By Gabriel Levy, People and Nature, June 20, 2014

|

| BP Deep Water Horizon platform in Gulf of Mexico exploded on April 20, 2010 |

Humanity’s problem is not that it will use up all the coal, oil and gas. That could not happen for hundreds of years. But, already, the easy-to-get-at resources are running out. Oil and gas companies are going further, drilling deeper, and using more and more complex technologies to eke out resources, than ever before.

And long before these fuels are exhausted, the world’s economies will have burned the amount that – according to climate scientists – can be used without potentially triggering uncontrollable global warming.

These are some of the conclusions of a report published yesterday by Corporate Watch, To The Ends Of The Earth. It explains the drivers behind the “unconventional fuels” boom, what those fuels are, and why there is a groundswell of opposition to them by communities and environmentalists.

The report questions the idea of “peak oil”, i.e. that oil production would reach a maximum, and then decline, causing “the imminent collapse of modern civilization”.

The stock of conventional oil and gas reserves – that is, those that it is economically feasible to produce, using conventional drilling techniques – may indeed be peaking, it argues. But rather than this causing “global economic and social collapse”, it is driving the oil producers to access new resources that were previously considered too expensive, or too difficult to make use of.

“As oil and gas reserves begin to run low, energy prices rise, and this, along with enormous power held by fossil fuel companies, means that new, more extreme methods of production are being found to sustain our society’s addiction to fossil fuels”, the report says (p. 8). Governments’ preference for reducing their dependence on imported energy is also a factor driving “unconventional” oil and gas.

The report explains how the definition of “unconventional” fossil fuels changes over time. It applies to resources that require more extreme methods to produce, such as tar sands and shale oil and gas. But as the methods are developed and made more cost-effective, they become “conventional”.

For example, offshore deep-water oil deposits – such as those that were being produced by BP’s Deep Water Horizon rig when it exploded in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 – used to be regarded as “unconventional”, but are now drilled routinely.

In the Caspian Sea, BP and its partner companies are exploring oil and gas fields that are not only under a kilometre of water and several kilometres of rock, but are also held in by pressures greater than that of any hydrocarbons ever produced.

“Unconventional” fossil fuels tend to have a greater environmental impact, as they are more spread out geographically. And they have a lower Energy Return on Investment (EROI) ratio – that is, you have to put in more energy just to get fuels containing the same amount of energy out.

“Unconventional fossil fuels generally have lower EROI values than conventional ones”, the report points out (p. 10). “However, EROI values for conventioanl fossil fuels are also going down, as the deposits that are easiest to exploit are being used up and production moves to greater depths and more extreme environments.

“Moving towards lower EROI energy sources means committing a larger proportion of the economy to producing energy. A worrying consequence is that this will likely further increase the already enormous power held by the fossil fuel companies.”

