurological answer would not be a complete one. The full truth would require saying that there was a "why" at work, too: love. Love is indeed at root the product of the firings of neurons and release of hormones. How the biochemical and psychological points of view fit together is clearly puzzling, and, as your aside on free will suggests, our naive assumptions about human freedom are almost certainly false. But we have no reason to think that one-day science will make it unnecessary for us to ask "why" questions about human action to which things such as love will be the answer. Or is that romantic tosh? Is there no reason why you're bothering to have this conversation, that you are doing it simply because your brain works the way it does?

LK Well, I am certainly enjoying the conversation, which is apparently "why" I am doing it. However, I know that my enjoyment derives from hard-wired processes that make it enjoyable for humans to tangle linguistically and philosophically. I guess I would have to turn your question around and ask why (if you will excuse the "why" question!) you think that things such as love will never be reducible to the firing of neurons and biochemical reactions? For that not to be the case, there would have to be something beyond the purely "physical" that governs our consciousness. I guess I see nothing that suggests this is the case. Certainly, we already understand many aspects of sacrifice in terms of evolutionary biology. Sacrifice is, in many cases, good for the survival of a group or kin. It makes evolutionary sense for some people, in this case, to act altruistically, if propagation of genes is driving action in a basic sense. It is not a large leap of the imagination to expect that we will one day be able to break down those social actions, studied on a macro scale, to biological reactions at a micro scale.

In a purely practical sense, this may be computationally too difficult to do in the near future, and maybe it will always be so, but everything I know about the universe makes me timid to use the word always. What isn't ruled out by the laws of physics is, in some sense, inevitable. So, right now, I cannot imagine that I could computationally determine the motion of all the particles in the room in which I am breathing air so that I have to take average quantities and do statistics in order to compute physical behavior. But, one day, who knows?

JB Who knows? Indeed. Which is why philosophy needs to accept it may one day be made redundant. But science also has to accept there may be limits to its reach.

I don't think there is more stuff in the universe than the stuff of physical science. But I am sceptical that human behavior could ever be explained by physics or biology alone. Although we are literally made of the same stuff as stars, that stuff has organised itself so complexly that things such as consciousness have emerged that cannot be fully understood only by examining the bedrock of bosons and fermions. At least, I think they can't. I'm happy for physicists to have a go. But, until they succeed, I think they should refrain from making any claims that the only real questions are scientific questions and the rest is noise. If that were true, wouldn't this conversation just be noise too?

LK We can end in essential agreement then. I suspect many people think many of my conversations are just noise, but, in any case, we won't really know the answer to whether science can yield a complete picture of reality, good at all levels, unless we try. You and I agree fundamentally that physical reality is all there is, but we merely have different levels of optimism about how effectively and how completely we can understand it via the methods of science. I continue to be surprised by the progress that is possible by continuing to ask questions of nature and let her answer through experiment. Stars are easier to understand than people, I expect, but that is what makes the enterprise so exciting. The mysteries are what make life worth living and I would be sad if the day comes when we can no longer find answerable questions that have yet to be answered, and puzzles that can be solved. What surprises me is how we have become victims of our own success, at least in certain areas. When it comes to the universe as a whole, we may be frighteningly close to the limits of empirical inquiry as a guide to understanding. After that, we will have to rely on good ideas alone, and that is always much harder and less reliable.

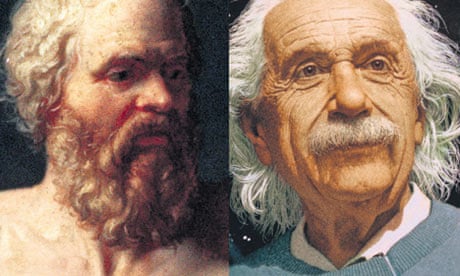

Julian Baggini is a British philosopher and Lawrence M. Krauss is a Canadian-American theoretical physicist.

No comments:

Post a Comment