By Alessandro Giardiello, In Defense of Marxism, January 17, 2020

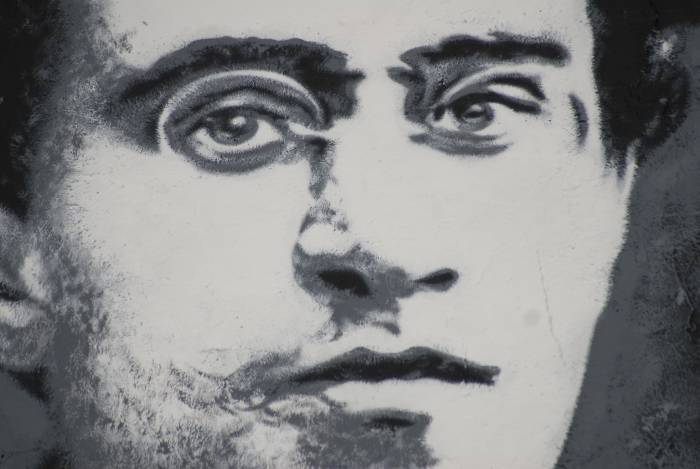

Antonio Gramsci died in 1937, after spending nearly ten years in prison under Mussolini’s fascist regime. All these years later, his ideas and legacy are still being debated and reinterpreted. Who was Gramsci? All manner of weird and wonderful answers have been given to this question, with plenty of distortions, if not outright historical falsifications, from petit-bourgeois academics and intellectuals, to revisionists in the labour movement.

"During the lifetime of great revolutionaries, the oppressing classes constantly hounded them, received their theories with the most savage malice, the most furious hatred and the most unscrupulous campaigns of lies and slander. After their death, attempts are made to convert them into harmless icons, to canonize them, so to say, and to hallow their names to a certain extent for the 'consolation' of the oppressed classes and with the object of duping the latter, while at the same time robbing the revolutionary theory of its substance, blunting its revolutionary edge and vulgarizing it."

(V.I. Lenin, The State & Revolution)

Attempts have been made to present Gramsci as a founding father of the Italian nation, allowing even right-wing bourgeois politicians like Berlusconi to claim his legacy. This is truly the last straw: after being painted as a precursor of popular frontism, of the “historic compromise”, of Eurocommunism; now he is to be added to the collection of “fathers of the Republic”, a neutral figure to be respected by all, regardless of where they lie on the political spectrum.

It is our duty, and the duty of every communist, to stand firmly against all attempts to distort the ideas of Gramsci, whether they come from a reformist or social chauvinist angle.

The New Order and the Livorno split

Firstly, it must be said that Gramsci, and the group in Turin organised around the newspaper The New Order (L’Ordine Nuovo), achieved the tremendous task of applying the general lessons of the October Revolution to the specific Italian context, and represented the most advanced layer of the Italian workers’ movement.

The “ordinovists” not only defended and organised the workers in the factory occupations in 1920 but became the theoretical leaders who clarified the role of workers’ control of industry. Gramsci believed that factory committees should be organs of working class power in the sphere of production, as well as the nuclei of workers’ democracy in the new socialist society.

During the Italian revolution of 1919-20, which would go down in history as the “red biennium”, Gramsci used the pages of The New Order to urge the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) to arm the industrial proletariat and the peasants with a revolutionary programme centred around the slogan “all power to the factory committees!”.

Without doubt these ideas were the result of the concrete experience of the workers in Turin, but we cannot ignore the influence of the Bolsheviks and the role of the Soviets in the October Revolution on Gramsci’s writings. It is not a coincidence that Gramsci wrote in The New Order: “the Soviet has proven itself to be immortal as the form of organised society that can adapt to various permanent and vital needs, both economic and political, of the vast majority of the Russian masses.”

Gramsci had two aims in the years 1919-1920, which, following Lenin, he considered fundamental to the revolutionary process. Firstly, the formation of organs of class struggle and workers’ democracy that could organise the broadest layers of the workers. Secondly, the development of a revolutionary leadership that would break with all reformist and centrist tendencies in the PSI and in the wider workers’ movement. The reformists like Turati and the centrists like Serrati and Lazzari represented an obstacle to the revolution: the former refuted its necessity; the latter defended it but, not contributing to its organising, were de facto boycotting it.

Gramsci’s factional struggle in the PSI began in November 1920 when the communist faction was formed at Imola, under Amedeo Bordiga’s initiative. In January 1921 at Livorno this revolutionary faction split and the Italian Communist Party (PCI) was born. At the Livorno Congress, 58,873 socialist militants and the entire Socialist Youth went with the communists, 98,023 supported the centrist faction and 14,695 remained with Turati’s reformists.

The Comintern supported the split, and its Executive Committee, taking into consideration Serrati’s refusal to expel Turati’s reformists from the party, declared the PCI the only Italian section of the Comintern, supporting the self-exclusion of the PSI.

At the Third Congress of the Comintern (June 1921), the PSI sent a delegation consisting of Lazzari, Maffi and Riboldi to apply for membership in the Comintern. The request was denied, but the leadership of the Comintern suggested to the PCI to apply the tactic of the united front with the PSI, with the aim of attracting those socialists who viewed the USSR enthusiastically and were moving in a revolutionary direction, but still hadn’t reached the conclusion that they would have to break with Serrati’s party.

At that congress, in his report on the world economic situation, Trotsky painted the picture of the ebb in the revolutionary movement and affirmed the necessity of conquering the masses by proposing a united front to achieve transitional demands and fight against fascism.

The Comintern realised that the workers outside the PCI had no way of understanding the reasons for the split, and that it wouldn’t suffice to declare oneself for the revolution to win them over: they had already heard such rhetoric from Serrati. The Communists needed to carry out concrete actions that would demonstrate the truly revolutionary character of their new party.

Furthermore, the workers had just suffered a historic defeat, for the Italian revolution was betrayed by the leaders of the CGL and the PSI. In the spring of 1921, fascist gangs were already active around the country setting fire to the offices of local trade unions, socialist and communist organisations and workers’ newspapers. The only way the communists could stop them was to propose to the socialist workers to act as a united front.

Bordiga rejected the united front tactic and was against any “compromise” with the socialists. Trotsky polemicised against him, saying: “Preparation for us means the creation of conditions that would guarantee us the sympathy of the vast majority of the masses (...) The idea of substituting the will of the masses with the decisions of the so-called vanguard must be refuted and is not Marxist”, adding “Revolutionary actions cannot be carried out without the masses, but the masses are not constituted of absolutely pure elements.”

Bordiga was the undisputed leader of the PCI at that time: his positions had hegemony in the new party and were shared not only by Gramsci but the entire leadership of the PCI.

It was in this way that the party, even though it declared that it wanted to conquer the masses, opposed the united front tactic, maintaining that the only way to expose the betrayals of the socialists was to refuse any and all collaboration with them. At most they would accept a united front in the trade unions, but not on the political plane of the class struggle.

With this attitude the PCI contributed to the victory of the fascist gangs. When the “Arditi del Popolo” (organs of anti-fascist struggle) were created, with the intention of fighting the advent of fascism in the streets, they generated enthusiasm amongst the workers and attracted more and more socialists and communists, as well as entire local trade union branches. The disdainful attitude of the PCI leadership, against the advice of the Comintern, was to threaten all PCI members who joined the Arditi del Popolo with expulsion from the party.

Bordiga had illusions that the party could stop the advent of fascism by relying solely on its own organised forces and militants. Defeat was inevitable.

Gramsci begins the struggle against sectarianism

Between May 1922 and May 1924, Gramsci was sent abroad (first to Moscow, then to Vienna) to partake in the executive organs of the Comintern. In that period he had the chance to rethink some positions he had previously adopted, in part thanks to the intense debates he had with the leaders of the Comintern.

He considered January 1921, the date of birth of the PCI, to be the “most critical moment, both of the general crisis of the Italian bourgeoisie, and of the crisis of the workers’ movement. The split, while historically necessary and inevitable, found the broad masses unprepared and reluctant.”

Thus he began to polemicise against Bordiga, criticising his conception of the party, which was provoking an increasingly clear separation from the masses.

He refused to sign an appeal launched by Bordiga, where Bordiga attacked the Comintern for trying to unify the PCI with the internationalist faction in the PSI (the so-called “terzini”). Bordiga’s appeal was supported by Palmiro Togliatti.

In December 1923, Gramsci advanced the idea of forming a “centre” faction in the PCI, which would oppose both Bordiga’s extreme sectarianism and the right-wing positions of Angelo Tasca. The struggle against the Bordighist faction began at the Como Conference of 1924 and culminated at the Lyon Congress of 1926.

At this Congress, the theses presented by Gramsci and approved by over 90% of the party, affirmed that:

- the Italian socialist revolution should be led by the industrial and agricultural working classes, and the peasants of the entire country;

- the working class assumes the leadership of the revolutionary process, at the head of the broad masses;

- the transformation of society is a process that requires a revolutionary rupture from the current system, that is to say a mass insurrection prepared and organised by the party;

- the defeat of the workers in the red biennium was attributed to the absence of a revolutionary party

- the PCI must conquer the majority of the working class by struggling within the mass organisations for immediate demands and goals that would be comprehensible to the broad masses. This is the only way to mature their consciousness and provoke their rupture from the reformist organisations.

