By Stephanie Buch, Timeline, August 4, 2016

|

The Garden of Earthly Delight, Hieronymus Bosch circa 1500. (Wikimedia Commons)

Even if you haven’t so much as clipped a basil plant, you are the descendant of someone who tilled a field. And that person most likely participated in one of humankind’s earliest monogamous relationships. That’s because monogamy likely wasn’t commonplace until the invention of private property.

Before about 8,000 B.C.E. gathering food and resources was constant, and there was rarely extra. So, for the survival of all and the need to procreate, our prehistoric ancestors lived in nomadic clans — sharing everything from meals to childcare to sexual partners. These tribes had little hierarchical structure. Everyone played a crucial role in community survival. Everyone contributed to a shared group identity.

In such social structures, omnigamy thrived, posited 19th Century American anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan. Omnigamy was group partnerships among all genders in a large group, a step beyond polygamy, depending on your definition. Under such egalitarian circumstances, casual sex with multiple partners was the norm, according to the authors of Sex at Dawn. There was no shame or taboo about it. It follows, that everyone cared for everyone else’s children, too.

|

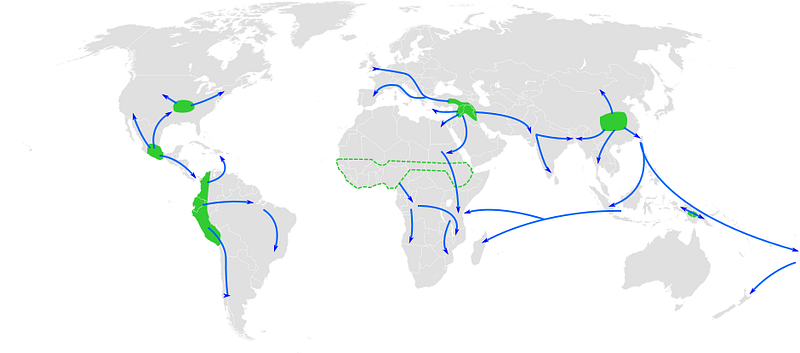

| Map of the world showing approximate centers of origin of agriculture and its spread in prehistory (Wikimedia Commons) |

However, between 12,000 and 4,000 B.C.E., in a period known as the Neolithic Revolution, humans learned to cultivate most of agriculture’s fundamental crops in the world’s major regions. Rice and soybean farming originated in China, pigs were domesticated in what is now modern Turkey, maize crops came from North America, etc.

Land settlement generally lead to a more sedentary lifestyle around urban centers — no more moving to follow food supply. Just grow some more. In many places, such as Western Europe, food surplus led to profit potential; private property became precious. And land wasn’t the only thing to own.

Women’s roles as community leaders shrunk. They were isolated in a new patriarchy, their bodies and babies mere chips in the agricultural economy.

From there, fierce competition for wealth divided communities into smaller units and eventually into nuclear families. Monogamy ruled, and still does.

But some argue our earlier ancestors had it right. Polyamory isn’t just an experimental phase for Tinder users; it’s coming out of the shadows as a legitimate alternative to coupledom.

Added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2006, polyamory is the practice of forging intimate relationships with multiple people at a given time. Unlike hookup culture participants, poly people seek genuine emotional connection with two or more partners. Polyamory may exist in closed relationships of triads or quads (three people or two couples, respectively), or more. Group marriages or “tribes” of many people consider themselves one cohesive relationship unit, not unlike those nomadic tribes.

Though research is still minimal, experts suggest roughly 4 to 5 percent of the U.S. population seeks romantic relationships outside monogamy, with their partner’s permission.

Not surprisingly, today’s poly practitioners differ from our ancestors. For one, we have different laws and governing bodies, social taboos, economics, and gender roles. Our ideas of consent are different. Also known as “consensual non-monogamy,” polyamory today emphasizes constant, open communication and respect among participants, perhaps a set of rules (“no sleeping with someone else in our shared bed at home,” for instance).

It can get complicated, of course, especially because we can’t shatter the ingrained norms of monogamy overnight. “A heterosexual, normative relationship is much easier to be in because the rules are there — that’s considered cheating, that’s not,” a woman named Maria tells Vice. “[In polyamory] you’re constantly talking about what the rules are.”

Not to mention that coming out as polyamorous to one’s family, even if they were Baby Boomers of the sexual revolution, is likely fraught with anxiety. The majority of estate and insurance laws also refuse to acknowledge triad relationships. Having children may complicate things even further on that front.

Poly people have many different reasons to choose this lifestyle, but a big one is “yearning for community,” the innate need to connect rather than isolate. We’re not here to debate whether polyamory is the “natural” human state, but sharing love widely worked for a long time. The poly community calls it “compersion,” the feeling of pleasure one gets when their partner is fulfilled by another person’s love — the opposite of jealousy.

If this idea sounds distant and utopian, fine. But neither was monogamy a natural “fix” for human sexuality, if such a thing exists. It was merely one consequence in a world increasingly driven by commerce, a means of property ownership in the new agricultural economy.

Who knows, maybe technology will be to monogamy what agriculture was to polyamory: one phases the other out. Maybe Tinder is the new soybean.

No comments:

Post a Comment