By Kimon de Greef, The New York Times, July 6, 2018

|

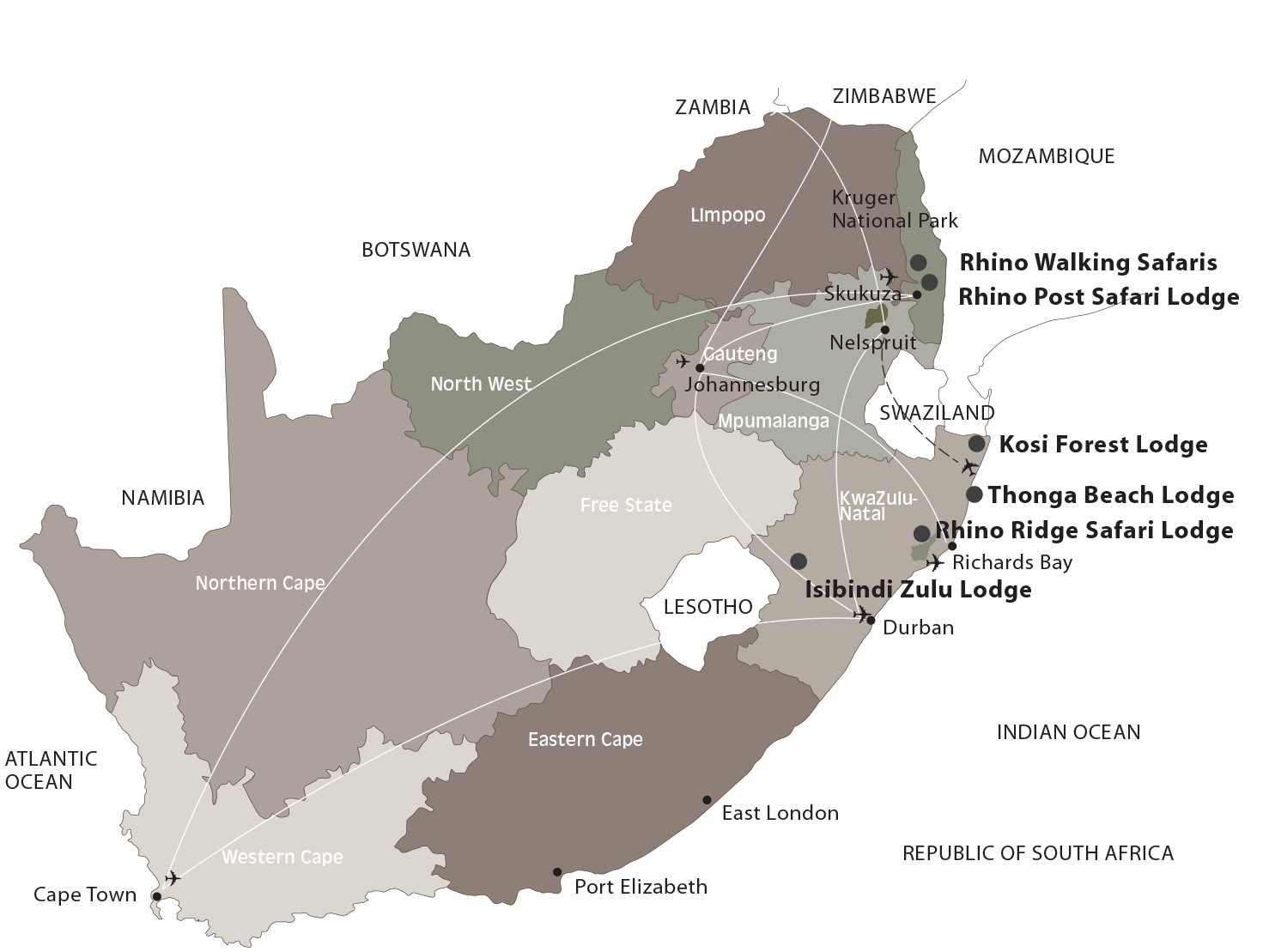

| Rhinoceros reserves in South Africa |

CAPE TOWN — In the cold hours before dawn this week on a South African game reserve, a dog began barking. It was a special breed of Belgian sheepdog, and its job was to listen for poachers.

The dog’s handler, trained to guard rhinoceroses, could hear a pride of lions in the distance. He decided it was a false alarm. But that Monday evening, rangers came across the remains of men suspected of being poachers.