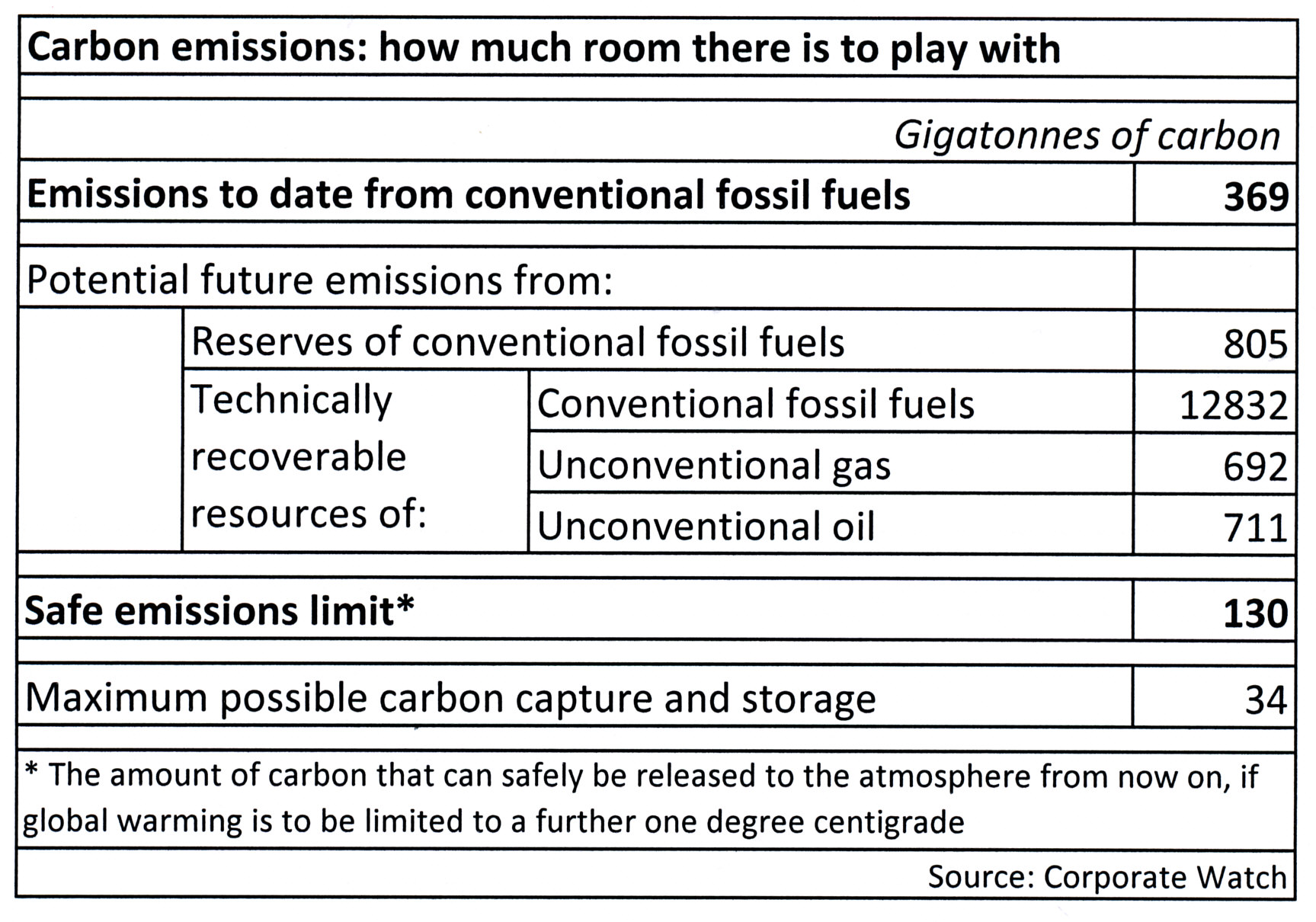

A sobering graphic (p. 15) compares the carbon content of the total stock of fossil fuels already burned, of reserves (i.e. coal, oil and gas estimated to be recoverable as the economics stand), and of technically recoverable resources. It’s worth repeating the numbers:

The “safe emissions limit” is the amount of carbon that could safely be burned from now, in order to limit further global warming to one degree centigrade, the level deemed acceptable by a group of scientists headed by James Hansen, one of the world’s pioneer climate researchers (reported here).

In the chart, the “maximum possible carbon capture and storage” number reflects researchers’ estimates of the maximum possible carbon that could be sequestered (i.e. effectively buried, to prevent it going into the atmosphere) by 2050, if carbon capture and storage technology – which is still under development – is successfully made use of.

What this graphic shows particularly clearly is that most conventional fossil fuel reserves – let alone the vast stock of technically recoverable resources, including “unconventional” ones – need to be left in the ground, if humanity is to be assured of avoiding dangerous climate change.

Corporate Watch’s report contains a series of fact sheets explaining what each of the most significant “unconventional” fossil fuels are, and what sort of campaigns have been waged over their extraction. The topics covered are: shale gas (tight gas); tar sands; coal bed methane; underground coal gasification; oil shale; shale oil (tight oil); coal and gas to liquids; methane hydrates; other unconventional fossil fuels; and carbon capture and storage. Download it here!

No comments:

Post a Comment