By Jeff Mackler, Socialist Action, November 27, 2013

|

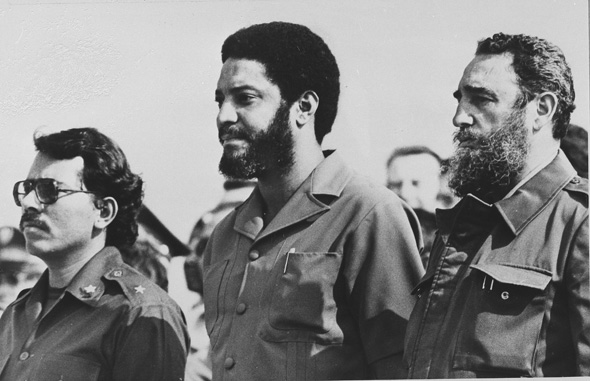

| Maurice Bishop (center), with Daniel Ortega and Fidel Castro in Havana |

Thirty years ago, on Oct. 25, 1983, almost 8000 U.S. Rangers invaded the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada to make doubly sure that the revolution of March 13, 1979, four and a half years earlier, would not rise again. This vital and exemplary revolution in a Black, English-speaking country of 100,000 nevertheless posed a serious threat to U.S. imperialism. This was not because of the size or military power of this tiny nation that measured some 21 by 11 miles but because of the politics and socialist orientation of its leadership.

In truth, however, the revolution had ended in blood a week earlier. At that time, a Stalinist “leader” of Grenada’s governing party, the New Jewel Movement (NJM) and its People Revolutionary Government (PRG), Bernard Coard, ordered a handful of Grenadian soldiers led by Hudson Austin to gun down Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, several other members of Grenada’s central leadership, and some dozen supporters who were part of a demonstration of tens of thousands demanding Coard’s removal.

The subtitle of this article, “A 30-year personal retrospective,” is included because by a combination of circumstances I had become intimately familiar, as a sometimes close observer to be sure, with the events surrounding the revolution’s internal disputes and tragic demise.

Within days of the impending U.S. invasion, and after initiating a San Francisco demonstration of 5000 to warn against it, I resigned from the then most influential and largest Trotskyist party in the U.S., the Socialist Workers Party, where my political loyalties had resided for almost two decades. The SWP’s break from its revolutionary heritage had begun several years earlier, compelling me along with several hundred other comrades to form a short-lived internal opposition. However, we were denied a fundamental right that, since its formation a half-century earlier, had been central to the SWP’s traditions and rich democratic history—the right to present contending ideas to the ranks for thorough discussion, debate, and decision. By 1983 at least half of this opposition of some 200 comrades, including several of the SWP’s founding members, has been bureaucratically expelled.

The SWP’s initial stance on the murder of Maurice Bishop was kept from the membership by the party’s uncertain leadership. A week after Bishop’s murder, when Cuban President Fidel Castro denounced Bishop’s murder and skewed Bernard Coard as a Stalinist betrayer, the SWP reversed course and eventually published a long tract, joining in Castro’s powerful repudiation. But the SWP’s actions before Castro spoke revealed a tragic flaw in the politics and orientation of this once exemplary revolutionary party.

I resigned a few days after the U.S. invasion, to be among the founders of Socialist Action, but not before observing close up—and against the wishes of the SWP leadership—the tragic events surrounding Grenada’s internal travail and disintegration.

The origins of Grenada’s March 13, 1979, revolution are not well known. The 13th of March, an unlucky day in the minds of the superstitious, was chosen by Grenada’s president for a trip to New York City to attend a conference whose agenda focused on flying saucers, the occult, and extra-terrestrial communication. Knighted in 1974 by Great Britain’s queen as Sir Mathew Eric Gairy, the president’s demons extended to literally banning the construction of left turn lanes on the few roads that surrounded this volcanic mountain nation. With half of its people unemployed and living in poverty, and 70 percent of its women workforce unemployed, Grenada’s sneering critics had long derided it as “the armpit of the Caribbean.”

Before Gairy’s departure, he left word for his notorious secret death squad, the Mongoose Gang, to assassinate the young 34-year-old revolutionary, Maurice Bishop, and his comrades, whose New Jewel (Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education and Liberation) Movement and its allied parties had in fact won the previous Grenadian election only to have the results voided at Gairy’s diktat.

