By Subhankar banerjee, The Nation, July 30, 2015

|

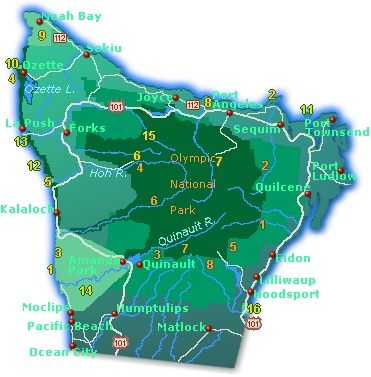

| Olympic National Park in Washington State |

The wettest rainforest in the continental United States had gone up in flames and the smoke was so thick, so blanketing, that you could see it miles away. Deep in Washington’s Olympic National Park, the aptly named Paradise Fire, undaunted by the dampness of it all, was eating the forest alive and destroying an ecological Eden. In this season of drought across the West, there have been far bigger blazes but none quite so symbolic or offering quite such grim news. It isn’t the size of the fire (though it is the largest in the park’s history), nor its intensity. It’s something else entirely—the fact that it shouldn’t have been burning at all. When fire can eat a rainforest in a relatively cool climate, you know the Earth is beginning to burn.

And here’s the thing: the Olympic Peninsula is my home. Its destruction is my personal nightmare and I couldn’t stay away.

SMOKE GETS IN MY EYES

“What a bummer! Can’t even see Mount Olympus,” a disappointed tourist exclaimed from the Hurricane Ridge visitor center. Still pointing his camera at the hazy mountain-scape, he added that “on a sunny day like this” he would ordinarily have gotten a “clear shot of the range.” Indeed, on a good day, that vantage point guarantees you a postcard-perfect view of the Olympic Mountains and their glaciers, making Hurricane Ridge the most visited location in the park, with the Hoh rainforest coming in a close second. And a lot of people have taken photos there. With its more than three million annual visitors, the park barely trails its two more famous Western cousins, Yosemite and Yellowstone, on the tourist circuit.

Days of rain had come the weekend before, soaking the rainforest without staunching the Paradise Fire. The wetness did, however, help create those massive clouds of smoke that wrecked the view miles away on that blazing hot Sunday, July 19. Though no fire was visible from the visitor center—it was the old-growth rainforest of the Queets River Valley on the other side of Mount Olympus that was burning—massive plumes of smoke were rising from the Elwha River and Long Creek valleys.

By then, I felt as if smoke had become my companion. I had first encountered it on another hot, sunny Sunday two weeks earlier.

On July 5, I had gone to Hurricane Ridge with Finis Dunaway, historian of environmental visual culture and author of Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images. As this countryside is second nature to me, I felt the shock and sadness the moment we piled out of the car. In a season when the meadows and hills should have been lush green and carpeted by wildflowers, they were rusty brown and bone-dry.

Normally, even when such meadows are still covered in snow, glacier lilies still poke through. Avalanche lilies burst into riotous bloom as soon as the snow melts, followed by lupines, paintbrushes, tiger lilies, and the Sitka columbines, just to begin a list. Those meadows with their chorus of colors are a wonder to photograph, but the flowers also provide much needed nutrition to birds and animals, including the endemic Olympic marmots that prefer, as the National Park Service puts it, “fresh, tender, flowering plants such as lupine and glacier lilies.”

Snow normally lingers on these subalpine meadows until the end of June or early July, but last winter and spring were “anything but typical,” as the summer issue of the park’s quarterly newspaper, the Bugler, pointed out. January and February temperatures at the Hurricane Ridge station were “over six degrees Fahrenheit warmer than average.”

By late February, “less than three percent of normal” snowpack remained on the Olympic Mountains and the meadows, normally still covered by more than six feet of snow, “were bare.” As the Bugler also noted, recent data and scientific projections suggest that “this warming trend with less snowpack is something the Pacific Northwest should get used to… What does this mean for summer wildflowers, cold-water loving salmon, and myriad animals that depend on a flush of summer vegetation watered by melting snow?” The answer, unfortunately, isn’t complicated: it spells disaster for the ecology of the park.

Move on to the rainforest and the news is no less grim. This January, it got 14.07 inches of precipitation, which is 26 percent less than normal; February was 17 percent less; March was almost normal; and April was off by 23 percent. Worse yet, what precipitation there was generally fell as rain, not snow, and the culprit was those way-higher-than-average winter temperatures. Then the drought that already had much of the West Coast in its grip arrived in the rainforest. In May, precipitation fell to 75 percent less than normal and in June it was a staggering 96 percent less than normal, historic lows for those months. The forest floor dried up, as did the moss and lichens that hang in profusion from the trees, creating kindling galore and priming the forest for potential ignition by lightning.

