HOUSTON — The world is awash in crude oil, with enough extra produced last year to fuel all of Britain or Thailand. And the price of oil will not stop falling until the glut shrinks.

The oil glut — the unsold crude that is piling up around the world — is a quandary and a source of investor anxiety that once again rattled global markets on Friday.

As prices have dropped, the amount of excess production has been cut in half over the last six months. About one million barrels of extra oil is now being dumped on the markets each day.

But that means the glut is still continuing to grow, and it could take years to work through the crude that is being warehoused, poured into petroleum depots or loaded onto supertankers for storage at sea.

The shakeout will be painful, taking an even bigger toll on companies, countries and investors.

Global stocks sank sharply on Friday, as the price of oil slipped below $30 a barrel. The glut was at the heart of the tumult, as investors worried that the demand from China would drop and supplies from Iran would grow.

“The glut is the 800-pound gorilla in the room,” said Steve McCoy, vice president for drilling contracts at Latshaw Drilling, an Oklahoma service company that prospered in recent years from the American shale boom. “The world simply produced too much, and now we have to use it up or many oil-producing countries and some oil companies may drown.”

Just a couple of years ago, producers and petro-states were making vast fortunes drilling and pumping relentlessly to fuel expanding middle classes in Asia, Latin America and Africa. But suddenly they are producing more than anyone needs at a time when China and other rapidly growing economies, once hungry for energy, are pulling back.

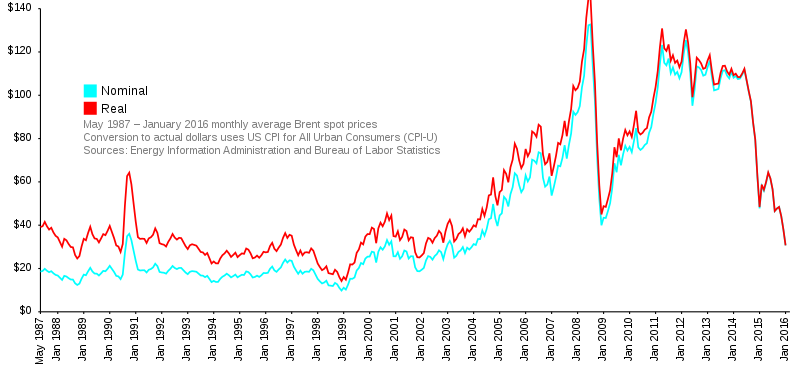

The extra oil has sent the price of crude into a tailspin, down more than 70 percent over the last 18 months.

That, in turn, has helped depress stock markets around the world, as investors worry about global growth. The Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index is off around 8 percent in just the first two weeks of the year; European shares are down even more. Chinese stocks have dropped 20 percent from their December peak, putting the market in bear territory.

“What was once viewed as a gift is now viewed similarly to the gift of the monkey’s paw,” said Tom Kloza, global head of energy analysis for Oil Price Information Service. “Global financial damages trump the benefits of cheap oil at anything under $30 a barrel.”

It could get worse.

The nuclear deal with Iran should allow the country to start exporting far more oil, once sanctions are lifted, potentially in a matter of days. Iran could add as much as 500,000 barrels a day to the global markets.

Tentative progress in negotiations between warring factions in Libya, battling for control of oil and export terminals, could unleash another flood. And Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq continue to maintain a pumping frenzy to grab Asian markets.

The United States is slowly cutting production. Major oil companies have dropped their rig count, and dozens of small businesses have gone bankrupt. But the industry cannot simply flip the switch on big projects, like deepwater production projects in the Gulf of Mexico, that require companies to keep pumping to cover their costs. Smaller companies have to keep producing from shale fields, even at a loss, to keep paying their lenders.

“Sheikhs and shale caused this,” said Scott Tinker, director of the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin. “They are both producing more oil. That is the fundamental driver.”

A million to two million barrels a day of excess production may not seem like much in a world market that requires 94 million barrels daily. But the amount of daily oversupply in recent months is the largest since oil prices collapsed in the late 1990s.

Back then, the price dropped below $10 a barrel, on an inflation-adjusted basis. Oil from new fields flooded the market just as the Asian financial crisis was roiling emerging markets.

Most of the glut today can be explained by a near doubling of American domestic oil production since 2008. The shale boom added roughly three million barrels a day to the global market.

In the past, when markets got out of kilter, Saudi Arabia and its partners in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries slashed production to support prices. But this time, the Saudis and other big producers increased output to try to preserve market share and undercut higher-cost competitors like those drilling in the shale fields of Texas and North Dakota.

Even as prices slipped through 2015, global production climbed. The Energy Department projects that overall inventories will rise by an additional 700,000 barrels a day in 2016.

The balance of oil supply and demand can swing abruptly, along with price, as they did in the early 2000s.

At the time, the Chinese and other emerging-market economies went into overdrive just as production in the United States and Mexico was declining and big producers like Venezuela and Nigeria were facing political turbulence. By mid-2008, the price of oil had risen to nearly $150 a barrel.

That is the possibility that many analysts are now contemplating, even if not at a price that high. An unexpected drop in supply or rise in demand could create a floor for prices, ease the glut and eventually lead to a slow recovery.

On the supply side, if tensions erupting between Saudi Arabia and Iran lead to armed conflict or an insurrection, the excess production could quickly disappear.

The boom in Iraqi oil production faces multiple threats, including Islamic State terrorism. The government is falling behind in its payments to international oil companies, water is running low for pumping to revive aging oil fields, and northern Kurdish fields are short on pipelines.

Low oil prices have already constrained exploration and production investment around the world.

American oil producers are in retreat; companies have decommissioned more than 60 percent of their rigs in the last year or so. Since peaking at 9.7 million barrels a day early last year, domestic oil production has fallen by more than half a million barrels. Rosneft, Lukoil and Western companies are also dropping big projects in Russia.

Some analysts also say that the concerns about slowing demand in emerging markets, a byproduct of the economic weakness, are overblown. China and India, for example, are working hard to build up enormous strategic reserves, which adds to the demand.

RBC Capital Markets, a division of Royal Bank of Canada, estimates that China’s needs will continue to grow as it places an additional 65 million to 70 million barrels in its reserves this year. India began amassing a strategic reserve only last year, and it has a goal of storing roughly 330 million barrels over the next several years.

“Increased demand can certainly help,” said Michael Tran, an RBC commodity strategist. “But the growing supply glut is what ultimately got us below $30-a-barrel oil, and significant supply cuts are what will ultimately have to dig us out.”

No comments:

Post a Comment