- the united front is the fundamental instrument in this struggle; in the objective situation, this tactic is to be applied with the demand of a workers’ and peasants’ government

The new strategy of the party was based on the theses from the first four congresses of the Comintern: it assimilated its orientations and applied them to the concrete situation in Italy.

This is broadly speaking true, although the theses retain some sectarian statements towards the maximalists (the PSI centrists around Lazzari and Serrati) and the reformists, who are presented as the left of the bourgeois forces rather than the right wing of the workers’ movement.

Furthermore, the slogans have a rather reformist character, instead of being transitional demands towards a socialist society.

However, the greatest limitation of Gramsci’s position at the Lyon Congress was that he openly supported the ambiguous international campaign for the “Bolshevisation” of the party. This was not understood, as it had been in the early years of Soviet power, as a campaign for the education of the young Communist Parties on the basis of the Russian experience, but understood as an administrative struggle, with disciplinary methods taken against “factionalism” and witch-hunts against political opponents, supporting disciplinary measures and expulsions very light-heartedly.

This can only be understood in the context of the degeneration of the Comintern following Lenin’s death. The International, ever more firmly in the grasp of the Stalinists, began a campaign of slanders and threats against the Left Opposition and against Trotsky in particular.

This is not the moment to analyse in detail the reasons of this degeneration, for which we recommend Trotsky’s writings including “Stalinism and Bolshevism”, “In Defence of October” and “The Workers’ State, Thermidor and Bonapartism.”

However, Gramsci, despite the climate that was developing internationally, and despite the underground conditions the PCI was forced to work in, still continued to defend the right of factions to organise in the party (a right the PCI contested throughout its entire existence).

Gramsci’s attitude towards Stalinism

Shortly before his arrest in 1927, Gramsci wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the CPSU on behalf of the PCI, which can help us understand his attitude towards the ongoing struggle within the Bolshevik Party.

While Gramsci does not explicitly address the questions on the agenda in the USSR at the time, most of his positions in this letter do not align him with the Left Opposition.

However, he defended the Left Opposition against the ongoing witch-hunt, which was paving the way for the suppression of any kind of democracy in the party.

In the climate which had settled in internationally, Gramsci went against the stream by defending Trotsky and the Left Opposition against the expulsions and recognised his role (together with Zinoviev and Kamenev) as great revolutionaries and teachers, which is no small feat considering that in that moment those leaders were being slandered as counterrevolutionaries.

Togliatti, who in that period was in Moscow, in fact did everything in his power to block this letter by Gramsci and was diametrically opposed to his positions. He thought the PCI should have no reservations in siding with the majority in the CPSU. Gramsci’s reply to Togliatti is harsh:

“(...) we would be pitiful and irresponsible revolutionaries if we simply let events run their course, justifying their necessity a priori (...) Your way of reasoning has made the most pathetic impression on me.”

In summary, we can say that even though Gramsci does bear some responsibility for the bureaucratisation of the International and the Italian party, we must also recognise the independence of his judgment and, in the final analysis, his refusal to adopt a monolithic conception of the party, where dissent was simply to be crushed.

In this regard, the differences between him and Togliatti, who took on the leadership of the PCI when Gramsci was arrested, are enormous.

The bureaucratisation of the PCI and the expulsion of the “three”

Togliatti was happy to simply execute the Stalinist line, transforming the party ever more into an instrument of the Soviet bureaucracy’s foreign policy. This process was aided by the fact that the Stalinist leadership could boast of the prestige of the October Revolution, and by the extreme difficulty that PCI members had in receiving accurate information on what was actually happening in the USSR, given that they had to work underground.

In 1928 the Comintern adopted the policy of “social fascism”, also known as The Third Period. The core of this theory is that on the international scale, a new wave of revolutionary movements was coming, and that the main enemy in this context were the reformist and socialist parties, particularly the more left-wing ones, who played the role of fifth columns of imperialism in the workers’ movement.

According to a famous speech by Molotov at a Congress of the Comintern, fascists and socialists were “twins”: from there originated the moniker given to reformists as “social fascists.”

This theory was false in all of Europe; Trotsky refuted it in “The ‘Third Period’ of the Comintern’s Mistakes”.

But in the case of Italy, this theory was even more ridiculous. To declare that a pre-revolutionary situation was about to begin, with fascism in power, when Mussolini had a strong base of support, the proletarian masses were inert and the PCI had a very small network of underground militants, with some of the main leaders in jail, was completely divorced from the objective situation.

In 1930, in fact, an opposition to Togliatti’s line began to form, led by three of the seven members of the PCI’s Politburo. Tresso, Leonetti and Ravazzoli opposed the theory of social fascism, advocating instead the positions taken by Trotsky and the International Opposition.

The “three” supported many of the fundamental elements of the Lyon Theses against the sectarian turn of the PCI under Bordiga’s leadership. But in the debate, Togliatti resorted to insults instead of arguments, and the three were rapidly expelled, together with thirty or so other leading figures in the party.

According to the testimony of some of his comrades, it would appear that Gramsci was negatively affected by the expulsion of the three. Tresso had been one of his favourite mentees, but perhaps the thing that troubled him the most was that he shared some of the opinions of the expelled comrades.

The PCI itself admitted in the 1960s that Gramsci in that period would not have shared the positions of the party and of the Comintern. According to a report written by a party activist, Athos Lisa, in 1933, Gramsci viewed indignantly the superficial judgment of some communists who saw the collapse of fascism as imminent and believed Italy would transition seamlessly from a fascist dictatorship to a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Gramsci’s brother, Gennaro, would testify many years later that Antonio agreed with Leonetti, Tresso and Ravazzoli, did not defend their expulsion, and did not accept the line of the Comintern. According to a testimonial by Sandro Pertini, Gramsci did not agree with the idea of “social fascism” either.

It is not a coincidence, in fact, that in an essay written in prison, Gramsci formulated the demand for a Constituent Assembly to be elected on the basis of universal suffrage, direct and secret ballots, open to citizens of both sexes aged 18 and above, which was the same demand the three indicated in a letter they wrote to Trotsky in 1930.

In his reply to this letter, Trotsky wrote “it is precisely with the aid of these transitional slogans, from which the need of a proletarian dictatorship emerges, that the communist vanguard will have to conquer the entirety of the working class and that the latter will have to unify around itself all the exploited masses of the nation.”

In fact, Trotsky and Gramsci were the only two leaders internationally who were able to give a valid characterisation of fascism, not only as capitalist reaction, but as a mass movement of the urban and rural petit bourgeoisie aimed at violently smashing the organised workers’ movement, from its parties to its trade unions, and even its cooperatives and recreational circles.

We cannot know what would have happened if Gramsci had not been in prison during the Third Period turn; perhaps he would have joined the Left Opposition, or perhaps he would have made an appeal for “party unity” as he had done in 1926.

The point is, however, that Gramsci, in terrible conditions, isolated and with extreme difficulties in receiving information, developed a position that was much more correct than that of the Comintern leaders who were immersed in the political struggle and had at their disposal the experience and information provided by several mass parties to help them in their orientation.

This is telling of Gramsci’s political greatness, but also of the disasters of Stalinism in the workers’ movement.

The Prison Notebooks

In the ten years he spent in prison, Gramsci wrote extensively. The Prison Notebooks, published for the first time in 1948, were written by Gramsci under surveillance from fascist censorship. Because of this, the language he is forced to use is often ambiguous and has a more sociological and not political character. In fact, the Gramsci of the Prison Notebooks is very different from the Gramsci of The New Order or the Lyon Theses.

There are nonetheless extremely interesting reflections in the Notebooks that have been used (particularly by the PCI leaders in the postwar period) to claim that Gramsci was in the process of developing a gradualist conception of the seizure of political power by the workers.

The most controversial element in this sphere is the interpretation of the concept of hegemony.

First and foremost, it must be said that the concept of hegemony is not exclusively a Gramscian one, as it was part of the theoretical heritage of Russian Social Democracy already at the beginning of the 20th century.

The word “hegemony” is also used in the Theses from the Third Congress of the Comintern, in the sense of the proletariat assuming the leading role at the helm of the movement of all oppressed classes in the struggle against capital.

In a passage from the Theses from the Fourth Congress the concept is extended and the term “hegemony” is used to define the supremacy that the bourgeoisie has over the proletariat under capitalism.

That is the only example of the term hegemony being used in that sense, and in some ways that was Gramsci’s starting point, from which he would develop a profound reflection on the bourgeois hegemony over the working classes.

The question that Gramsci attempts to analyse is what character the revolution should have in the West, where the bourgeoisie was indisputably more consolidated and entrenched than its Russian counterpart, and had built up a network of mechanisms to exercise social control, but also to garner consensus from the workers themselves. According to Gramsci: “In the East, the State was everything, civil society was primordial and gelatinous; in the West, there was a proper relationship between State and civil society, and when the State trembled a sturdy structure of civil society was at once revealed. The State was only an outer ditch, behind which there was a powerful system of fortresses and earthworks (…)”

What revolutionary strategy is necessary for the West? Gramsci considers a “war of movement”, used in the Russian Revolution, impractical and maintains that the correct tactic is a “war of position”. He declares that Lenin had also reached this conclusion and that the united front tactic was Lenin’s response to this question.

In this regard he criticises Trotsky, in our opinion unfairly, when defining the theory of permanent revolution, the theory of the war of movement and of the frontal collision on the political and military front. Gramsci incorrectly equates Trotsky to Bordiga and the German Communists, who in March 1921 carried out an insurrection without the support of the masses, which led to enormous losses and a consequent defeat of the German Communist Party (KPD), who paid an incredibly high price for this putschist behaviour.

This demonstrates that Gramsci had probably never read “The Permanent Revolution”. His interpretation of the theory is arbitrary at best, if we consider that Trotsky was together with Lenin one of the main architects of the united front tactic, that he criticised sharply the sectarian behaviour of the German Communists in March 1921, and as his military writings show, was also opposed to the “offensive theorists” like Frunze and Tukhachevsky on the military plane.

But, apart from the fact that in pre-revolutionary Russia civil society wasn’t so “gelatinous” after all, Gramsci is actually asking himself a question that cannot easily be answered in isolation in his Turi prison. In fact, he will never give a definitive answer to the problem of the revolution in the West.

Certainly one of the key elements of his reflections is the question of consensus. At one point in the Notebooks, Gramsci seems to claim (although there are contradictory passages) that in the West the party must conquer a wider consensus than in 1917 Russia because the enemy is much stronger and governs more through consensus than coercion. In a sense, this is without doubt true in a parliamentary democracy, even though consensus and coercion are two sides of the same coin that the bourgeois use to maintain their control, alternating them according to the situation.

The same is true of the revolution. In the revolutionary process, the working class becomes the hegemonic power in society but the winning of consensus must necessarily be combined with the use of force (naturally, on a mass basis and not of an individual character: the force of a majority against a minority) against the forces of reaction hostile to the revolution.

The fact that the working class must win the consensus of the majority of the population, in some cases even by granting concessions to the middle classes once in power (the example of the NEP demonstrates this) does not mean that the transformation of society mustn’t happen in a revolutionary way through an insurrection.

This classic Marxist conception of the state isn’t questioned anywhere in the Notebooks and that is the proof of the revolutionary and communist nature of Gramsci’s thought.

It should be added to this that Gramsci’s conception of the party is the typical one of a revolutionary party made up of educated Marxist cadres. When he talks about a party completely made up of intellectuals, he doesn’t mean, obviously, that its doors should be shut to the workers or to the masses in general. He is referring to a party with a high political level, not simply made up of members on paper but conscious militants who participate and contribute to every aspect of party activity.

But Gramsci also has the huge merit of having provided us with a history of the Italian Risorgimento from a proletarian point of view, against the rhetoric of the unification of Italy given by the bourgeois, unlike Marx and Engels who, knowing little of the Italian reality, were very limited in this sense, especially in the criticism of the counterrevolutionary role played in the Risorgimento by the democrats Mazzini and Garibaldi, who were initially members of the First International.

Gramsci gives a merciless analysis of the subordination of Garibaldi and the democrats to the liberals led by Cavour and the monarchy. The Risorgimento was a bourgeois revolution that was not completed because of the cowardice of the Italian bourgeoisie who did not have the courage to get rid of the King and the nobility.

Because of its late entry onto the global stage and because of its economic weakness, the Italian bourgeoisie was very different to the French Jacobins and, instead of attacking the aristocracy head-on, decided in the end to ally itself with it. The democrats submitted to this alliance and, in the final analysis, helped carry it out.

In fact, when the poor peasants, riding the wave of the arrival of Garibaldi’s “Mille” [Thousand] in Sicily, decided to occupy the land of the big landowners, carrying out one of the main tasks of the bourgeois revolution, they were massacred not by the Bourbons but by the troops of Garibaldi and Bixio themselves.

This historic betrayal lies at the root of the underdevelopment of southern Italy, from which according to Gramsci flowed the inability of the bourgeois to solve the agrarian question. This problem could only be solved by a socialist revolution, through an alliance between the proletariat and the peasants, an alliance on which the revolution had to rest. Thus for Gramsci, the problem of the underdeveloped south could not be solved under capitalism.

It is astonishing how these reflections are so relevant today, and what little audience they find in the Italian left, who celebrate Gramsci but without truly understanding his profound revolutionary message.

First published in FalceMartello n° 116, 19-5-1997

No comments:

Post a Comment