That day, I was intent on showing Finis the spot along the Hurricane Hill trail where, in 1997, I had taken a picture of a black-tailed deer. That photo proved a turning point in my life, winning the Slide of the Year award from the Boeing photography club and leading me eventually to give up the security of a corporate career and start a conservation project in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

As it happened, it wouldn’t be a day for nostalgia or for seeing much of anything. On reaching Hurricane Hill, we found that the Olympic Mountains were obscured by smoke from the Paradise Fire. Meanwhile, looking north toward the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the Salish Sea, all that we could see was an amber-lit deep haze. More smoke, in other words, coming from more than 70 wildfires burning in British Columbia, Canada. As I write this, there are 14 active wildfires in Washington and five in Oregon, while British Columbia recently registered 185 of them.

So if you happen to live in the drought-stricken Southwest and are dreaming of relocating to the cool, moist Pacific Northwest, think again. On the Olympic Peninsula, it’s haze to the horizon and the worst drought since 1895.

A RAINFOREST IN A NATIONAL PARK

For visitors to the Olympic Peninsula, it seems obvious that a temperate rainforest—itself a kind of natural wonder—should be in a national park. As it happens, getting it included proved to be one of the most drawn-out battles in American conservation history, which makes seeing it destroyed all the more bitter.

Two centuries ago, expanses of coastal temperate rainforests stretched from northern California to southern Alaska. Today, only about 4 percent of the California redwoods remain, while in Oregon and Washington, the forests are less than 10 percent of what they once were. Still, even in a degraded state, this eco-region, including British Columbia and Alaska, contains more than a quarter of the world’s remaining coastal temperate rainforest.

In the era of climate change, this matters, because the Pacific coastal rainforest is so productive that it has a much higher biomass than comparable areas of any tropical rainforest. In translation: The Pacific rainforests store an impressive amount of carbon in their wood and soil and so contribute to keeping the climate cool. However, when that wood goes up in flames, as it has recently, it releases the stored carbon into the atmosphere at a rapid rate. The massive plumes of smoke we saw at Hurricane Ridge offer visual testimony to a larger ecological disaster to come.

The old-growth rainforest that stretches across the western valleys of the Olympic National Park is its crown jewel. As UNESCO wrote in recognizing the park as a World Heritage Site, it includes “the best example of intact and protected temperate rainforest in the Pacific Northwest.” In those river valleys, annual rainfall is measured not in inches but in feet, and it’s the wettest place in the continental United States. There you will find living giants: a Sitka spruce more than 1,000 years old; Douglas fir more than 300 feet tall; mountain hemlock at 150 feet; yellow cedars that are nearly 12 feet in diameter; and a Western red cedar whose circumference is more than 60 feet.

The rainforest is home to innumerable species, most of which remain hidden from sight. Still, while walking its trails, you can sometimes hear the bugle or get a glimpse of Roosevelt elk amid moss-draped, fog-shrouded bigleaf maples. (The largest herd of wild elk in North America finds refuge here.) And when you do, you’ll know that you’ve entered a Tolkienesque landscape. Those elk, by the way, were named in honor of President Theodore Roosevelt who, in 1909, protected 615,000 acres of the peninsula, as Mount Olympus National Monument.

Why not include a rainforest in a national park? That was the question being asked at the turn of the 20th century and Henry Graves, chief of the US Forest Service, answered it in definitive fashion this way: “It would be great mistake to include in parks great bodies of commercial timber.”

Despite the power of the timber industry and the Forest Service, however, five committed citizens with few resources somehow managed to protect the peninsula’s last remaining rainforest. “They did it by involving the public,” environmentalist and former park ranger Carsten Lien writes in his Olympic Battleground: Creating and Defending Olympic National Park. He adds, “Preserving the environment through direct citizen activism, as we know it today, had its beginnings in the Olympic National Park battle.”

In 1938, the national monument was converted to Olympic National Park and a significant amount of rainforest was included. As Lien would discover in the late 1950s, however, the Park Service, despite its rhetoric of stewardship, continued to let timber interests log there. Today, such practices are long past, though commercial logging continues to play a significant part in the economy of the peninsula in national, state, and private forests.

A FIRE THAT JUST WON’T STOP

Once the fire began, I just couldn’t keep away. On a rainy July 10, for instance, listening to James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain,” I drove toward the Queets River Valley to learn more about the Paradise Fire so that I could “talk about things to come.”

