Call it the Saudi calculus.

Oil prices were already plummeting 14 months ago when, at Saudi Arabia’s insistence, OPEC put the global petroleum industry on notice: The member countries would not try to prop up prices by cutting production.

“We don’t want to panic,” Abdalla el-Badri, secretary general of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, told reporters at the group’s November 2014 meeting in Vienna. “We want to see how the market behaves.”

Since then, the market has behaved in a way few could have predicted — including Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest oil exporter. The price of oil has collapsed under the weight of a growing international glut, made worse by slower growth in the global economy.

And yet the Saudis keep pumping oil at virtually full capacity. And they have persuaded their Persian Gulf OPEC allies — Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar — to do the same, despite mounting pressure from other big OPEC members to curtail production.

It is a risky strategy — one that is already straining Saudi finances and threatening the kingdom’s ability to continue providing generous social programs, like subsidized housing and cheap energy, that the royal family has long used to buy domestic tranquillity.

Oil provides more than 70 percent of Saudi government revenue. And though the Saudis still have about $630 billion in financial reserves, they are spending them at a rate of $5 billion to $6 billion a month, according to Rachel Ziemba, an analyst at Roubini Global Economics in New York.

But so far, Saudi Arabia is essentially betting that it can win an oil-price war of attrition — not only against its OPEC rivals like Iran, Iraq and Venezuela, but also against non-OPEC rivals like Russia and the many shale-oil producers in the United States that have contributed to the global glut.

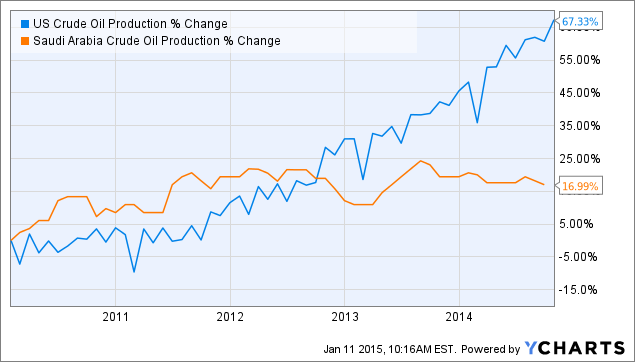

The Saudis argue that throttling back oil production for a short-term pop in the price would be throwing a lifeline to the shale producers in the United States, some of which have already shown signs of wilting in the current environment.

Already, oil producers have dropped their rig count in the United States as bankruptcies spread in the oil patch. But daily production has remained resilient as the wells that remain become more efficient and as major oil projects in the Gulf of Mexico, conceived in an era of $100-a-barrel oil, come online.

On top of this, Iran can increase exports now that Western sanctions have been partly lifted, potentially raising its daily production well above the current level of 2.9 million barrels a day.

With the world awash in oil, the Saudis fear that cutting back might achieve nothing but erosion of their own share of the market — which is one of every nine barrels produced worldwide.

All of this adds up to oil prices that are not likely to rise significantly higher any time soon, unless the Saudi kingdom suddenly changes course.

“If prices continue to be low, we will be able to withstand it for a long, long time,” Khalid al-Falih, the chairman of Saudi Aramco, the kingdom’s national oil company, said last week at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

On Wednesday, Brent crude, an international benchmark, was trading around $31.80 a barrel. That is above the 12-year low of about $27 that oil hit last week. But it is still down more than 70 percent from the level of about $114 in mid-2014, before the price began collapsing.

As daring, or even self-defeating, as the Saudi approach might seem, it is a policy born of pragmatism. Whatever Saudi Arabia does with oil production, its two big OPEC neighbors — Iraq and Iran, the Saudis’ biggest regional rival — might have their own economic and geopolitical reasons to keep pumping or even raising output. And Russia, a big non-OPEC producer, is embroiled in a financial crisis from plunging oil prices and Western sanctions that might give it little choice but to maintain production and take whatever revenue it can.

The Saudis also need a high level of production to support their export network and their domestic refineries and petrochemical industry.

“In order to maintain an efficient economy in terms of investment you can’t be pushing your production up and down a half a million barrels every time the market requires it to prop up prices,” said Sadad al-Husseini, a former executive vice president of Saudi Aramco, who now runs Husseini Energy, a consulting firm with offices in Bahrain and

Still, the Saudis know that they are in for tough times and that their dependence on oil has left them vulnerable.

At a time of great political ferment in the Middle East, the plunging oil prices have gutted the export revenue that drove economic growth in Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf countries in recent years. The Saudi kingdom is staring at a growing budget deficit and facing the specter of an economic recession.

The Saudi government has already had to curtail some of its generous social subsidies, recently increasing consumer gasoline prices. And in hopes of finding a new way to monetize its oil assets and begin diversifying its oil-dependent economy, the kingdom has even floated the idea of a public stock offering for Saudi Aramco.

“As far as I am concerned, the strategy is not working,” Nordine Ait-Laoussine, a former energy minister of Algeria, an OPEC member, said of the Saudi commitment to high oil production.

Mr. el-Badri, the OPEC secretary general, who is Libyan, has evidently watched the market’s behavior for long enough. This week, he called for a collective effort to reduce the global oil glut.

“It is crucial that all major producers sit down to come up with a solution to this,” he said on Monday in a speech at Chatham House, a research institution in London.

Venezuela has been pressing for an emergency meeting of cartel members.

But the Saudis are standing firm. “Our investments in capacity of oil and gas have not slowed down,” Mr. al-Falih, the Saudi Aramco chairman, said on Monday.

The Saudis still speak darkly of the 1980s when as OPEC’s “swing producer” they curtailed production to prop up prices but ended up badly burned when other producers did not go along. Seeing its oil revenue and market share shrink, Saudi Arabia fought back with its own price war.

With OPEC having about one-third of the world market, for the Saudis to agree to a cut would mean persuading producers outside the organization, potentially including Russia, to make comparable trims. Analysts say that such a deal would be difficult to arrange, though it could eventually become necessary.

“I can imagine a set of circumstances that could develop this year, including a fall in U.S. output, where the economic pain would force countries to act to stabilize the price,” said Jason Bordoff, a former energy adviser in the Obama administration who is now the director of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

But Mr. Bordoff and other analysts say that from a Saudi perspective this is not an opportune time to consider cuts. Not only is Iran’s re-entry on the global market expected to increase supplies, but Iraq has also been increasing production rapidly.

Still, though the Saudis are burning through their financial reserves, there is no danger of depleting them soon.

Because of that, Bhushan Bahree, an OPEC analyst at the energy consulting firm IHS Energy in Washington, expects the Saudis to stay the course.

If Saudi Arabia cuts production on its own, Mr. Bahree said, “What is next? Iran produces more; Iraq produces more. So what have they done? Pushed the price up temporarily but lost market share, which they may have difficulty recovering.”

No comments:

Post a Comment