But secrets are hard to keep in a small nation like Grenada. A few friends informed Bishop and his comrades of Gairy’s assassination directive. These young revolutionaries, whose choices were limited indeed—most obviously, to flee the island or hide—hastily planned a response that had more than a few stunning, if not unexpected results. Their plan began on March 13 at 4:30 a.m. with an armed assault by Bishop and a relatively small group of supporters on Grenada’s True Blue military barracks, where almost all of Grenada’s tiny army lay asleep. Some 20-50 activists participated, most having had no prior military experience. Gairy’s troops quickly surrendered, taking but a handful of casualties.

Grenada’s sole radio station, instantly renamed Radio Free Grenada, was captured at 10:30 that morning. Bishop delivered his famous address, “A Bright New Dawn,” which included a call to action, stating, “I am now calling upon the working people, the youth, workers, farmers, fishermen, middle-class people, and women to join our armed revolutionary forces at central positions in your communities and to give them any assistance which they may call for.”

The call was initially disregarded by Grenada’s cautious populace for fear that it might be the work of dictator Gairy, seeking to entice unwary Bishop supporters into the streets where they would be met with arrest, if not execution. It was not until the inspired NJM leaders played Bob Marley’s revolutionary music, banned under Gairy, that the masses realized that indeed, this was to be a “bright new dawn” for the Grenadian people.

Bishop’s followers, perhaps 200 activists at most, but accompanied by massive community support across the island, successfully seized control of all local police stations. Bishop’s address to the nation explained a truth that few doubted. “The criminal dictator, Eric Gairy,” he stated, “apparently sensing that the end was near, yesterday fled the country, leaving orders for all opposition forces, including especially the peoples’ leaders to be massacred.

“Before these orders could be followed, the Peoples’ Revolutionary Army was able to seize power. The people’s government will now be seeking Gairy’s extradition so that he may be put on trial to face charges, including the gross charges, the serious charges, of murder, fraud and the trampling of the democratic rights of our people.”

Bishop’s statement made clear the revolution’s objectives: “People of Grenada, this revolution is for work, for food, for decent housing and health services, and for a bright future for our children and great grand-children. … The benefits of the revolution will be given to everyone regardless of political opinion or which political party they support.

“Let us all unite as one. All police stations are again reminded to surrender their arms to the people’s revolutionary forces.”

“Maurice’s boys,” as they were popularly called, in consort with the Grenadian people, had indeed, taken power. With but a handful of deaths, Grenada was deemed “the peaceful revolution” by its friends everywhere.

The newly-founded People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG) soon after sought financial aid from the U.S. and other capitalist nations to meet its promises to the Grenadian people. Aid was denied by the Carter and Reagan administrations, who, seeking to isolate this poor former English colony of Black slaves, pressed other countries to follow suit. The call of Black Power that began in the U.S. had swept the Caribbean and around the world. In Grenada, revolutionary Blacks had achieved power and set out to be an example to the world of what could be achieved by oppressed people, even in an isolated poor nation, under constant threat and virtually embargoed by U.S. imperialism.

A Nov. 19, 1979, Nation magazine interview with Bishop made the new government’s intentions and political origins clear. Said Bishop, “We have always stressed, underlined and emphasized that we are socialist and manifestly so. What we have also said is that the way in which people should define what we mean by socialism is to look at our manifesto, study our programmes and policies [over the past] six and a half years, see what struggles we have defended, see whose interests we have fought for, and from that you can tell see what we are.”

With the solidarity and support of revolutionary-minded volunteers around the world, and especially from Cuba, which several PRG leaders had visited, Grenadians set out to be an example to the world. This was at a time when capitalist economies were stagnant, and the conditions of working people, and oppressed nationalities especially, were under siege.

Cuba provided a fleet of more than a dozen state of the art fishing boats, transforming Grenada’s 5000-odd tiny and dangerous dingy-like boats into a more efficient operation while cutting down on waste and the need to import food. Previously, much of the caught fish were dried on tin roofs, only to rot when Grenada’s tropical rain ruined much of the catch. Refrigeration facilities were similarly proved by Cuba, which allowed for the preservation of fruits and vegetables. A program to increase the availability of electricity was set into motion on an island where the great majority had none.

Again with the help of the Cubans, medical and dental care became free to all, with the number of doctors, although still far from meeting the needs of the people, dramatically increasing in a few years. Prior to the revolution there was only one dental clinic serving the entire island.

Grenada’s sister islands, Petite Martinique and Carriacou, which together constituted the Grenadian state, had long been stripped bare—their tropical rainforests practically reduced to deserts—and their people given no alternative but to live on remittances from Grenada and abroad. Jobs and healthcare were provided there as well.

In four short years, unemployment was reduced from 49 percent to 14.2 percent. Virtually free loans for construction materials to repair dilapidated housing, the sad living norm for most Grenadians, were provided, while a broad range of infrastructure improvements were undertaken. Roads had barely existed in Grenada; there were only some 48 miles in total before the revolution. A new series of roads were built to aid local farmers in bringing their crops to market. Pipe-borne water, which the great majority had had no previous access to, was significantly expanded, and rusted pipes were repaired.

With help of the Cubans, agriculture was diversified, especially since Grenada, the world largest nutmeg producer, was dependent for income on three export crops—nutmeg, cocoa, and bananas.

Thirty percent of the population was excluded from taxation while the few wealthy hotel owners saw their taxes, which they had barely paid due to an almost total lack of an accounting system regarding hotel revenues, significantly increased. Women’s equality, including equal pay for equal work, was enshrined in Grenadian law, along with extended and paid maternity leave. The law strictly banned all sexual exploitation of women in return for employment.

All of these critical gains notwithstanding, almost everyone understood that Grenada, essentially a huge mountain with poor soil conditions and surrounded by a single road, was currently incapable of putting into effect more dramatic and long lasting improvements. The PRG leadership moved to resolve this dilemma by embarking on the construction of a major international airport, able to provide access to the world’s modern airplanes. With significant loans from Canada and the allocation of vast human resources, again from revolutionary Cuba, Grenadian and Cuban workers began construction on this project aimed at promoting tourism as the major source of income in the years to come. Grenada’s antiquated Pearl Airport was capable of landing only small turboprop planes with a capacity of some 30-50 people.

Perhaps the most controversial debate inside the PRG was the very nature of the system of governance to be established. Early on, the revolution, especially at Bishop’s prodding, established a system of what was called participatory democracy, wherein workers’ and farmers’ councils, parish councils, and zonal councils met to discuss the revolution’s priorities and how they could best be achieved.

While these groups initially met with great enthusiasm and were well attended, in time attendance declined when the participants came to understand that there was a qualitative difference between the participation of the masses, including their right to criticize and recommend important changes, and their right to decide. While the leaders of these councils were often elected and subject to immediate recall, their role remained advisory. Key decisions remained in the hands of the tiny group of the revolution’s main leaders organized in a Central Committee of some dozen individuals.

Bishop was known to advocate increased decision-making power to the local councils. Coard defended maintaining the power and authority of the Central Committee. The size of the organized core of the New Jewel Movement was likely quite small, at best in the hundreds. Even here, however, the NJM rarely, if ever, met as a decision-making body.

I first noted tensions in the PRG when I visited to attend the Nov. 23-25, 1981, First International Conference in Solidarity with Grenada and to deliver a relatively large amount of supplies to support their literacy campaign. Our Bay Area committee was fortunate to link up with a San Francisco GreenPeace group sailing a sizeable ship toward Grenada and agreeable to cramming its hold with tons of supplies. This was for the “welfare of the Grenadians,” they explained, “as well as to provide needed ballast for the ship to insure its safe voyage.”

I was quite surprised to meet Bishop during this conference when he asked for a meeting to discuss a conflict we were experiencing in the Bay Area with the recently formed U.S.-Grenada Friendship Society. Our Grenada Solidarity Committee, formed two years earlier, had established close ties with Grenada’s UN Consul General, Joseph Kanute Burke, who we toured through the Bay Area twice during that time. Yet we were shunned by the Communist Party-initiated U.S.-Grenada Friendship Society as being illegitimate. Through Burke, this had come to the attention of Bishop, who expressed concern that I was not scheduled to address the conference.