At the Kalaloch campground, I asked the first park employee I ran into whether the rain, then coming down harder, might extinguish the fire? “It will slow down the fire’s spread,” she told me, “but won’t put it out. There’s too much fuel in that valley.”

The next morning, with the rain still falling steadily and the fire still burning, I stood at the trailhead to the valley thinking about what another park employee had told me. “The sad thing,” she said, “is that the fire is burning in the most primitive of the three river valleys.” In other words, I was standing mere miles away from the destruction of one of the most primeval parts of the forest. As Queets was also one of the more difficult locations to visit, less attention was being given to the fire than if, say, it were in the always popular Hoh valley.

In a sense, the Paradise Fire has been burning out of sight of the general public. Information about it has been coming from press releases and updates prepared by the National Park Service. Though it is doing a good job of sharing information, environmental disasters and their lessons often sink in most deeply when they are observed and absorbed into collective memory via the stories, fears, and hopes of ordinary citizens.

I had breakfast at the Kalaloch Lodge restaurant, not far from the Queets,while the rain was still falling. “When will the sun come out?” an elderly woman at the next table asked the waitress as if lodging a complaint with management. “The whole weekend we’ve been here it’s rained continuously.”

“I’m so happy that finally we got three days of rain,” the waitress responded politely. “This year we got 12 inches. Usually we get about 12 feet. It’s been bad for trees and all the life in our area.” In fact, the peninsula has received over 51 inches of rain, mostly last winter, but her point couldn’t have been more on target. “It has been so dry that the salmon can’t move in the river,” she added. Her voice lit up a bit as she continued, “With this rain, the rivers will rise and the salmon will be able to go upriver to spawn. The salmon will return.”

I asked where she was from. “Quinault Nation,” she said, citing one of the local native tribes dependent both nutritionally and culturally on those salmon.

“The Queets, the largest river flowing off the west side of the Olympics, is running at less than a third its normal volume,” the Seattle Times reported. “[B]ad news for the wild salmon runs, steelhead, bull trout, and cutthroat trout.” In addition to the disappearing snowpack and severe drought, the iconic glaciers of the Olympic Mountains are melting rapidly, which will likely someday spell doom for the park’s rivers and its vibrant ecology. According to Bill Baccus, a scientist at the park, over the last 30 years, those glaciers have shrunk by about 35 percent, a direct consequence of the impact of climate change.

After breakfast, I took off for the Hoh Valley. At its visitor center, a ranger described the battle underway with the Paradise Fire. Summing up how dire the situation was, he said, “Our goal is confinement, not containment.” Normally, success in fighting a wildfire is measured by what percentage of it has been contained, but not with the Paradise.

“Safety of the firefighters and safety of the human communities are our two priorities right now,” the ranger explained. As a result, the National Park Service is letting the fire burn further into wilderness areas unfought, while trying to stop its spread toward human communities and into commercially valuable timberlands outside the park.

For firefighters, combating such a blaze in an old-growth rainforest with steep hills is, at best, an impossibly dangerous business. Large trees are “falling down regularly,” firefighter Dave Felsen told the Seattle Times. “You can hear cracking and you try to move, but it’s so thick in there that there is no escape route if something is coming at you.”

Besides, many of the traditional means of fighting wildfires don’t work against the Paradise. Dumping water from a helicopter, to take one example, is almost meaningless. As an NPR reporter noted, the rainforest canopy “is so dense that very little of the water will make it down to the fire burning in the underbrush below.” Worse yet, as The Washington Post reported, the large trees and thick growth “make it impossible to effectively cut a fire line” through the foliage to contain the spread of the flames.

With the moist lichens and mosses that usually give the rainforest its magical appearance shriveled and dried out, they now help spread the fire from tree to tree. When they burst into flames and fall to the ground, yet more of the dry underbrush catches, too. In other words, that forest, which normally would have suppressed a fire, has now been transformed into a tinderbox.

“Few people in our profession have ever seen this kind of fire in this kind of ecosystem,” Bill Hahnenberg, the Paradise Fire incident commander, told his crew. “The information you gather could be really valuable.” He didn’t have to add the obvious: its value lies in offering hints as to how to fight such fires in a future that, as the region becomes drier and hotter, will be ever more amenable to them.

So far, the fire is smoldering, but as the summer heats up, the Seattle Times reports, “there is still the potential for a crown fire that can spread in dramatic fashion as treetops are engulfed in flames.” According to several park employees I spoke with, the Paradise Fire is likely to burn until the autumn rains return to the western valleys. As of July 23, it had eaten 1,781 acres, which sounds modest compared to other fires burning in the West, but you have to remind yourself that it’s not modest at all, not in a temperate rainforest. It also poses a challenge to the very American idea of land conservation.

Throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, American environmentalists passionately fought to protect large swaths of public lands and waters. The national parks, monuments, wildlife refuges, and wildernesses they helped to create laid the basis for a new American identity. Nationalism aside, such publicly protected lands and waters also offered refuge for an incredible diversity of species, some of which would have otherwise found it difficult to survive at the edges of an expanding industrialized, consumerist society. Today, that diversity of life within these public lands and waters is increasingly endangered by climate change.

What, then, should environmental conservation look like in a twenty-first century in which the Paradise Fire could become something like the norm?

TANKERS AND RIGS

“This is not an anthropogenic fire,” the ranger I spoke with at the Hoh visitor center insisted. In the most literal sense, that’s true. In late May, lightning struck a tree in the Queets Valley and started the fire, which then smoldered and slowly spread across the north bank of the river. It was finally detected in mid-June and firefighters were called in. That such a lightning strike disqualifies the Paradise Fire from being “anthropogenic”—human-caused—would once have been a given, but in a world being heated by the burning of fossil fuels, such definitions have to be reconsidered.

The very rarity of such fires speaks to the anthropogenic nature of the origins of this one. After all, a temperate rainforest is a vast collection of biomass and so a carbon sink is only possible thanks to the rarity of fire in such a habitat. According to the World Wildlife Fund, “With a unique combination of moderate temperatures and very high rainfall, the climate makes fires extremely rare” in such forests.

The natural fire cycle in these forests is about 500 to 800 years. In other words, once every half-millennium or more this forest may experience a moderate-sized fire. But that’s now changing. Mark Huff, who has been studying wildfires in the park since the late 1970s, told Seattle’s public radio station KUOW that in the past half-century there have already been “three modest-sized fires” here, including the Paradise, though the other two were less destructive. According to a National Park Service map (“Olympic National Park: Fire History 1896–2006”) in the Western rainforest, during that century-plus, two lightning-caused fires burned more than 100 acres and another more than 500 acres.

If, however, fires in the rainforest become the new normal, comments Olympic National Park wildlife biologist Patti Happe, “then we may not have these forests.”

A team of international climate change and rainforest experts published a study earlier this year warning that, “without drastic and immediate cuts to greenhouse gas emissions and new forest protections, the world’s most expansive stretch of temperate rainforests from Alaska to the coast redwoods will experience irreparable losses.” In fact, says the study’s lead author, Dominick DellaSala, “In the Pacific Northwest…the climate may no longer support rainforest communities.”

Speaking of the anthropogenic, on our way back, Finis and I stopped in Port Angeles, the largest city on the peninsula. There we noted a Chevron oil tanker, the massive 904-foot Pegasus Voyager, moored in its harbor on the Salish Sea. It had arrived empty for “topside repair.” Today, only a modest number of oil tankers and barges come here for repair, refueling, and other services, but that could change dramatically if Canada’s tar sands extraction project really takes off and vast quantities of that particularly carbon-dirty energy product are exported to Asia.

That industry is already fighting to build two new pipelines from Alberta, the source of most of the country’s tar sands, to the coast of British Columbia. “Once this invasion of tar sands oil reaches the coast,” a Natural Resources Defense Council press release states, “up to 2,000 additional barges and tankers would be needed to carry the crude to Washington and California ports and international markets across the Pacific.” All of those barges and tankers would be moving through the Salish Sea and along Washington’s coast.

And let’s not forget that, in May, Shell Oil moored in Seattle’s harbor the Polar Pioneer, one of the two rigs the company plans to use this summer for exploratory drilling in the Chukchi Sea of Arctic Alaska (a project only recently green-lighted by the Obama administration). In fact, Shell expects to use that harbor as the staging area for its Arctic drilling fleet. The arrival of the Polar Pioneer inspired a “kayaktivist” campaign, which received national and international media coverage. It focused on drawing attention to the dangers of drilling in the melting Arctic Ocean, including the significant contribution such new energy extraction projects could make to climate change.

In other words, two of the most potentially climate-destroying fossil fuel–extraction projects on Earth more or less bookend the burning Olympic Peninsula.

The harbors of Washington, a state that prides itself on its environmental stewardship, have already become a support base for one, and the other will likely join the crowd in the years to come. Washington’s residents will gradually become more accustomed to oil rigs and tankers and trains, while its rainforests burn in yet more paradisical fires.

In the meantime, the Olympic Peninsula is still wreathed in smoke, the West is still drought central, and anthropogenic is a word all of us had better learn soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment