By Ian Johnson, The New York Review of Books, January 19, 2017

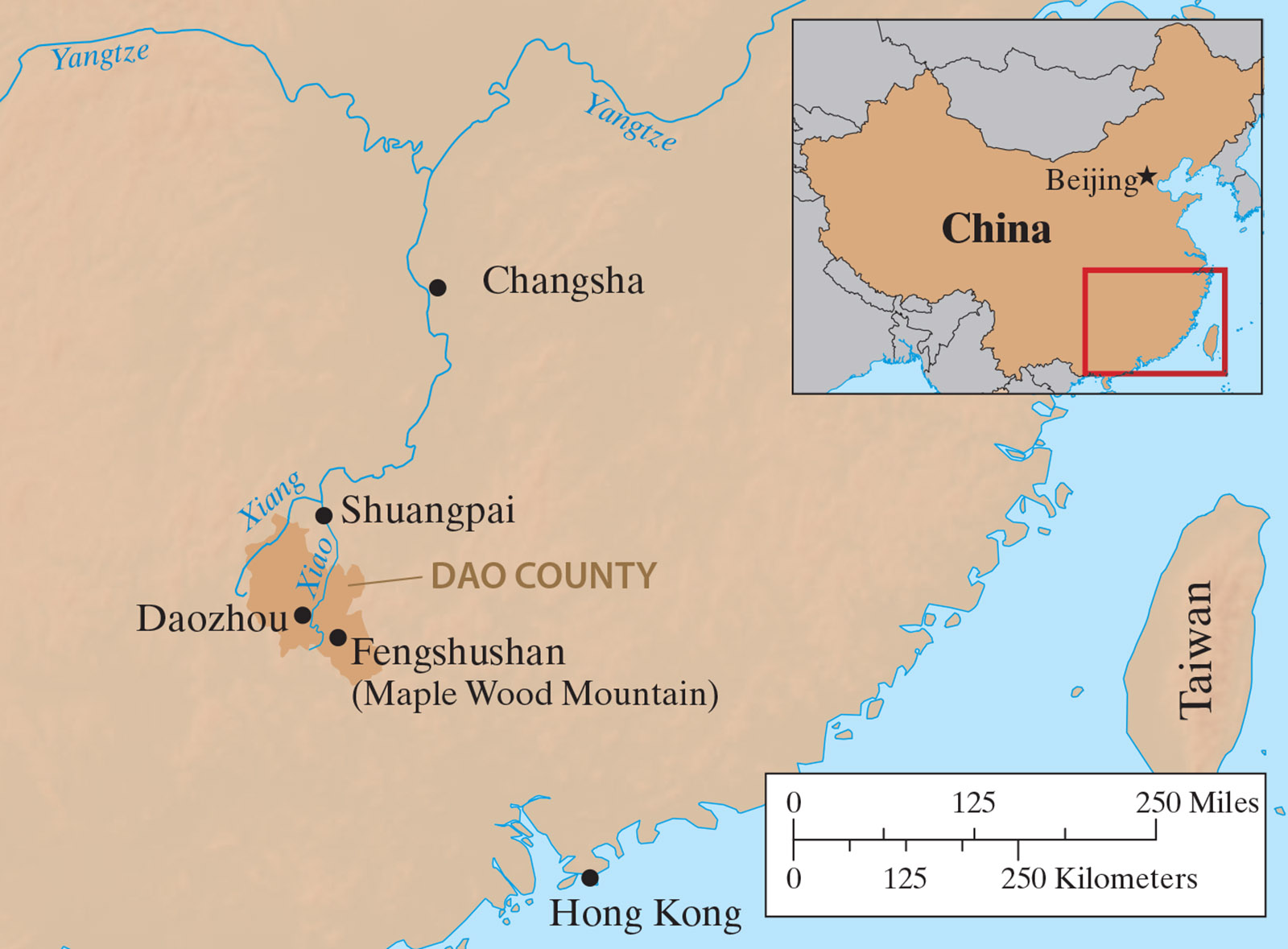

The Xiao River rushes deep and clear out of the mountains of southern China into a narrow plain of paddies and villages. At first little more than an angry stream, it begins to meander and grow as the basin’s sixty-three other creeks and brooks flow into it. By the time it reenters the mountains fifty miles to the north, it is big and powerful enough to carry barges and ferries.

Fifty years ago, these currents transported another cargo: bloated corpses. For several weeks in August and September 1967, more than nine thousand people were murdered in this region. The epicenter of the killings was Dao County (Daoxian), which the Xiao River bisects on its way north. About half the victims were killed in this district of four hundred thousand people, some clubbed to death and thrown into limestone pits, others tossed into cellars full of sweet potatoes where they suffocated. Many were tied together in bundles around a charge of quarry explosives. These victims were called “homemade airplanes” because their body parts flew over the fields. But most victims were simply bludgeoned to death with agricultural tools—hoes, carrying poles, and rakes—and then tossed into the waterways that flow into the Xiao.

In the county seat of Daozhou, observers on the shoreline counted one hundred corpses flowing past per hour. Children danced along the banks competing to find the most bodies. Some were bound together with wire strung through their collarbones, their swollen carcasses swirling in daisy chains downstream, their eyes and lips already eaten away by fish. Eventually the cadavers’ progress was halted by the Shuangpai dam where they clogged the hydropower generators. It took half a year to clear the turbines and two years before locals would eat fish again.

For decades, these murders have been a little-known event in China. When mentioned at all, they tended to be explained away as individual actions that spun out of control during the heat of the Cultural Revolution—the decade-long campaign launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 to destroy enemies and achieve a utopia. Dao County was portrayed as remote, backward, and poor. The presence of the non-Chinese Yao minority there was also sometimes mentioned as a racist way of explaining what happened: those minorities, some Han Chinese say, are only half civilized anyway, and who knows what they might do when the authorities aren’t looking?

All of these explanations are wrong. Dao County is a center of Chinese civilization, the birthplace of great philosophers and calligraphers. The killers were almost all Chinese who murdered other Chinese. And the killings were not random: instead they were acts of genocide aimed at eliminating a class of people declared to be subhuman. That class consisted of make-believe landlords, nonexistent spies, and invented insurrectionists. Far from being the work of frenzied peasants, the killings were organized by committees of Communist Party cadres in the region’s towns, who ordered the murders to be carried out in remote areas. To make sure revenge would be difficult, officials ordered the slaughter of entire families, including infants.

That we know the truth about Dao County is due to one person: a garrulous, stubborn, and emotional editor who stumbled over the story thirty years ago and decided that it was his fate to tell it. His name is Tan Hecheng and in December I set off for southern China to meet him.

Maple Wood Mountain, or Fengshushan, is a tribute to the development carried out by the dictatorship that runs China. When Tan first visited this village thirty years ago, it had no roads. A car drove him to a nearby town but he had to hike the remaining three miles up the mountain. The area was so poor that even a simple wristwatch was an unimaginable luxury, let alone electricity or running water.

Now, the path has been widened and surfaced with concrete slabs. As we picked our way up the mountain in our SUV, we passed a team of laborers expanding it into a paved road with guardrails. Electricity, water, and cell phone coverage were now givens. Many families sent their children to boarding schools in the nearby township, but for the very poor the state had provided a single-room schoolhouse. When we arrived, eleven children aged six to ten sat under Communist Party propaganda posters, learning math.

Behind the school was another monument to the all-powerful state: a stone stele with a couplet that read:

Father and Children, Rest in Peace

Those in this World, a Life of Peace

Several other lines explained the meaning. They listed the names of the dead father and three children, and the person who erected the stele—the person still in this world who needed peace—their wife and mother, Zhou Qun.

As we stood there examining the tombstone, a change came over Tan. During the previous two days we had traveled tirelessly through the county as he tried to show us every major killing field and talk to as many survivors as possible. A boisterous sixty-seven-year-old with soft features and an unruly cowlick, he had an irrepressible gallows humor. Sometimes when we drove by a village, he would start to recount the details of who was bludgeoned or shot, but then cut himself short by shouting out: “Fuck, in this place they killed a lot of people!”

But on this ridge, in front of this tombstone, he suddenly slowed down as the memories of the past overcame him. He had been thirty-seven when he came here in 1986, a man who had lost his youth to Mao and his Cultural Revolution, and who finally had the assignment of a lifetime. He had been sent by a magazine to write about Dao County. A thirteen-hundred-person secret government commission had just investigated the killings and he had full access to its findings. But his article had been declared too pessimistic—the editors had wanted an upbeat piece on how the Communist Party had dealt with the past swiftly and fairly. In fact, he had realized that the truth had been buried. Justice had not been done. Only a tiny fraction of the killers had served jail time. And he knew then that his article would probably be killed.

Still he wrote it and gave it the name Xue zhi Shenhua, or Blood Myths. That title irritated me—these weren’t myths but facts that he had carefully reconstructed based on the commission’s thousands of pages of findings and documents, as well as his own months in the region. The English title, The Killing Wind, made more sense to me. People here still spoke of a “killing wind” that had blown through during the Cultural Revolution. I had asked him about the Chinese title a day or two earlier, but he only began to explain it here, in front of the tombstone.

“The title is not a way to soften the truth. The title doesn’t mean a myth in the sense of something half-true or rumored. What I meant was that some stories hit me with such force that they became mythic.” He pointed to the stone, crudely hewn from rock, the characters so cheaply and shallowly carved that they were already becoming illegible just four years after the monument was erected. “I cried only three times in the years I spent researching the massacre. One time was when I realized what had happened to Zhou Qun.”

On August 26, 1967, Mrs. Zhou and her three children were dragged out of bed by leaders of the village of Tuditang. She had been working there for several years as a primary school teacher but had always lived under a cloud. Her father had been a traffic policeman during the time the Nationalist government had ruled China, which was enough to make her a “counterrevolutionary offspring.” That meant her family had been categorized as a “black element”—along with landlords, wealthy farmers, rightists (anyone who had voiced complaints in the late 1950s), and capitalists (usually small shopkeepers), as well as the catch-all “bad elements” (former prostitutes, opium smokers, homosexuals, and others seen as guilty of deviant behavior).