Bishop was quite familiar with the Socialist Workers Party. When he resided in Brooklyn, N.Y., where more than 80,000 Grenadian nationals lived, he was an occasional speaker at SWP-sponsored Militant Labor Forums. When the SWP’s 1980 U.S. Presidential candidate, Andrew Pulley, visited Grenada in 1981, he received a surprise visit from Bishop, who humorously asked, “Hey Andrew, what are you doing on my island?” Bishop, driving an old VW Bug, proceeded to give Pulley a personal tour.

During the conference Bishop learned that it was a representative of the U.S. Communist Party that sought to prevent me from greeting the conference. His response was to send his closest ally, Minister of Agriculture George Louison, to resolve this matter in a three-way meeting. Louison sternly explained to the CPer that Grenada valued our work and operated on the principle of non-exclusion. I would speak as the U.S. representative, he insisted, as he urged future collaboration between all Grenada’s supporters.

Bishop’s June 5, 1983, visit to New York has been cited by some as perhaps a source of the divisions that would be revealed some three months later. Some uninformed “left” critics noted that Bishop advocated in his talk improved relations with the United States, including U.S. recognition of a Grenadian ambassador. Here Bishop advocated no more than the Cubans, who had been denied formal recognition for decades. The implication of these “critics” was that Bishop was “soft” on imperialism.” But in explaining the functioning of Grenada’s participatory democracy, Bishop did employ some formulations that could be taken as important, if not critical insights into a sharpening controversy inside the PRG.

Bishop stated: “And for the people in general, there have been organs of popular democracy that have been built—zonal councils, parish councils, worker-parish councils, farmer councils—where the people come together from month to month. The usual agenda will be a report on programs taking place in the village.

“Then there will be a report, usually by some senior member of the bureaucracy. It might be the manager of the Central Water Commission. Or it might be the manager of the telephone company or the electricity company. Or it might be the chief sanitary inspector, or the senior price-control inspector.

“And this senior bureaucrat has to go there and report to the people on his area of work, and then be submitted to a question-and-answer session. And after that, one of the top leaders in our country, one of us will also attend those meetings, and ourselves give a report, and usually there is question-and-answer-time at the end of that also.

“In this way, our people from day to day and week to week, are participating in helping to run the affairs of their country. And this is not just an abstract matter of principle. It has also brought practical, concrete benefits to our people.”

Bishop’s references here to “senior members of the bureaucracy” and “this senior bureaucrat” may not have been accidental, especially in light of his experience in the Central Committee, where a twisted version of “democratic centralism” prevailed—that is, a bureaucratically enforced muzzle banning criticism of “majority” decisions without recourse to democratic discussion and debate in the party’s ranks, not to mention among the increasingly organized masses in the emerging and varied councils.

In truth, there were no “ranks” of the PGR or the NJM that met to decide anything. Power was vested in the hands of a tiny few—the Central Committee. As I have noted, a few months later, Bishop was arrested because he sought to challenge this Coard-led bureaucracy, based on the rule of perhaps a dozen or so leaders. Vesting real power in the various councils that had been established was not on Coard’s agenda.

Although no formal records exist of its decisions, the debates in the tiny Central Committee were “resolved” in Coard’s favor, and Bishop, while retaining the title of prime minister, saw his authority much diminished. He was soon afterwards sent to Czechoslovakia on a trade mission and returned to Grenada via Cuba. Upon his return he was reported to have informed the Central Committee of his intention to challenge their orientation, whereupon he was immediately placed under “house arrest,” incarcerated, and placed under armed guard in his own house at Mount Wheldale, literally across the road from Coard’s dwelling.

When news of Bishop’s arrest reached his closest associates, Minister of Agriculture George Louison, accompanied by Bishop’s press secretary, Don Rojas, quickly organized a mass march to Bishop’s home to free the island’s most well-known and popular leader—“Bish,” as he was called by friends everywhere. The march to liberate Bishop and its arrival at his home was observed first hand by a member of our San Francisco Bay Area Grenada Solidarity Committee, who we had sent to assist with Grenada’s literacy program. This mass mobilization rapidly grew until tens of thousands participated. Bishop was freed with zero resistance and immediately proceeded to lead the marchers to Fort Rupert, Grenada’s military headquarters in the capital city, St. Georges, and Coard’s likely location.

Bishop led the angry marchers onto this ancient stonewalled fort’s patio, whereupon he and his associates were gunned down at the orders of Coard’s appointed “General,” Hudson Austin. Three ministers were murdered outright—including Bishop and his companion and Minister of Education Jacqueline Creft—and two leading trade unionists. As Coard’s tiny death squad fired on the crowd, killing perhaps a dozen or more, others leaped to safety from the fort’s great walls, suffering serious injuries or death. The wounded and injured were treated by medical teams that included members of the Swedish section of the Fourth International.

The Grenadian Revolution ended that day. The U.S. invasion that followed a few days later was met with virtually no resistance except for the several hundred Cuban airport workers. Breaking a formal agreement that had been hurriedly negotiated between the Cuban government and the Reagan administration, affirming that the Cubans would not resist the invasion and would act only in self defense, the Rangers nevertheless opened fire on the Cubans, who alone courageously resisted as well as they could the massive power of the imperialist forces.

Several hundred Cubans were arrested and jailed but soon afterward released to return home. There was virtually zero resistance from Grenada’s armed forces or militias. Fearing mass hatred for his action in imprisoning Bishop, Coard invoked martial law and enforced strict curfews. Weapons were locked tight in Grenada’s armories. The island was “conquered” by the invaders in a matter of hours as Grenada’s humiliated and demoralized masses were rendered helpless and disarmed.

All the pretexts employed by the Reagan administration and the capitalist media were soon repudiated. There were many—all lies. Grenada was said to be threatening the lives of some 700 U.S. medical students on the island; Grenada was said to be constructing a military base for Soviet use on its new airport; Grenada was said to be detaining political prisoners; Reagan officials even implied that Cuba had orchestrated the coup and was behind the murder of Bishop and his comrades. And finally, the U.S. claimed to have been invited to invade by the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States.

These lies were broadcast around the world without regard to their veracity. The invasion was repudiated almost everywhere, including by an overwhelming vote of the UN General Assembly. Cuban President Fidel Castro condemned the coup. Coard and his associates were labeled Stalinists and traitors to the revolution. An official day of mourning was organized in Cuba to commemorate Bishop’s achievements. Cables from Cuba threatened to cut off all aid to the Coard regime.

Before this Cuban condemnation and immediately after Bishop’s murder, the SWP leadership stood publicly mute. But it soon became clear that central party leaders were more than prepared to side with “the Central Committee majority.” Following Bishop’s arrest I had been in daily contact with Consul General Joseph Kanute Burke, who in turn was in daily contact with Bishop’s mother, who had been allowed to visit her son to bring him food.

Burke reported that “the boys” were talking, and that a resolution was possible in his view. History demonstrates that this never came to pass. The SWP demanded that I cease all contact with Burke and Grenada. They went further; the Oakland/Berkeley party organizer insisted that I unilaterally cancel the planned demonstration set for the San Francisco Federal Building the following day, a decision that had been unanimously taken by the ranks of the Grenada Solidarity Committee, with 100 activists present!

“Do you know” the party organizer asked me, “that Bishop was in the minority of the Central Committee?” I responded, “I am in the minority of the SWP. Do you intend to murder me?” Ignoring this, the organizer demanded that I tell her what I would say about Bishop’s assassination. “I will oppose it,” I replied, adding, “We do not resolve internal disputes by murder.” The veneer of civility, not to mention comradely discussions, disappeared forever in that exchange. I spent the next several hours preparing the final details for the protest and resigned from the SWP the next day.

In my view, two parties had died that terrible day, both having irrevocably lost their revolutionary integrity. The degeneration of both had been long in the making. The history of the SWP’s degeneration has yet to be written. The few feeble attempts to date miss the mark entirely.

Grenada’s Revolution set out to be an example to the world as to what Black Power and the fight for socialism could mean. Its heroic figure, Maurice Bishop, will not be forgotten. We honor his memory in this 30th year marking his brutal murder at the hands of a Stalinist thug.

No comments:

Post a Comment