“One of our guys found what he thought was a soccer ball,” Nick Fox, the owner of the private game reserve in Eastern Cape Province, said on Friday. “It turned out to be a skull.”

The next morning, rangers and police officers said that as many as three men suspected of being rhino poachers had been killed by lions in an area densely packed with thorn bushes.

“There was nothing we could do before that,” Mr. Fox said. “It was getting dark — too unsafe to be on foot.” He added, “Once lions have taken down a human, you cannot be on the ground with them.”

To get to the remains, the rangers had to shoot the lions with darts to knock them out.

The men killed had been carrying a high-caliber rifle and an ax for chopping off the horns of the animals they planned to hunt, Mr. Fox said. They also had food to last several days — “mostly bread,” Mr. Fox said — and wire cutters for getting through fences. His estimate of three victims was based on counting their clothes and shoes.

Rhino horn is worth about $9,000 per pound in Asia, driving a lucrative and illicit trade. It is a prized ingredient in Chinese traditional medicine and is considered a status symbol.

South Africa is home to about 20,000 wild rhinos, more than 80 percent of the world’s population. About one-third of the animals are owned by private breeders. Since 2008, more than 7,000 rhinos have been hunted illegally, with 1,028 killed in 2017, according to the South African Department of Environmental Affairs.

Capt. Mali Govender of the Eastern Cape police service confirmed the deaths and said that the remains had been sent for forensic testing. But she said it “was not possible to speculate” how many victims had died.

Of the rifle recovered from the scene, which had been fitted with a silencer, Captain Govender said, “You don’t take a pellet gun to a game farm.”

People suspected of being poachers have been killed by lions in South Africa before. In February, a man’s mauled body was found in a reserve near Kruger National Park.

Mr. Fox, who established his game reserve, called Sibuya, in 2003, said there was “virtually no poaching at all” in the Eastern Cape until 2010, when suddenly it became a “serious problem.”

A single rhinoceros was poached in the Eastern Cape in 2007, according to the province’s environment department. In 2016, poachers killed 19.

“There are more poachers now, and they are very well equipped,” Mr. Fox said. To protect the rhinos on his property, he said, he had set up an antipoaching unit with guards, dogs and patrol vehicles.

“You literally need to have your own private army now,” he said, estimating the cost to him at more than $73,000 a year.

He would not confirm how many rhinoceroses were on his farm, heeding a nationwide moratorium on publicizing the numbers. In March 2016, he lost three rhinos to poaching, he said.

“You literally need to have your own private army now,” he said, estimating the cost to him at more than $73,000 a year.

He would not confirm how many rhinoceroses were on his farm, heeding a nationwide moratorium on publicizing the numbers. In March 2016, he lost three rhinos to poaching, he said.

“It’s devastating when that happens,” he said. “This time, there’s a huge sense of relief.”

According to Annette Hübschle, a researcher at the University of Cape Town’s Center of Criminology, rhino poaching has been expanding from Kruger National Park, in northeastern South Africa, because of militarized antipoaching crackdowns.

“You now have traveling poaching gangs,” Dr. Hübschle said, adding, “Rhino horn has huge value, so even low-level poachers can make a lot of money.”

“Selling a single horn can exceed the yearly income of most rural people,” Dr. Hübschle said.

The Eastern Cape is South Africa’s poorest province, with a gross domestic product of less than $3,700 per capita. The unemployment rate here, including people who have given up looking for work, exceeds 45 percent, significantly higher than the national average.

“Behind poaching there’s a bigger story of structural inequality,” Dr. Hübschle said. “People were chased off their land during colonialism and apartheid, losing their customary hunting rights and tenure. Today, many local communities experience some trickle-down from poaching, while attitudes are generally negative towards private game owners and protected areas.”

Responding to the death of the men, some residents saw a moral lesson. Annamiticus, a wildlife crime advocacy group, wrote on its website that “a gang of rhino killers apparently received a dose of their own medicine.” On social media, many users saw it as “karma.”

“Whenever the death of a poacher is reported, there’s this horrendous outpouring,” Dr. Hübschle said. “People seem absolutely delighted at the death of local people.”

Julian Rademeyer, a project leader of Traffic, a nonprofit group that monitors illegal wildlife trades, and the author of “Killing for Profit,” about rhino poaching in South Africa, said: “It is doubtful that these deaths will deter other poachers. The middlemen will simply up the price they are prepared to pay, and more young men will line up to kill or die.”

No comments:

Post a Comment