For the previous eighteen years of Communist rule, black elements like Mrs. Zhou and her family had lived a marginal existence. The state had stripped them of their property. It had assigned them bad jobs with low pay or rocky plots of land to farm. And it had inundated China with a barrage of propaganda intended to convince many that black elements were dangerous, violent criminals who were barely human.

In the Cultural Revolution, Mao whipped up the propaganda another notch, declaring that enemies were readying a counterrevolution. In Dao County, stories began to fly that the black elements had seized weapons. The county government decided to strike preemptively and kill them. When village-level officials objected—many were related to the victims—more powerful leaders sent out “battle-hardened” squads of killers (often former criminals and hoodlums) to put pressure on locals to execute the undesirables. After the first deaths, locals were freed from moral constraints and usually acted spontaneously, even against family members.

This was not exceptional. Most accounts of the Cultural Revolution have focused on the Red Guards and urban violence. But a growing number of studies show that genocidal killings were widespread. Previously, we knew of cases of cannibalism in Guangxi province. But recent research, as well as in-depth case studies like Tan’s, show that the killings were widespread and systematic instead of being isolated, sensational events. One survey of local gazetteers shows that between 400,000 and 1.5 million people perished in similar incidents, meaning there were at least another one hundred Dao County massacres around this time.

Mrs. Zhou was tied up and frog-marched to a threshing yard next to the storehouse. Thirteen others were there too, including her husband, who had been seized a day earlier. The group was ordered to set off on a march. At the last moment, one of the leaders remembered that Mrs. Zhou and her husband had three children at home. They were rounded up and joined the rest on a five-mile midnight trek through the mountains.

Exhausted, the group ended up at Maple Wood Mountain at the very spot where we now stood. A self-proclaimed “Supreme People’s Court of the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants” was formed out of the mob and immediately issued a death sentence to the entire group. The adults were clubbed in the head with a hoe and kicked into a limestone pit. Mrs. Zhou’s children wailed, running from adult to adult, promising to be good. Instead, the adults tossed them into the pit too.

Some fell down twenty feet to a ledge. Mrs. Zhou and one of her children landed alive on a pile of corpses on a higher ledge. When the gang heard their cries and sobs they tossed big rocks at the ledge until it collapsed, sending them down onto the others. Miraculously, all the family members survived. But as the days passed each of them died, until Mrs. Zhou was the last person in the pit with thirty-one corpses around her.

After a week, when an order from the Party had gone out to cease the killings, a few villagers from her hometown—which was not the village where she had been living—sneaked to the cave at night and rescued Mrs. Zhou. The village leadership from the town where she lived then recaptured her and debated killing her. Instead they tossed her in a pigsty and ordered the wardens not to feed her. But some courageous villagers tossed sweet potatoes into her cell at night and she survived another two weeks until a posse of villagers from her hometown freed her.

As Tan told us this story I thought back to the only other memorial in all of Dao County. It was erected by the son of a Chinese medical practitioner who was clubbed to death (his success as a doctor had made him prosperous and that made him a black element). The stele was similar to Mrs. Zhou’s. It just mentioned the facts and alluded to some sort of pain, without daring to be specific. The doctor’s stele stood alone in an empty field, surrounded by knee-high wild grass. It looked unremarkable until we approached it. There we saw something left behind by a mourner at a recent festival for the dead: two sabers, made for ritual use out of wood and silver foil, lying at the base of the monument, glinting in the sun.

On the fourth day of our stay, we drove up the Xiao River toward the Shuangpai dam. We had seen Mrs. Zhou earlier that morning. Now elderly but still very alert, she was unable to forget what had happened. She had remarried and had a daughter but the younger woman was unwilling to talk about the past, or even allow her mother to bring it up. This was not unusual for the victims’ offspring. Even though it was their parents who had suffered, the awful history seemed to cheapen or make hollow today’s world with its promise of prosperity and normalcy. The old victims and the dead were reminders of the past, and resented for it.

Along the way up toward the dam, Tan described what happened after his article was not published. He remained an editor at a state-run literary magazine but was kept on the margins. He was never promoted or allowed to attend conferences or become involved in competitions. But he kept at the subject of the killings, returning to Dao County and working on a definitive history. Eventually, he published his book in 2011 in Hong Kong and now we have the English version, abridged but not in a way that detracts from the overall story. It is masterfully translated by the team of Stacy Mosher and Guo Jian—the same who abridged and translated Yang Jisheng’s classic account of the Great Leap famine, Tombstone.

“You know, I can kiss ass as well as anyone,” Tan said as we made our way through the mountains. “I’m really good at it. In fact, I’m an excellent ass-kisser! I can tell people what they want to hear, and I can write an article in the way you want it. But I have a minimum moral standard: I can’t turn black into white. Somehow I just can’t do that.

“So when they said they wouldn’t publish it, I thought, ‘Okay, that’s your problem,’ but my life had changed and so I thought, ‘This is it. One way or another I will publish this.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment